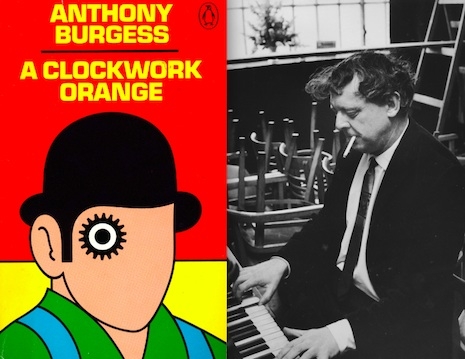

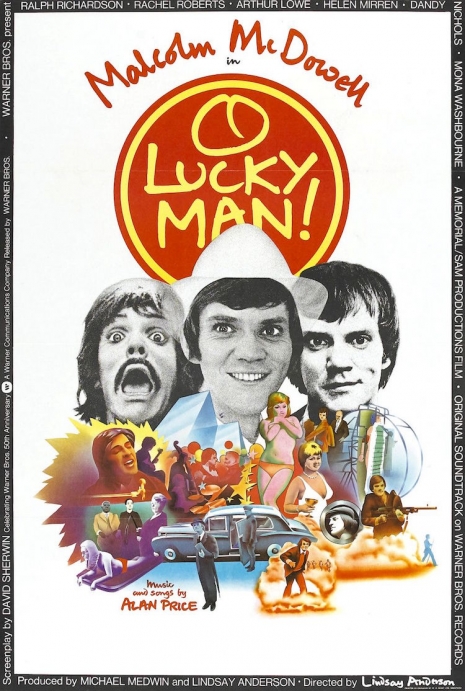

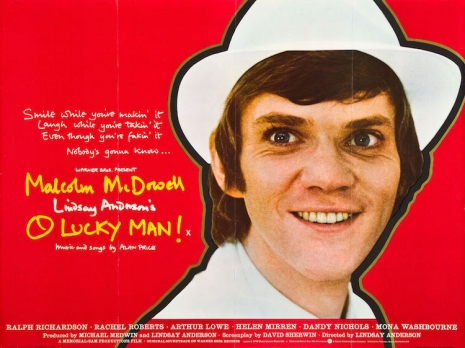

The argument at the back of the bar was about which decade produced the best films. The noughties didn’t make it, nor did the teens, unless that was the nineteen-teens. The shortlist was whittled down and we agreed upon the forties, the fifties, the sixties, but were almost unanimous on the seventies. That glorious decade when movies had something important to say as told by actors, writers, and directors and not CGI. The decade that gave us Taxi Driver, The Godfather, The French Connection, Deliverance, Apocalypse Now, Mean Streets, The Conversation, The Exorcist, The Last Detail, Chinatown, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Don’t Look Now, Tommy, Roma, Jubilee, Star Wars, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Jaws, A Clockwork Orange, and a marathon-length movie like Lindsay Anderson’s O Lucky Man! among many, many other cinematic classics.

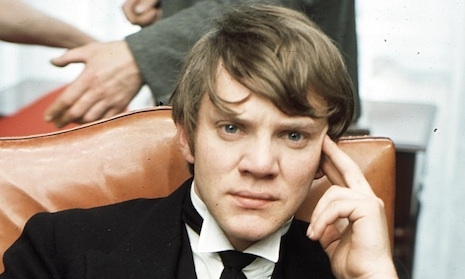

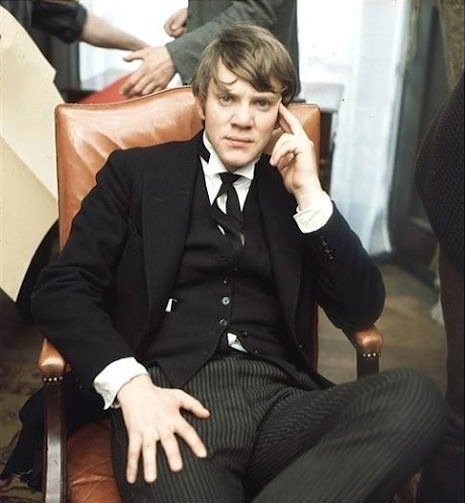

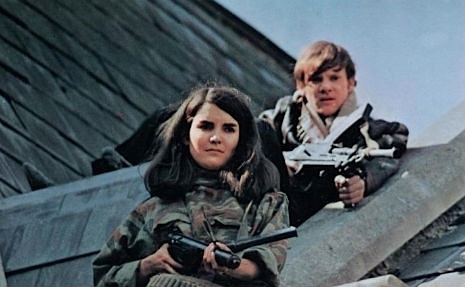

Malcolm McDowell had the original idea for O Lucky Man! He wanted to work again with director Lindsay Anderson after their success on the class war fantasy If… in 1968. McDowell had an idea for a film based around his own experiences working as a coffee salesman. In August 1970, twenty pages were written in collaboration with If… screenwriter David Sherwin. These were then shown to Anderson, who thought the story of a coffee salesman being mistaken for a spy “too mini and naturalistic.” Nevertheless, he encouraged McDowell and Sherwin to keep on working and get it away from “just being about selling coffee.” Anderson wanted something “epic” and suggested they read Heaven’s My Destination about a bible salesman, Franz Kafka’s Amerika, and Voltaire’s Candide.

On August 21st 1970, Sherwin was at McDowell’s flat talking ideas back-and-forth “trying to find the essence of [their twenty-page script] Coffee Man, trying to make it ‘epic’ for Lindsay,” as Sherwin noted in his diary.

McDowell recalled the Sales Director, Gloria Rowe, who he often talked to when training on the shop floor.

“I wasn’t really training—I was just walking around with a clipboard looking for something to do—she used to say to me, ‘Malcolm, you’ll either end up a duke or a dustman.’ And I’d always been told I was born with a silver spoon in my mouth. I always believed I would be lucky.”

Sherwin jumped up and said “That’s it!”

“What?” said McDowell.

“Luck—luck’s the essence. You’ve always believed you’ll be lucky.”

“Yes—luck—Lucky Man.”

“Lucky Man!” they yelled in unison.

Now they had a title and the essence of what they hoped would be their next film. They drove round to tell Anderson.

“We’ve got the title, Lindsay, Lucky Man.”

Anderson made the inside of his cheek pop with his forefinger—“an annoying habit” he had when considering the merit of something. He then said, “No.” And gave pause for full dramatic effect before adding it should be O Lucky Man, like [one of his earlier films], O Dreamland or even the stage show Oh! Calcutta. The title should also have an exclamation mark—but where to put it?

“After the ‘O’?” ventured Sherwin.

‘No,” said Anderson, “At the end.”

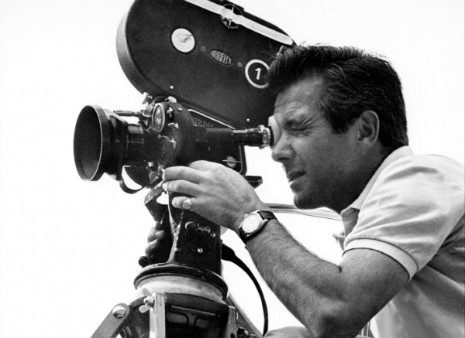

Anderson always had the demeanor of one who knows best. The tetchy grown-up lecturing the kids. It was an artifice he used to hide his own insecurities, his lack of confidence, and to repress his sexuality. His personality became, as the actor Alan Bates noted, abrasive which irked critics and producers alike and eventually “lost him the opportunity to make more films.” Bates was similarly closeted about his own homosexuality—never acknowledging his gay lovers or admitting his sexual orientation. Anderson was born into a military family in Bangalore, India, in 1923. His parents separated and his father cut his family out of his life, an experience which made Anderson distrustful of sharing his emotions. After university and military service in the Second World War, Anderson had considered becoming an actor before focussing on a career as a film critic and then film and stage director. In 1956, he co-founded the Free Cinema movement with Karel Reisz, Tony Richardson and Lorenza Mazzetti. Their belief was that “no film could be too personal.” That the image was more important than sound and “a belief in freedom, in the importance of people and the significance of the everyday.”

Though Anderson spent more time working in theater, he still managed to make an impressive catalog of innovative and highly controversial films like O Dreamland, This Sporting Life, If…, O Lucky Man! and Britannia Hospital.

Full photo-spread for ‘O Lucky Man!,’ after the jump…