This is the transcript of a discussion that took place earlier this year between Noam Chomsky and Occupy supporters Mikal Kamil and Ian Escuela for InterOccupy, an organisation that provides links between supporters of the Occupy movement around the world.

Professor Chomsky, the Occupy movement is in its second phase. Three of our main goals are to: 1) occupy the mainstream and transition from the tents and into the hearts and the minds of the masses; 2) block the repression of the movement by protecting the right of the 99%‘s freedom of assembly and right to speak without being violently attacked; and 3) end corporate personhood. The three goals overlap and are interdependent.

We are interested in learning what your position is on mainstream filtering, the repression of civil liberties, and the role of money and politics as they relate to Occupy and the future of America.

Noam Chomsky: Coverage of Occupy has been mixed. At first it was dismissive, making fun of people involved as if they were just silly kids playing games and so on. But coverage changed. In fact, one of the really remarkable and almost spectacular successes of the Occupy movement is that it has simply changed the entire framework of discussion of many issues. There were things that were sort of known, but in the margins, hidden, which are now right up front – such as the imagery of the 99% and 1%; and the dramatic facts of sharply rising inequality over the past roughly 30 years, with wealth being concentrated in actually a small fraction of 1% of the population.

For the majority, real incomes have pretty much stagnated, sometimes declined. Benefits have also declined and work hours have gone up, and so on. It’s not third world misery, but it’s not what it ought to be in a rich society, the richest in the world, in fact, with plenty of wealth around, which people can see, just not in their pockets.

All of this has now been brought to the fore. You can say that it’s now almost a standard framework of discussion. Even the terminology is accepted. That’s a big shift.

Earlier this month, the Pew foundation released one of its annual polls surveying what people think is the greatest source of tension and conflict in American life. For the first time ever, concern over income inequality was way at the top. It’s not that the poll measured income inequality itself, but the degree to which public recognition, comprehension and understanding of the issue has gone up. That’s a tribute to the Occupy movement, which put this strikingly critical fact of modern life on the agenda so that people who may have known of it from their own personal experience see that they are not alone, that this is all of us. In fact, the US is off the spectrum on this. The inequalities have risen to historically unprecedented heights. In the words of the report: “The Occupy Wall Street movement no longer occupies Wall Street, but the issue of class conflict has captured a growing share of the national consciousness. A new Pew Research Center survey of 2,048 adults finds that about two-thirds of the public (66%) believes there are “very strong” or “strong” conflicts between the rich and the poor – an increase of 19 percentage points since 2009.”

Meanwhile, coverage of the Occupy movement itself has been varied. In some places – for example, parts of the business press – there has been fairly sympathetic coverage occasionally. Of course, the general picture has been: “Why don’t they go home and let us get on with our work?” “Where is their political programme?” “How do they fit into the mainstream structure of how things are supposed to change?” And so on.

And then came the repression, which of course was inevitable. It was pretty clearly coordinated across the country. Some of it was brutal, other places less so, and there has been kind of a stand-off. Some occupations have, in effect, been removed. Others have filtered back in some other form. Some of the things have been covered, like the use of pepper spray, and so on. But a lot of it, again, is just, “Why don’t they go away and leave us alone?” That’s to be anticipated.

The question of how to respond to it – the primary way is one of the points that you made: reaching out to bring into the general Occupation, in a metaphorical sense, to bring in much wider sectors of the population. There is a lot of sympathy for the goals and aims of the Occupy movement. They are quite high in polls, in fact. But that’s a big step short from engaging people in it. It has to become part of their lives, something they think they can do something about. So it’s necessary to get out to where people live. That means not just sending a message, but if possible, and it would be hard, to try to spread and deepen one of the real achievements of the movement that doesn’t get discussed much in the media – at least, I haven’t seen it. One of the main achievements has been to create communities – real functioning communities of mutual support, democratic interchange, care for one another, and so on. This is highly significant, especially in a society like ours in which people tend to be very isolated and neighbourhoods are broken down, community structures have broken down, people are kind of alone.

There’s an ideology that takes a lot of effort to implant: it’s so inhuman that it’s hard to get into people’s heads, the ideology to just take care of yourself and forget about anyone else. An extreme version is the Ayn Rand version. Actually, there has been an effort for 150 years, literally, to try to impose that way of thinking on people.

During the onset of the industrial revolution in eastern Massachusetts, mid-19th century, there happened to be a very lively press run by working people, young women in the factories, artisans in the mills, and so on. They had their own press that was very interesting, very widely read and had a lot of support. And they bitterly condemned the way the industrial system was taking away their freedom and liberty and imposing on them rigid hierarchical structures that they didn’t want. One of their main complaints was what they called “the new spirit of the age: gain wealth forgetting all but self”. For 150 years there have been massive efforts to try to impose “the new spirit of the age” on people. But it’s so inhuman that there’s a lot of resistance, and it continues.

One of the real achievements of the Occupy movement, I think, has been to develop a real manifestation of rejection of this in a very striking way. The people involved are not in it for themselves. They’re in it for one another, for the broader society and for future generations. The bonds and associations being formed, if they can persist and if they can be brought into the wider community, would be the real defence against the inevitable repression with its sometimes violent manifestations.

How best do you think the Occupy movement should go about engaging in these, what methods should be employed, and do you think it would be prudent to actually have space to decentralise bases of operation?

Noam Chomsky: It would certainly make sense to have spaces, whether they should be open public spaces or not. To what extent they should be is a kind of a tactical decision that has to be made on the basis of a close evaluation of circumstances, the degree of support, the degree of opposition. They’re different for different places, and I don’t know of any general statement.

As for methods, people in this country have problems and concerns, and if they can be helped to feel that these problems and concerns are part of a broader movement of people who support them and who they support, well then it can take off. There is no single way of doing it. There is no one answer.

You might go into a neighbourhood and find that their concerns may be as simple as a traffic light on the street where kids cross to go to school. Or maybe their concerns are to prevent people from being tossed out of their homes on foreclosures.

Or maybe it’s to try to develop community-based enterprises, which are not at all inconceivable – enterprises owned and managed by the workforce and the community which can then overcome the choice of some remote multinational and board of directors made out of banks to shift production somewhere else. These are real, very live issues happening all the time. And it can be done. Actually, a lot of it is being done in scattered ways.

A whole range of other things can be done, such as addressing police brutality and civic corruption. The reconstruction of media so that it comes right out of the communities, is perfectly possible. People can have a live media system that’s community-based, ethnic-based, labour-based and [reflecting] other groupings. All of that can be done. It takes work and it can bring people together.

Actually, I’ve seen things done in various places that are models of what could be followed. I’ll give you an example. I happened to be in Brazil a couple of years ago and I was spending some time with Lula, the former president of Brazil, but this was before he was elected president. He was a labour activist. We travelled around together. One day he took me out to a suburb of Rio. The suburbs of Brazil are where most of the poor people live.

They have semi-tropical weather there, and the evening Lula took me out there were a lot of people in the public square. Around 9pm, prime TV time, a small group of media professionals from the town had set up a truck in the middle of the square. Their truck had a TV screen above it that presented skits and plays written and acted by people in the community. Some of them were for fun, but others addressed serious issues such as debt and Aids. As people gathered in the square, the actors walked around with microphones asking people to comment on the material that had been presented. They were filmed commenting and were shown on the screen for other people to see it.

People sitting in a small bar nearby or walking in the streets began reacting, and in no time you had interesting interchanges and discussions among people about quite serious topics, topics that are part of their lives.

Well, if it can be done in a poor Brazilian slum, we can certainly do it in many other places. I’m not suggesting we do just that, but these are the kinds of things that can be done to engage broader sectors and give people a reason to feel that they can be a part of the formation of communities and the development of serious programmes adapted to whatever the serious needs happen to be.

From very simple things up to starting a new socio-economic system with worker- and community-run enterprises, a whole range of things is possible. The more active public support there is the better defence there is against repression and violence.

How do you assess the goals of the Democratic party as far as co-opting the movement, and what should we be vigilant and looking out for?

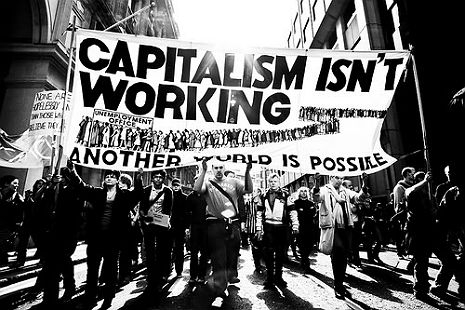

Noam Chomsky: The Republican party abandoned the pretence of being a political party years ago. They are committed, so uniformly and with such dedication, to tiny sectors of power and profit that they’re hardly a political party any more. They have a catechism they have to repeat like a caricature of the old Communist party. They have to do something to get a voting constituency. Of course, they can’t get it from the 1%, to use the imagery, so they have been mobilising sectors of the population that were always there, but not politically organised very well – religious evangelicals, nativists who are terrified that their rights and country are being taken away, and so on.

The Democrats are a little bit different and have different constituencies, but they are following pretty much the same path as the Republicans. The centrist Democrats of today, the ones who essentially run the party, are pretty much the moderate Republicans of a generation ago and they are now kind of the mainstream of the Democrat party. They are going to try to organise and mobilise – co-opt, if you like – the constituency that’s in their interest. They have pretty much abandoned the white working-class; it’s rather striking to see. So that’s barely part of their constituency at this point, which is a pretty sad development. They will try to mobilise Hispanics, blacks and progressives. They’ll try to reach out to the Occupy movement.

Organised labour is still part of the Democratic constituency and they’ll try to co-opt them; and with Occupy, it’s just the same as all the others. The political leadership will pat them on the head and say: “I’m for you, vote for me.” The people involved will have to understand that maybe they’ll do something for you, that only if you maintain substantial pressure can you get elected leadership to do things – but they are not going to do it on their own, with very rare exceptions.

As far as money and politics are concerned, it’s hard to beat the comment of the great political financier Mark Hanna. About a century ago, he was asked what was important in politics. He answered: “The first is money, the second one is money and I’ve forgotten what the third one is.”

That was a century ago. Today it’s much more extreme. So yes, concentrated wealth will, of course, try to use its wealth and power to take over the political system as much as possible, and to run it and do what it wants, etc. The public has to find ways to struggle against that.

Centuries ago, political theorists such as David Hume, in one of his foundations for government, pointed out correctly that power is in the hands of the governed and not the governors. This is true for a feudal society, a military state or a parliamentary democracy. Power is in the hands of the governed. The only way the rulers can overcome that is by control of opinions and attitudes.

Hume was right in the mid-18th century. What he said remains true today. The power is in the hands of the general population. There are massive efforts to control it by less force today because of the many rights that have been won. Methods now are by propaganda, consumerism, stirring up ethnic hatred, all kinds of ways. Sure, that will always go on but we have to find ways to resist it.

There is nothing wrong with giving tentative support to a particular candidate as long as that person is doing what you want. But it would be a more democratic society if we could also recall them without a huge effort. There are other ways of pressuring candidates. There is a fine line between doing that and being co-opted, mobilised to serve someone else’s interest. But those are just constant decisions and choices that have to be made.

Extracted from Occupy by Noam Chomsky, published by the Zuccotti Park Press and the Occupied Media Pamphlet Series in the US and Canada.