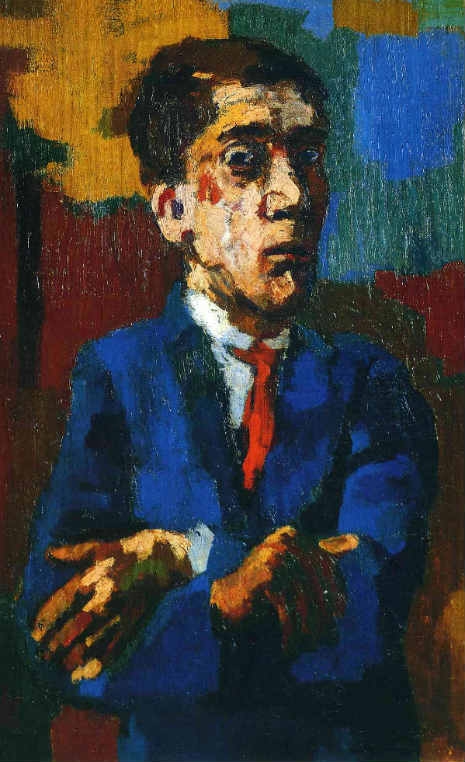

Artist Oskar Kokoschka and his muse Alma Mahler.

The work of Austrian artist Oskar Kokoschka was hugely influential in the world of Expressionism. Fiercely opposed to the Nazis, Kokoschka also produced work for the visual art collective Wiener Werkstätte as well as other designs and stage productions for the Art Nouveau-themed Cabaret Fledermaus. His ability to infuse a sense of dread and trepidation into his paintings and other creations would end up earning him the moniker of “Chief Savage.” Nearly entirely self-taught, Kokoschka did attend the Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts), though he almost didn’t graduate. Luckily architect Adolf Loos became aware of Kokoschka’s work and helped to further develop the artist’s proficiency for painting. In 1909 at the age of 23, Kokoschka would paint Loos and the finished product has been noted as one of his greatest works of portraiture. As important as Kokoschka’s contributions to Expressionism are, it would be his torrid love affair with Alma Mahler which led to the production of some of his most contentious work, as well as an emotional meltdown of epic proportions.

Kokoschka began his relationship with Mahler (the widow of composer Gustav Mahler) in 1912. Kokoschka was completely enamored with Mahler, and he spent every moment with her. He drew and painted her image to the point of obsession for the three short years they spent together becoming his primary, if not solitary, muse. As you might imagine, things got a bit too heavy for Mahler and she left the possessive artist. The breakup sent Kokoschka into a dire downward spiral during which he enlisted as an Austrian cavalryman in WWI in 1915. During his time in the military, he was critically injured after taking a bullet to the head and suffering the effects of shell shock—sending him off to recover in a hospital in Dresden on at least two occasions. During his second stay in Dresden, his doctors found Kokoschka to be exhibiting signs of “mental instability” and would keep him around for a few years until they were sure he had fully recovered.

“The bride of the wind” a self-portrait by Oskar Kokoschka with his love and muse Alma Mahler in 1913.

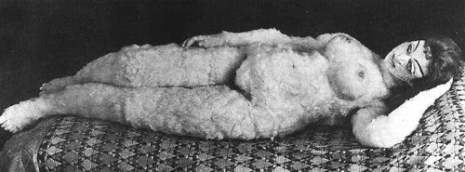

Once he received a clean bill of health, Kokoschka returned to Austria in 1918 and commissioned the services of Hermine Moos, a German dollmaker and artist, requesting she make a life-sized doll in the image of his ex-girlfriend, Alma Mahler. During their working relationship, Kokoschka would deluge Moos with excruciatingly detailed letters regarding his various “requirements” for the doll. Here’s one Kokoschka sent to Moos dated August 20th, 1918 which will help further illuminate the artist’s fixation with Mahler. You might want to take a seat for this one:

Yesterday I sent a life-size drawing of my beloved, and I ask you to copy this most carefully and to transform it into reality. Pay special attention to the dimensions of the head and neck, to the ribcage, the rump, and the limbs. And take to heart the contours of the body, e.g., the line of the neck to the back, the curve of the belly. Please permit my sense of touch to take pleasure in those places where layers of fat or muscle suddenly give way to a sinewy covering of skin. For the first layer (inside), please use fine, curly horsehair; you must buy an old sofa or something similar; have the horsehair disinfected. Then, over that, a layer of pouches stuffed with down, cottonwool for the seat and breasts. The point of all this for me is an experience which I must be able to embrace!”

In another disturbing letter to Moos dated December 20, 1918, Kokoschka feverishly inquired if the doll’s mouth would be able to be “opened” and if so, would there be “teeth and a tongue inside.” Once the doll finally arrived, things got decidedly more bizarre. Kokoschka enlisted the help of his servants to spread rumors that the doll version of Mahler was a real woman. He would ride around with her in his carriage and brought her to the opera. And like the real Mahler, he painted her picture over and over again—perhaps 80 times. While the doll did a good job at being a compliant subject and companion, it was no substitute for the real thing. Eventually, Kokoschka realized he was finally over Mahler and threw a party to celebrate the occasion. One of Kokoschka’s servants dressed the doll up in her best party clothes and perched her on a chair in the midst of the revelers. According to Kokoschka, he was pretty loaded, and as he and his fellow drunks watched the sunrise he decided to drag the doll out into his garden, pour a bottle of red wine over it, and chop off its head with an axe. No big deal.

Kokoschka left the decapitated doll in his yard and went to bed to sleep things off. Early the next morning a police officer happened to catch a glance of what he believed to be the headless, bloody body of a nude woman in Kokoschka’s yard. He called for backup and the cops busted through his front door fully expecting to find a crime scene. At this point, you might be thinking this is how Kokoschka ended up with a one-way ticket to the loony bin—but nothing could be further from the truth. In addition to marrying a real girl, he would continue to paint and exhibit his work in museums all over the world, such as the MFA in Boston in 1948, and MoMA in New York in 1949. After a long, prosperous career, Kokoschka passed away at the age of 94 in the Swiss municipality of Montreux. Lastly, if you’re wondering if this might be the first recorded instance of someone acquiring a made-to-order sex doll, it isn’t. If my research is correct, the first dolls used for sex were apparently made by Dutch sailors during the 1700s. The dolls—which were made from leather—were called “dama de viaje” or “travel lady.” And now you know!

The images that follow are NSFW.

More after the jump…