Pauline Boty was an artist, activist, actress and model. She was one of the leading figures of the British Pop art movement during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Her contemporaries were Peter Blake, Derek Boshier and David Hockney. But when Boty tragically died at the height of her fame in 1966, her work mysteriously disappeared. Not one of her paintings was exhibited again until 1993.

Boty was all but forgotten by the time a cache of her paintings was rediscovered on a farm in the English countryside in the early 1990s. The paintings had been stored in an old barn for safe-keeping by her brother. Their rediscovery placed Boty firmly back into the center of the Pop art boy’s club.

Throughout her life, Boty kicked against the men who tried to hold her back. Born into a Catholic family in 1938, her father (a by-the-book accountant) wanted his daughter to marry someone respectable and raise a family. Instead she chose to study art to her father’s great displeasure. In 1954, Boty won a scholarship to Wimbledon School of Art.

At college, Boty was dubbed the “Wimbledon Bridget Bardot” because of her blonde hair and film star looks. She went onto study lithography and stained glass design. However, her desire was to study painting. When she applied to the Royal College of Art in 1958, it was suggested by the male tutors that she would be more suited studying stained glass design as there were so few women painters. Though Boty enrolled in the design course she continued with her ambitions to paint.

Encouraged by the original Pop artist Eduardo Paolozzi, Boty began painting at her apartment. Her makeshift studio soon became a meeting point for her friends (Derek Marlowe, Celia Birtwell) and contemporaries (Blake, Boshier, Hockney and co) to meet, talk and work. Boty started exhibiting her collages and paintings alongside these artists and her career as a painter commenced.

In 1962, Boty was featured in a documentary about young British pop artists Pop Goes the Easel alongside Peter Blake, Derek Boshier and Peter Phillips. The film was directed by Ken Russell who created an incredibly imaginative and memorable portrait of the four artists. Each was given the opportunity to discuss their work—only Boty did not. Instead she collaborated with Russell on a very prescient dream sequence.

It opens with Boty laying out her paintings and drawings on the floor of a long circular corridor—actually the old BBC TV Center. As she examines her work a group of young women appear behind her. These women walk all over her artwork. Then from out of an office door, a nightmarish figure in a wheelchair appears and chases Boty along the seemingly endless twisting corridors. Boty eventually escapes into an elevator—only to find the ominous figure waiting inside.

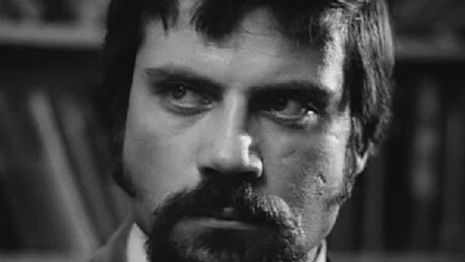

Her performance in Russell’s film led to further acting roles—in Alfie with Michael Caine, with James Fox on the stage, Stanley Baxter on television and again with Russell in a small role opposite Oliver Reed in Dante’s Inferno. Boty was photographed by David Bailey, modeled for Vogue, regularly appeared as an audience dancer on Ready, Steady, Go!, and held legendary parties at her studio to which everyone who was anyone attended—from the Stones to Bob Dylan. Boty was the bright flame to whom everyone was attracted.

She was a feminist icon—living her life, doing what she wanted to do, and not letting men from hold her back. But the sixties were not always the liberated decade many Boomers would have us believe. Boty’s critics nastily dismissed her as the Pop art pin-up girl. The left-wing party girl. A dumb blonde. Of course, they were wrong—but shit unfortunately sticks.

Boty’s work became more politically nuanced. She criticised America’s foreign policy in Vietnam; dissected the unacknowledged sexism of everyday life; and celebrated female sexuality. She had a long affair with the director Philip Saville—which allegedly inspired Joseph Losey’s film Darling with Dirk Bogarde and Julie Christie. Then after a ten day “whirlwind romance” Boty married Clive Goodwin—a literary agent and activist. She claimed he was the only man who was interested in her mind.

In 1965, Boty was nearing the top of her field when she found she was pregnant. During a routine prenatal examination, doctors discovered a malignant tumor. Boty refused an abortion. She also refused chemotherapy as she did not want to damage the fetus. In February 1966, Boty gave birth to a daughter—Boty Goodwin. Five months later in July 1966, Pauline Boty died. Her last painting was a commission for Kenneth Tynan’s nude revue Oh! Calcutta! called “BUM.”

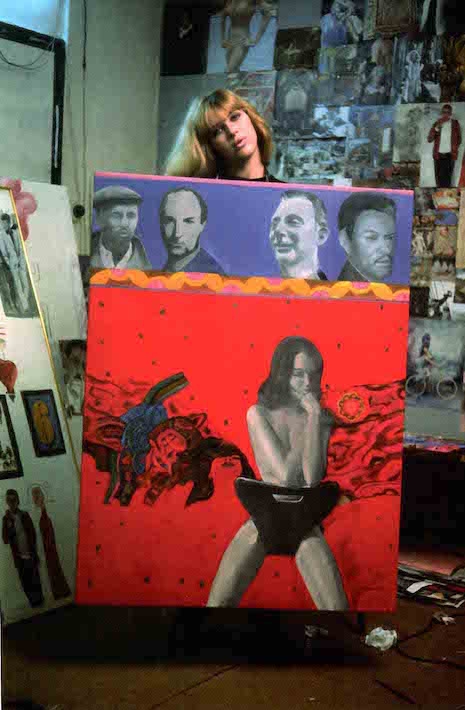

Pauline Boty in her studio holding the painting ‘Scandal’ in 1963.

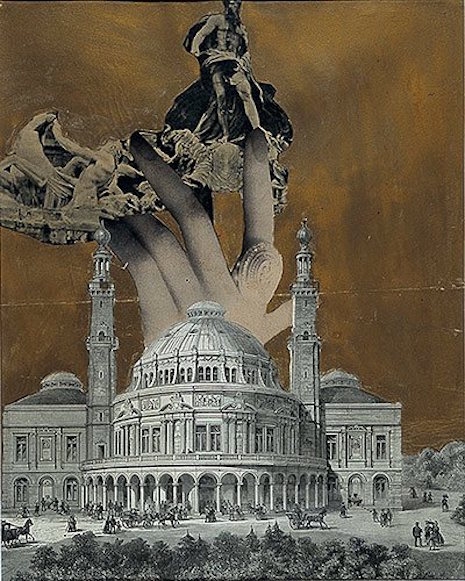

‘A Big Hand’ (1960).

More of Pauline Boty’s paintings plus Ken Russell’s ‘Pop Goes the Easel,’ after the jump…