John Fowles was a 37-year-old school teacher when his first novel The Collector was published in 1963. Though Fowles had been writing for fifteen years completing two novels and an early draft of his second book The Magus, he considered himself “unpublishable.” Then he started work on a dark and disturbing tale about a man who kidnaps a young art student and keeps her imprisoned in the basement of his home. Fowles wrote the book in about a month, and thinking he had nothing to lose sent the manuscript off to his agent, Michael S. Howard who liked it and passed it on to the publishers Jonathan Cape. Tom Maschler at Cape thought The Collector a powerful and impressive debut, but was concerned that Fowles (who thought of himself a “serious writer”) may damage his reputation with such a lurid and disturbing tale. Fowles was adamant—he wanted the book published under his own name.

Anyone familiar with The Collector may have wondered what inspired Fowles’ twisted tale. In a letter written to Maschler in July 1962, the author explained his sources when writing the novel:

...all this came from a newspaper incident of some years ago (there was a similar case in the North of England last year, by the way). But the whole idea of the woman-in-the-dungeon has interested me since I saw Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle, which was before the air-raid shelter case.

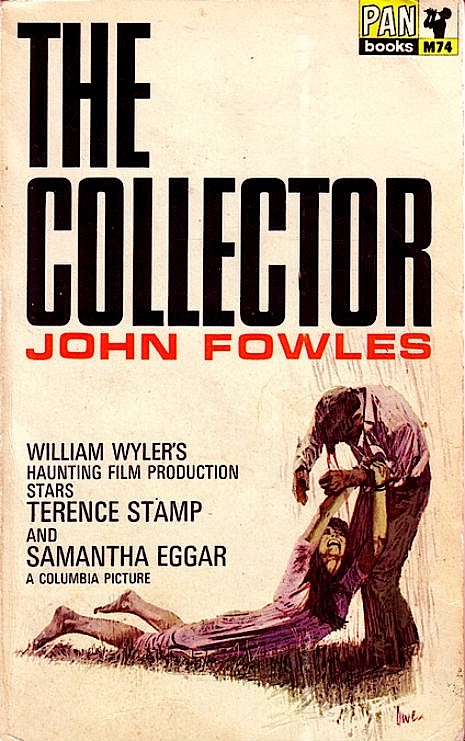

Film poster for ‘The Collector’ starring Terence Stamp and Samantha Eggar, 1965.

The news story Fowles mentioned concerned “a man who had kidnapped a girl and imprisoned her for several weeks in an air-raid shelter at the bottom of his garden.”

While the musical reference Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle (1911) told the story of Duke Bluebeard who warns his new bride Judith not to open any of the seven doors in his castle. Impelled by curiosity, Judith opens each of the seven doors finding behind the first a torture chamber and behind the last, the ghosts of Bluebeard’s previous wives.

Terence Stamp as butterfly collector Frederick Clegg.

However, there was far darker, more personal and deeply troubling inspiration for the novel, which Fowles explained in his journal entry for February 3rd, 1963:

The Collector. The three sources.

One. My lifelong fantasy of imprisoning a girl underground.

I think I must go back to early in my teens. I remember it used to be famous people Princess Margaret, various film stars. Of course, there was a sexual motive; the love-through-knowledge motive, or motif, has also been constant. The imprisoning in other words, has always been a forcing of my personality as well as my penis on the girl concerned.

Variations I can recall: the harem (several girls in one room, or in a row of rooms); the threat (this involves sharing a whip, but usually not flagellation—the idea of exerted tyranny, entering as executioner); the fellow-prisoner (this by far the commonest variation: the girl is captured and put naked into the underground room; I then have myself put in it, as if I am a fellow-prisoner, and so avoid her hostility).

Another common sexual fantasy is the selection board: I am given six hundred girls to choose fifty from and so on. These fantasies have long been exteriorized in my mind, of course; certainly I use the underground-room one far less since The Collector.

Two, the air-raid shelter incident.

Three, Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle.

Samantha Eggar as art student Miranda Grey.

Fowles separated The Collector into three sections, where the captor (Frederick Clegg) and his prisoner (Miranda Grey) describe the events of the book. It begins with Clegg describing the subject of his obsession:

When she was home from her boarding-school I used to see her almost every day sometimes, because their house was right opposite the Town Hall Annexe. She and her younger sister used to go in and out a lot, often with young men, which of course I didn’t like, When I had a free moment from the files and ledgers I stood by the window and used to look down over the road over the frosting and sometimes I’d see her. In the evening I marked it in my observations diary, at first with X, and then when I knew her name with M. I saw her several times outside too. I stood right behind her once in queue at the public library down Crossfield Street. She didn’t look once at me, but I watched the back of her head and her hair in a long pigtail. It was very pale, silky, like burnet cocoons. All in one pigtail coming down almost to her waist, sometimes in front, sometimes at back. Sometimes she wore it up. Only once, before she came to be my guest here, did I have the privilege to see her with it loose, and it took my breath away it was so beautiful, like a mermaid.

Clegg (Stamp) and Miranda (Egggar) in William Wyler’s film version of ‘The Collector.’

Fowles’ intention was not just to write a horror story, but to use the characters of Clegg and Miranda as conduits for his own analysis and critique of modern society, in particular his contempt for the lack of intellectual rigor in contemporary fiction—the Angry Young Men who had so forcefully invaded with John Osborne’s play Look Back in Anger—and for the failure of socialism to bring equality and change to Britain:

The plot of the novel was:

1. present a character who was inarticulate and nasty, as opposed to the “good” inarticulate hero, who seems to be top dog in post-war fiction and whose inarticulateness is presented as a kind of crowning glory.

2. present a character who is articulate and intelligent—the kind of young person I try to make Miranda Grey—and who is quite clearly a better person because she has a better education.

3. attack the money-minus-morality society (the affluent, the acquisitive) we have lived in since 1951.

On its publication, The Collector was a best-seller. The paperback rights were optioned for “probably the highest price that had hitherto been paid for a first novel”. The film rights were sold and a movie starring Terence Stamp and Samantha Eggar was made in Hollywood and London directed by William Wyler.

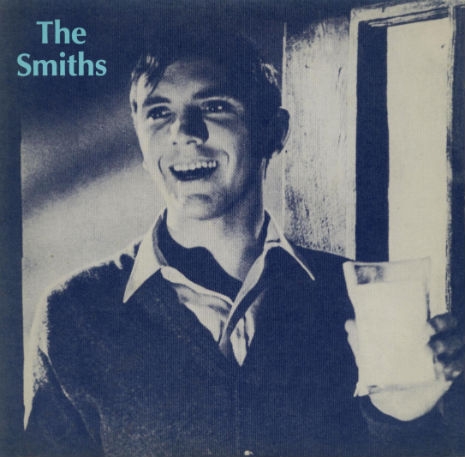

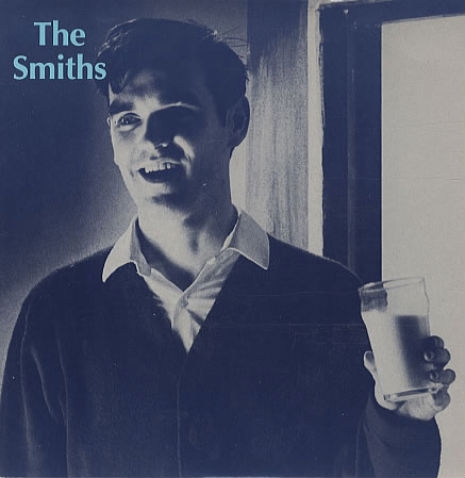

In 1984, The Smiths used a still of Terence Stamp as Clegg from The Collector on the cover of their single “What Difference Does It Make?” As the actor had not given permission for the image to be used, the single was quickly reissued with Morrissey copying Stamp’s original pose—though a glass of milk had replaced the chloroform. Stamp later relented to his image being used.

Terence Stamp as Clegg on the cover of The Smiths single ‘What Difference Does It Make?’

Morrissey as Clegg on the reissued single.