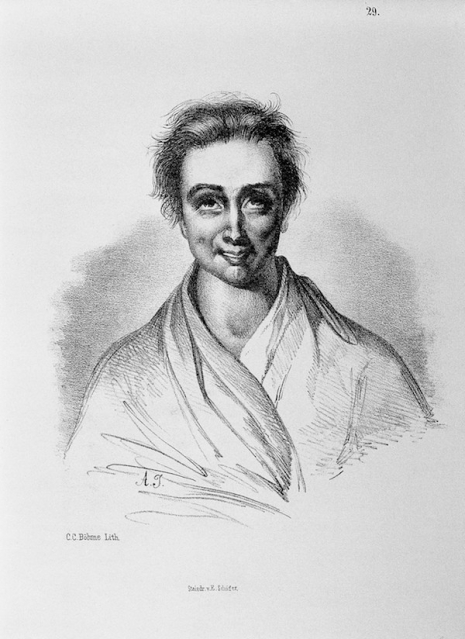

“Female patient suffering from erotomania, 1843.”

Science is a bit like Doubting Thomas—it has to see the evidence before believing it. And sometimes even then it is just theories about what was or was not seen.

Way back in the early 1800s, many scientists thought it an idea to use visual representation, through illustrations and engraving, to help codify the system of identifying say, organs, bones, types of disease, and even mental illness. For example, a drawing of someone suffering from buboes caused by the pox would help diagnose a patient with similar buboes also caused by the pox. It was a logical, well-intended, and noble idea, one that helped create the many books on anatomy and disease which progressed the development of medicine from the 1700s on—most notably Gray’s Anatomy in 1858.

The physician and alienist, Sir Alexander Morison (1779—1866) pioneered the documentation of psychiatric illness during the early to mid-1800s. An “alienist” is the archaic term for a psychiatrist or psychologist. Morrison was inspecting physician at the Surrey Asylum and Bethlehem Hospital. He excelled in the diagnosis and treatment of those poor unfortunate people who suffered from mental illness. He was a wise and kindly old gent, who wrote two texts of great importance on psychiatric illness—Outlines of Lectures on Mental Diseases (1826), and Cases of Mental Disease, with Practical Observations on the Medical Treatment (1828). But these were but a warm-up for his illustrated volume The Physiognomy of Mental Diseases in 1840.

The Physiognomy of Mental Diseases contained descriptions of the various types of mental illness, case studies of various patients from a selection of England’s psychiatric hospitals, and some possible treatments. At the time, psychiatric care was going through a much-needed overhaul, with patients being treated as suffering from a (possibly) curable disease rather than being written-off as possessed by demons or just too fucked-up to no longer defined as human and dumped in bedlam where they were often exhibited to the amusement of the paying public. Morrison devised (whether by himself or in collaboration is unclear) the idea of illustrating his book on The Physiognomy of Mental Diseases with a series of portrait engravings of the patients whose case studies he was describing. It was a very useful idea.

However, it does suggest that mental illness can always be identified through a patient’s facial expressions—as if there are certain universal physical attributes that define all types of mental illness. Moreover, such drawings were open to possible caricature with artists exaggerating certain facial tics or expressions which may or may not be relevant. Morrison’s approach was valued until the 1850s, when the photograph was deemed to be the more scientific and reliable choice for documenting mental illness by his successor at the Surrey Asylum, the physician and pioneering photographer Hugh Welch Diamond.

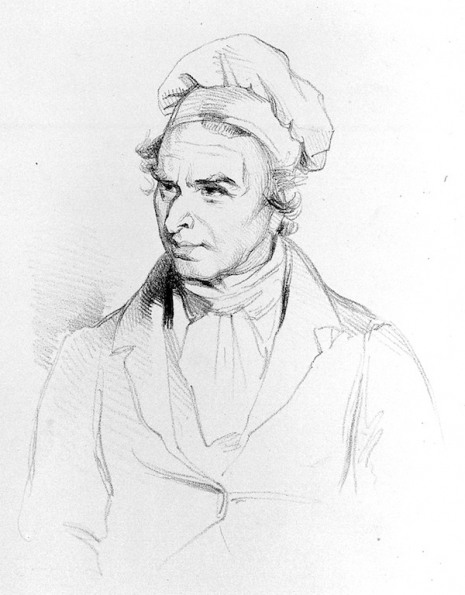

Portrait of 20-year-old female mental patient.

More engravings from ‘The Physiognomy of Mental Diseases,’ after the jump…