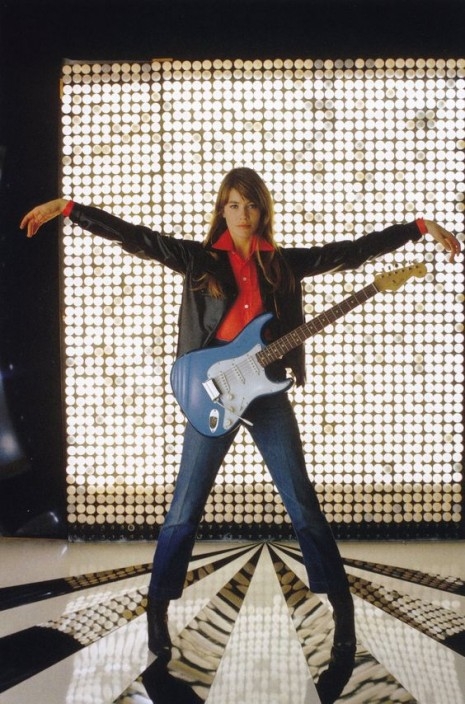

I recently read the Feral House publication, The Despair of Monkeys and Other Trifles: A Memoir by the great French singer/songwriter Françoise Hardy and got the absolute pleasure of discovering how rich and dynamic her life has been. Rarely have I read a book where a woman musician has talked about the way she has managed her career (or how she has been managed) and made herself vulnerable in this way. She is honest about her own desires, strengths and interests and—most wonderfully—she talks at length about the actual music making process and her genuine opinions and needs in recording sessions and throughout her tenure as a musical artist. These strong discussions are a breath of fresh air in a world where women in the musical world are rarely heard from. What a book!

Hardy’s story itself is fascinating from beginning to end. Filled with heartbreak, joy, adventure and intimately fascinating details about family, love, spirituality and world change. Guest appearances from people like Johnny Hallyday, Serge Gainsbourg, Malcolm McLaren and (of course) husband Jacques Dutronc amongst many others. This book is a solid read about an amazing artist and figure that has produced incredible work.

I was lucky enough to be able to interview her by email about her memoir. Thanks so much to Françoise Hardy and Feral House for this.

Your passion for music and love for your work is clear in this book. You also have a keen respect for the musical engineers who recorded and produced your work. Do you think most of today’s musicians no longer possess that kind of dedication?

Musicians, from yesterday or today, of course, know the vital importance of a good sound engineer, even if young composers and producers have more skills in a recording session. Today I am worried by excessive production. There are so many new singers everywhere, every day. It’s the same thing with books and movies. Too much production kills the artistic elements. As you know, media looks for efficiency rather than for quality. They are only interested in the short term and don’t care enough for timeless melodies.

You mention working with modern figures like Iggy Pop and Damon Albarn and those these were quite positive experiences versus the commercialistic result of the McLaren project. Can you expand on why you connected with these two?

I like and admire Iggy Pop and Damon Albarn very much, and I think that Malcolm McLaren’s album Paris is really great. But, these three collaborations were not significant to our respective careers. For instance, tremendous musicians like Michel Berger and Gabriel Yared have been far, far more important to my work and me as we shared many more connections between their musical world and mine.

In your memoir, you discuss your studies on psychology in the 1980s. One of the only courses that you say was “worth the trouble” was the one you took on the Tarot with Alejandro Jodorowsky. Can you talk about why that was such an important course, what learning from him was like and how it assisted you at that point in your life?

Alejandro Jodorowsky has a fascinating and robust personality. His vision of the Tarot de Marseille is very personal, very original and exciting. But Tarot de Marseille is complex like astrology, like graphology, like every science, human or exact. To be able to understand its symbolism and to use it, for improving the understanding of who you are, who somebody else is, and how to help in this way, requires a whole life of meaningful investigation. I was lucky enough to meet in 1974 a French astrologer, Jean-Pierre Nicola, a genius who has re-invented astrology – thanks to his intelligent and scientific connections between astrological symbolism and the rhythms and cycles of the solar system which are partly conditioning us, whether we like it or not. But the information that can be given by astrology about our many conditionings is limited. So I went to Jodorowsky’s three-day course because I was curious.

I have also studied graphology for a long time and have attended numerous classes taught by clever professional graphologists over the course of many years, but at some point, I had to give up because it would have required me to dedicate the rest of my life to it to become an expert. But my studies began with astrology, so I continued with it.

Your connection to spiritualism, astrology and non-Western practices is very strong and you express these things beautifully in your memoir. Do you think this has had an effect on your music?

I don’t think so. For me, music is the expression of deep emotions, deep feelings, a sublimation of human pains. Human science is like any science, it appeals to discernment, thinking, understanding, intelligence… It is mental, not sentimental.

Continues after the jump…