This is a guest post from veteran rock journalist Michael Simmons

In 1967-68 I was office boy at a short-lived magazine that my father published called Cheetah. Of Bar Mitzvah age, I considered myself a man, one who had thoroughly absorbed all tributaries of what is now called the counterculture, especially its music simply called ROCK, having dispensed with its appendage of “…and roll.” In the wake of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper and Bob Dylan, rock music was Gabriel’s electric horn for me and my young hirsute comrades, heralding the emergence of the holy in all God’s chillun, and love and peace and general groovyosity. Cheetah had a two-fold mandate: 1) to present a well-writ and designed, slick-papered mag for hippies and 2) to turn a profit. It usually succeeded in the former, but completely failed at the latter.

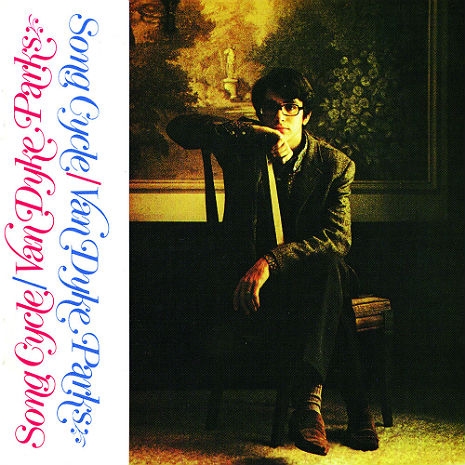

Before its demise, some of the best journalistic minds of the ‘60s generation contributed to Cheetah, including Paul Krassner, Ed Sanders, Doon Arbus, Richard Goldstein, Robert Christgau, Ellen Willis – even Tom Wolfe. Original editor Jules Siegel wrote a transfixing piece for the first issue called “Goodbye Surfing, Hello God” that was the first public announcement that Brian Wilson was writing “a teenage symphony to God” that would be the next Beach Boys album called SMiLE and that Brian was veering twixt visionary and paranoiac. Another truly fine scribe named Tom Nolan wrote a profile of a guy named Van Dyke Parks and his new album called Song Cycle.

Months before Nolan’s feature ran, everybody at Cheetah – editors, writers, the art department, and a mannish boy with my name – had flipped their Beatle wigs over a single by one George Washington Brown called “Donovan’s Colours.” It was a (mostly) instrumental version of Donovan Leitch’s melodically winning “Colours,” but it sounded like nothing else in the pop – or any other known – universe. Brown’s piece begins with the sound of a coin fed into a jukebox followed by the most delightfully bright piano that plays the tune of “Colours” and is soon joined by marimbas, a Pet Sounds-ish bass clarinet, swirling organ and castanets that imitate the sound of a music box being wound-up. Indeed the track has a music box feel though the repetition of Donovan’s melody, repeated modulations and tempo changes also remind one of a Chinese box—once opened it keeps revealing other boxes inside—or an unsolvable Rubik’s Cube that can be twisted every which colorful way without ever resolving. A mere seven words from Donovan’s song are sung, followed by an avian Dixieland clarinet: “Blue is the color of the sky.” Like the sky, “Donovan’s Colours” is wondrous, limitless—infinity contained in three minutes and 41 seconds.

In Tom Nolan’s aforementioned Cheetah profile of Van Dyke Parks, he tells a very funny story of hanging in a recording studio with Moby Grape listening to them bandy rumors about the identity of that George Washington Brown fella and the then-ongoing construction of “Donovan’s Colours.” Something about Brown being this wealthy guy who lives in South America and who’s recording bits and pieces and sending it to session man Van Dyke Parks in L.A. who’s splicing it together. All bullshit, of course. Eventually it was revealed that Brown was Parks, the studio musician, composer, producer and arranger who had written the lyrics for the Beach Boys’ “Heroes and Villains” and was Brian Wilson’s designated lyricist for SMiLE. He says today that he didn’t put his name on it because “I craved anonymity, so I adopted a nom de guerre.”

Van Dyke thought it would be a hit and was wary of public scrutiny. We at Cheetah all thought it would be a hit, as did virtually every critic in the nascent rock press. Warner Brothers Records then paid for VDP to record a solo album that would become Song Cycle. It’s The Great Overlooked Classic Of American Popular Music and like “Donovan’s Colours” (which is on the album), it’s a sui generis set of music that emanates from one man and one man only. The sounds of folk songs, Broadway show tunes, film scores, Charles Ives and Erik Satie all naturally blend. It’s psychedelic—not via clichés of electric sitars and fuzz boxes, but in the word’s literal definition of mind-manifesting. The Beatles and Dylan had smashed all the conventions of pop music and were the toppermost of the poppermost. Why not Van Dyke Parks? For all the media yap about The Rock Revolution, neither album nor single fit into commercial radio’s idea of what rock music should sound like – too eclectic, too intelligent – yes Virginia, “too intelligent” was a very real concept then, as now, in the United States Of America. And neither in any way rawked. So for the most part, the hippie hordes – however expansive their consciousness—never got to hear Song Cycle and it sold bupkis.

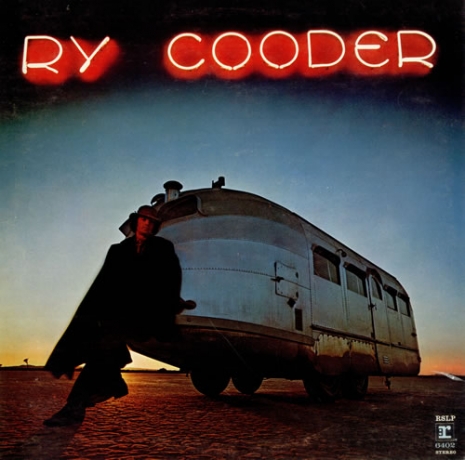

Van Dyke soldiered on despite the commercial failure, continued to make solo albums (including collaborating with Brian Wilson on Orange Crate Art), produced and/or arranged singular recordings for – among others—Randy Newman, Ry Cooder, Little Feat, Allen Toussaint, Harry Nilsson, Phil Ochs, Loudon Wainwright, Arlo Guthrie, Bonnie Raitt, and The Esso Trinidad Steel Band and The Mighty Sparrow (he loves steel drums and calypso). He still resides in the moment and scouts horizons, championing Rufus Wainwright and producing discs for other young ‘uns like Joanna Newsom and Inara George (daughter of his late friend Lowell George). VDP has scored films and commercials, written children’s books, and acted in movies and T.V.

In keeping with the awry pattern of American cultural illiteracy, he’s more respected in Europe, Japan, and Australia than in his own country. Last year, U.K. label Bella Union reissued his first three solo albums (Song Cycle, Discover America, Clang Of The Yankee Reaper) and will release his “orchestral fantasy” Super Chief: Music For The Silver Screen [] on limited vinyl on April 20 and his latest CD collection Songs Cycled on May 6. There’s also many delights available on VDP’s website.

For those near or in Los Angeles, Van Dyke plays at McCabe’s this Saturday, March 30. Inara George will join him during his set and New Orleans piano wiz Tom McDermott is also on the bill. The early show is sold out, but there are still late show tix available.

Van Dyke Parks remains in forward motion despite the fickle tastes of the Entertainment-Industrial Complex. An eloquent raconteur and great wit, he’s philosophical about the vagaries of his life as a working musician. “As Jefferson noted ‘Show men your depths, and they will ford your shallows,’” he wrote to me recently.

“That’s why I’m a Chevy guy,” he added.

Posted by Richard Metzger

|

03.29.2013

02:26 pm

|