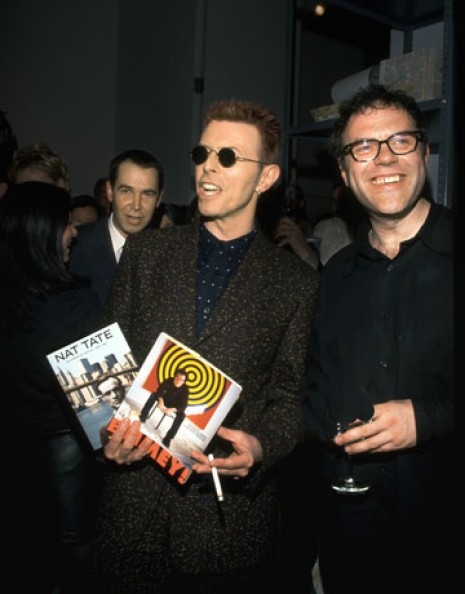

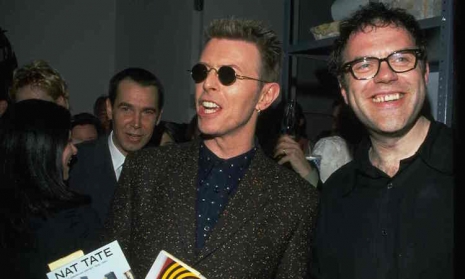

David Bowie and art critic Matthew Collings at the the launch party for William Boyd’s book on Nat Tate, 1998. Jeff Koons is in the background.

This week it was announced that David Bowie’s private art collection will be revealed to the public for first time, in an exhibition to be held at Sotheby’s in London starting July 20 as well as other locations. An auction of the works is expected eventually.

The collection of Bowie, who passed away this January, was held in high regard and included notable works by Damien Hirst, Henry Moore, Gilbert & George, and Patrick Caulfield. One of the most prized items in the collection is a 1984 canvas by Jean-Michel Basquiat called Air Power, which is expected to fetch in excess of $2 million at auction.

Bowie is said to have had excellent taste in art, which makes perfect sense. The occasion of an exhibition and auction of Bowie’s art holdings is also a reminder of a curious episode from the late 1990s when Bowie totally punked the New York City art world.

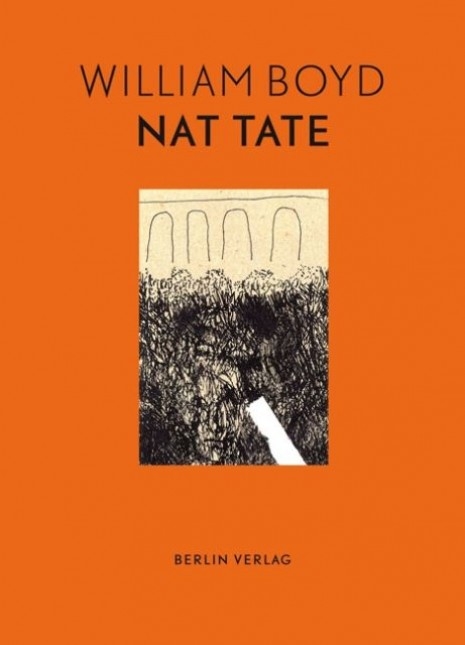

In 1998 Bowie joined the editorial board of a magazine called Modern Painters, and he also set up a publishing company called 21 that would focus on art books. One of 21’s first books was a volume by noted novelist William Boyd (Brazzaville Beach, The Blue Afternoon) celebrating an artist whose life had been cut short with the title Nat Tate: An American Artist 1928-1960. You can buy that book today on Amazon.

Nat Tate was born in 1928 in New Jersey; his father was absentee, and his mother died in a car accident when Tate was eight years old. His mother had worked as a maid for a wealthy family in Long Island—upon the death of Tate’s mother her employers adopted the child. Tate studied under Hans Hofmann in the late 1940s and became part of the abstract art scene in New York in the early 1950s. Tate was an alcoholic who was obsessed with the work of Georges Braque. In early 1960 Tate committed suicide by jumping off the Staten Island Ferry. Somewhat like Franz Kafka had intended, Tate had a tendency to destroy his own work, and left little in the way behind for audiences to appreciate.

Trouble was, there never was any such artist as Nat Tate. Boyd, with a key assist from Bowie, had made him up. A lot of people took the bait, and claimed to remember exhibitions of Tate’s that had never happened. People should have given more thought to Boyd’s profession of novelist.

William Boyd

It was a thoroughly successful literary, or artistic hoax, à la Sidd Finch or Ern Malley. It’s also a bit reminiscent of a hoax of 2006, in which British art students invented a German noise rock band from the 1970s named Lustfaust—we covered that one here.

Boyd delivered a hifalutin justification for the prank, saying, “I’d been toying with the idea of how things moved from fact to fiction, and I wanted to prove something fictive could prove factual.” But it’s pretty obvious that the primary motivation was that it’s fun to catch a lot of supposed art experts out on their own terrain. Also, it’s just fun to concoct fake footnotes and stuff like that:

Much of the illusion was created in the details, the footnotes and in getting the book published in Germany to make it look like an authentic art monograph. ... I went to a lot of trouble to get things right. I created the “surviving” artworks that were featured in the illustrations and spent ages hunting through antique and junk shops for photos of unknown people, whom I could caption as being close friends and relatives.

Gore Vidal (in on the joke) supplied a suitably gushing pullquote for the cover. Picasso’s biographer, John Richardson, gave them a bogus anecdote:

Vidal allowed himself to be quoted in the book saying, ‘Tate was essentially dignified, though always drunk and with nothing to say,’ while Richardson told of how Tate had been having lunch with Picasso when he came to visit. It was these details that made it. People stopped wondering why they hadn’t heard of Tate when Vidal, Picasso and Richardson started appearing.

At the launch party for Boyd’s book on Tate, which was pointedly held on April 1, 1998, David Lister, arts editor for the Independent at the time who was also in on the hoax, spent the event asking guests for their reminiscences about Tate. Curiously, a fair number vividly remembered attending a retrospective of his in the late 1960s.

More after the jump…