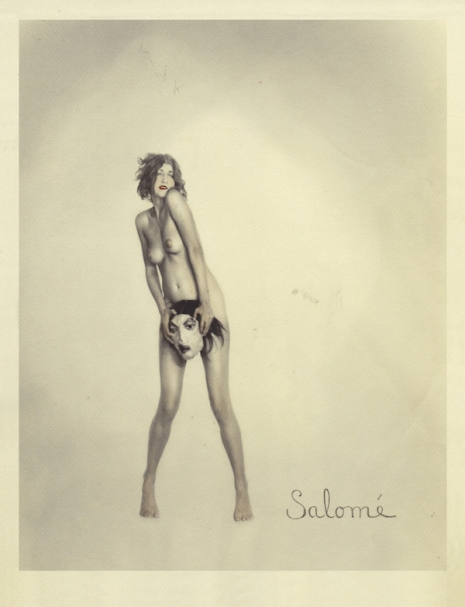

‘Salome’ (1924).

A chance encounter with big shot director Cecil B. DeMille gave photographer William Mortensen his first job in Hollywood. It was the kind of lucky break that would look hokey as a plot device in a B-movie. Mortensen was working as a gardener but was soon on the set of DeMille’s King of Kings (1927), then designing voodoo masks for Lon Chaney’s movie West of Zanzibar, and then ending-up taking publicity shots and portraits of stars like Marlene Dietrich, Rudolph Valentino, and the original “It girl” Clara Bow.

Before Hollywood, Mortensen had spent his time traveling around Europe in the early 1920s soaking up all that fancy art and culture. He got hep to all the Old Masters like Goya and Rembrandt. This together with his experience of working on films made Mortensen approach photography in a wholly original way.

It was a similar kind of thing that had once happened to writer James Joyce, who had opened the first cinema in Dublin in 1908. Joyce realized traditional story-telling could not compete with movies. Why write a page describing the looks of some lantern-jawed hero when a movie could transmit such information in an instant? Movies taught Joyce to rethink literature—and so he wrote Ulysses.

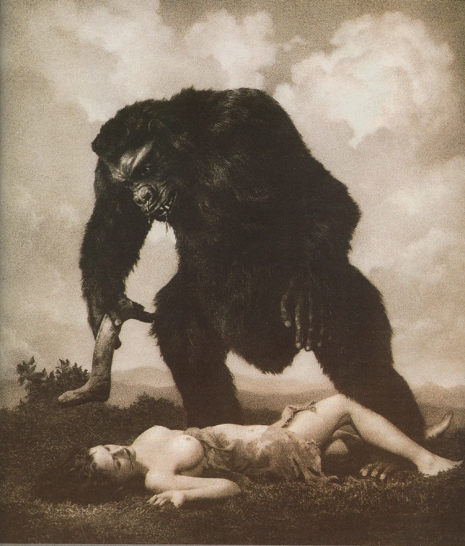

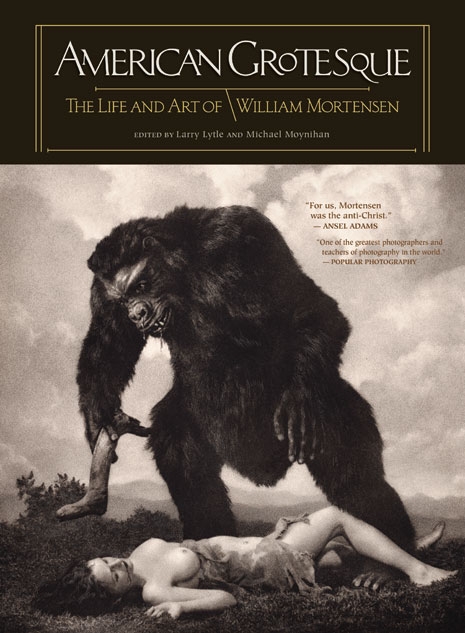

Mortensen made photographs that mixed painting, drawing, theater, and movies. He manipulated the image to create something more than just a straight photographic representation. His approach was anathema to the more traditionalist photographers like Ansell Adams, who called Mortensen the “anti-Christ” for what he did to photography.

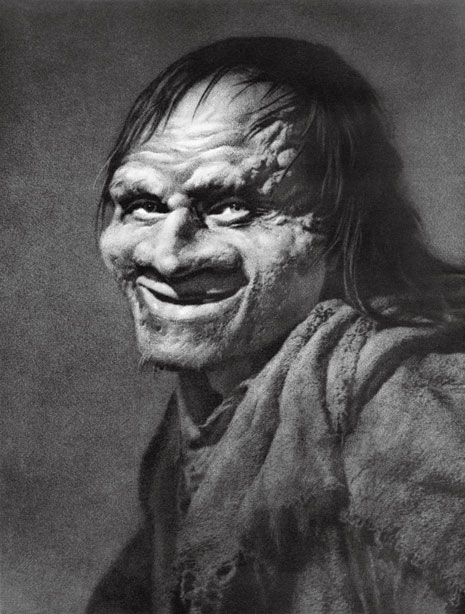

Mortensen produced beautiful, strange, often dark and Gothic, sometimes brutal, though usually erotically charged pictures. While other photographers sought realism, Mortensen used props and gowns and his own vivid imagination to enhance each picture. He went on to have some success but fell out of step with the rise of photojournalism that came out of the Second World War and was (sadly) largely forgotten by the time of his death in 1965. In more recent years, Mortensen has been rightly praised for his photographic genius. What I am intrigued by in Mortensen’s work, is his design and use of masks (including one of “scream queen” Fay Wray) in his photographic work—from which a small selection of which can be seen below.

‘Masked Woman’ (1926).

‘Fay Wray.’

More of Mortensen’s masks, after the jump…