I had never heard of the Yakuza until I tuned in one night to a Robert Mitchum movie back in the 1970s. Here was big Bob dealing with bad boy Japanese gangsters in a clash of east meets west. The film was simply titled The Yakuza. It was written by brothers Leonard and Paul Schrader—their first hit screenplay and one in which can be seen some of the themes they would later develop individually and together in movies like Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and Mishima. I liked the film and was greatly intrigued by the rituals depicted in it and the code of honor by which these dangerous, violent gangsters lived their lives.

One ritual in particular, the chopping off of the top of the small finger as a payment or apology for any wrong-doing, I thought bizarre and hardly punishment at all until I later discovered its historic symbolism. The removal of the tip made it difficult for an individual to hold their samurai sword. The sword was gripped tight by the bottom three fingers while flexibility and movement was produced by index finger and thumb. To lose a chunk of a fingertip or the whole pinky was ultimately a death sentence—as the punished yakuza would eventually be unable to defend themselves in a fight.

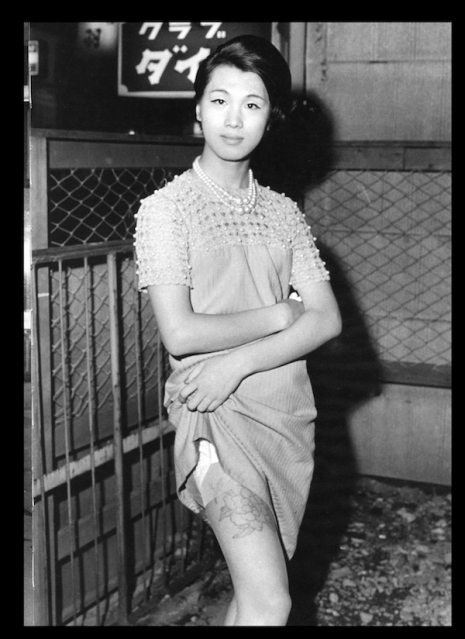

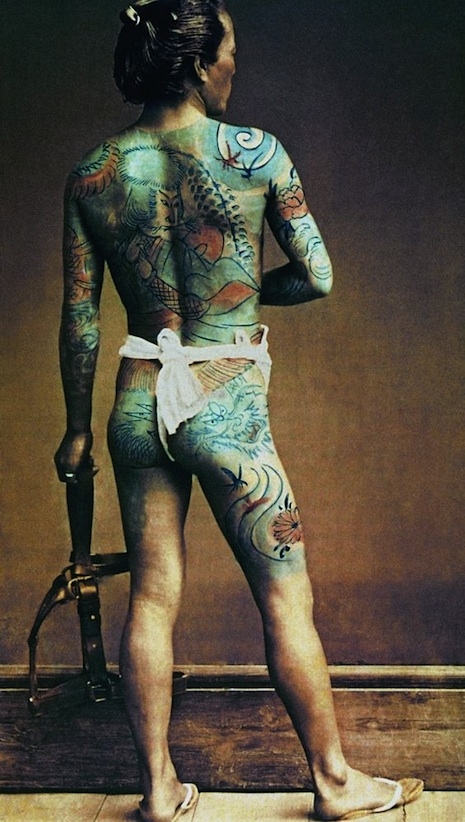

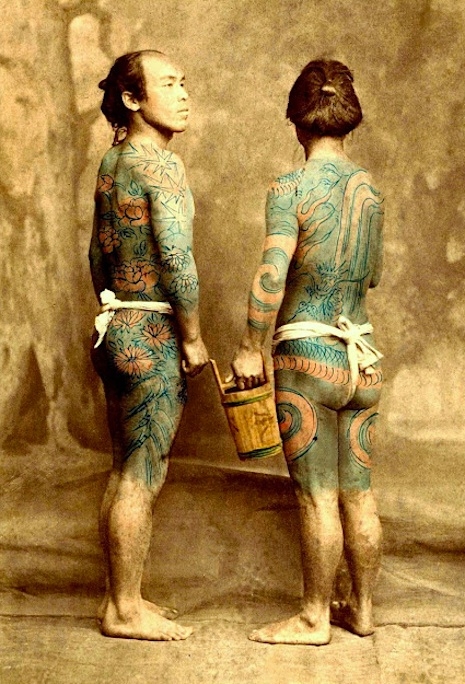

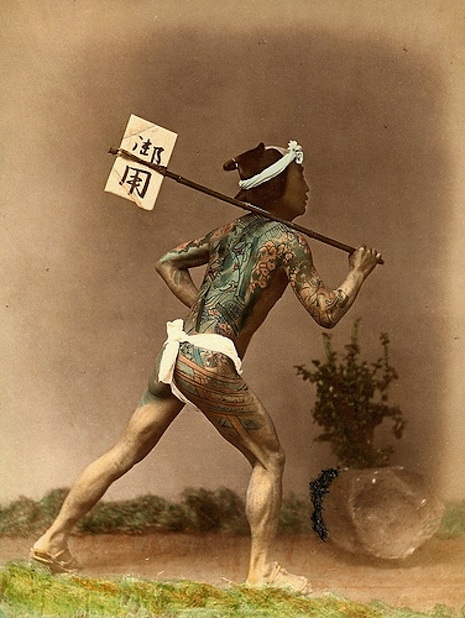

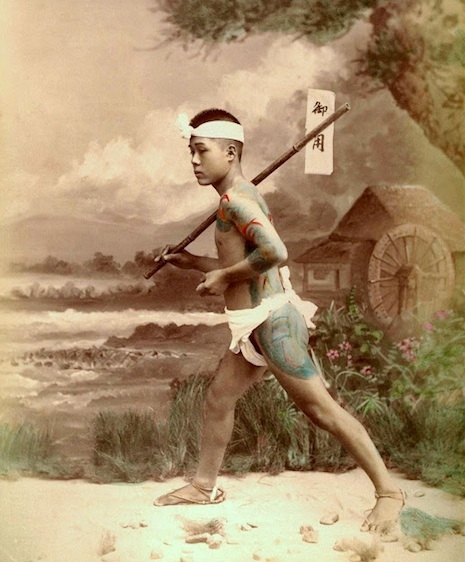

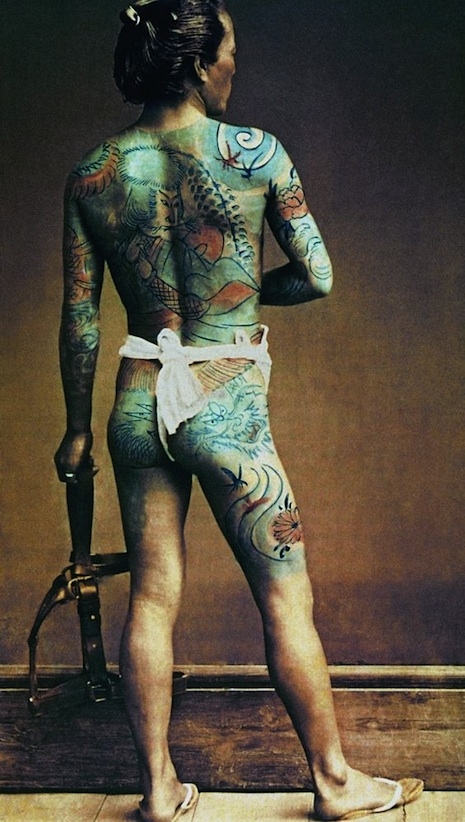

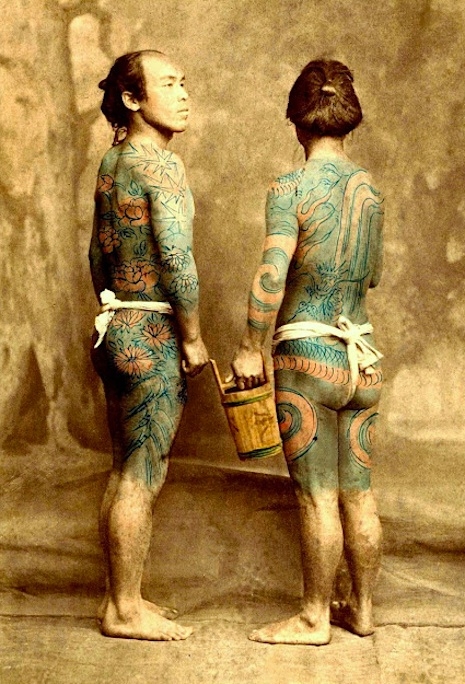

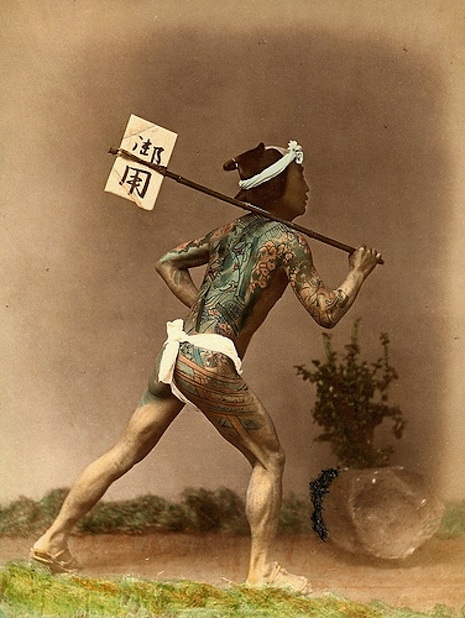

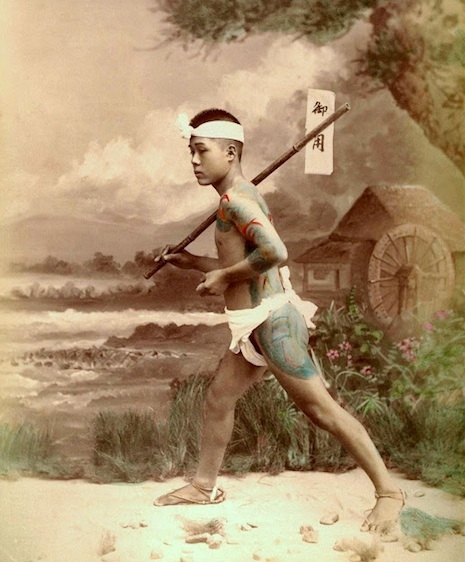

The film also picked up on the awesome body tattoos these way heavy gangsters sported. Whole bodies decorated with elaborate illustrations of beautiful maidens, tranquil landscapes, and grinning demons. Like bad boy superheroes, these guys could walk around in their suits and ties all day and no one would know they were Yakuza. Come nightfall, in the comfort of their own gangland den, the clothes would come off and the tatts would be displayed.

These tattoos or irezumi as they’re called in Japan—a word that literally mean insert ink—were originally representative of an individual’s spirituality or biography. This lasted for a good two-three thousand years. Then around the Kofun era (330-600AD), tattoos were considered a symbol of being criminal or lower class. Their popularity fluctuated until tattooing was outlawed sometime around the Meiji era (1868-1912), when Japan moved from a feudal world into a unified country. Tattoos were seen as an embarrassing symbol of Japan’s uncivilised past. The practice moved underground—continued by criminal gangs, who tattooed the unexposed parts of their bodies. Hence the all-over body tattoos many yakuza carry to this day on their skin. These tattoos are “hand-poked”—that is the ink is put under the skin by using sharpened bamboo spears or small handmade needles. It is a long, painful and laborious process but one that most yakuza accept as part of the ritual of being a gang member.

The Meiji era also brought an end to the samurai warriors, who were outlawed and conscripted into the army. Some chose to join the yakuza instead—as many yakuza had fought alongside samurai for local shoguns. The issue of body tattoos becomes complicated as there were samurai who sported such irezumi as a means of identification should they be killed on the battlefield. As samurais faded, the criminal fraternity thrived. Today yakuza play a major role in Japan—both in criminal activity (prostitution, money laundering, people trafficking) and legitimately in media and politics. The yakuza keep drugs out of Japan, they also organize charity and aid relief for disaster victims. Most Japanese accept the yakuza as a necessary part of national life. Each yakuza family or gang have their own set of rules and regulations which differ group to group and gang to gang.

These hand-painted photographs from the late 1800s and early 1900s depict members of the yakuza displaying their gang related tattoos. Some have posed in relation to their standing within the gang, most have kept their faces hidden, but each has a different style of tattoo inked on their body.

More vintage yakuza tattoos, after the jump….