There is a humorous recipe for “Martin Burgers” that Dean Martin came up with (grill some ground beef, pour a shot of bourbon, done!) that was posted by Letters of Note that reminded me of my own encounter with the legendary entertainer. It also involves hamburgers. And bourbon. It’s one of my favorite stories to tell. Gather ‘round, children…

This event took place in, I think, 1992, when I was 26 years old. I’d recently read Nick Tosches’ excellent biography of Martin, Dino: Living High in the Dirty Business of Dreams, and I was on a Dean Martin “kick” that culminated in me having a professional photo house make me a 6 ft. by 6 ft. photo mural of the above Dean Martin album cover (which Boing Boing’s Mark Fraunenfelder once described in Wired. I still have it, but it’s not hanging up).

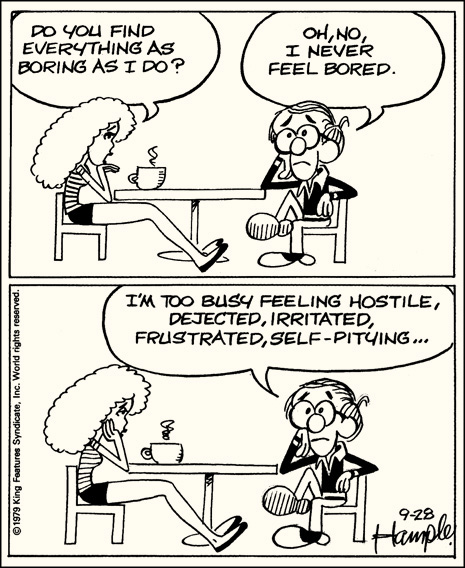

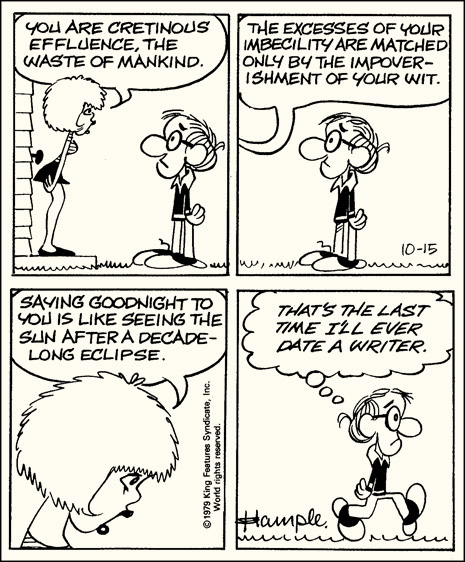

I was absolutely fascinated by Dean Martin, the very definition of the devil-may-care roué who truly wasn’t impressed by anything or anyone. Beauty? He had more women than he knew what to do with. Fame? Come on. Money? Please! Dino didn’t care if you were the President of the United States, some hot piece of ass or the head of the Las Vegas Mafia. The man, to paraphrase the Super Furry Animals, simply did not give a fuck. Weltschmerz as an art form! Ennui deluxe! I reckon Dean Martin must’ve been the coolest man ever to live.

Janet Charlton, the Star magazine gossip columnist, seen frequently on Access Hollywood, ET and similar shows back then, told me that Dean Martin—who was generally thought to be a complete recluse, sitting home drunk in an armchair watching movie westerns, basically—did in fact dine out nearly every night at the Hamburger Hamlet (an upscale LA burger chain) on Doheny Drive in Beverly Hills.

A few weeks after she told me this, Mike and Roni, two pals of mine from New York, arrived on my doorstep unannounced. They seemed quite amused by my gigantic Dean Martin album cover and when I told them that he was a regular at the Doheny Drive Hamburger Hamlet, we all three enthusiastically agreed that this was where we’d dine that evening. And we brought a camera.

I generally like the Hamburger Hamlet chain, but the one in Beverly Hills has got to be THE restaurant in LA with the oldest clientele, hands down. It’s the sort of place where grandparents take their grandchildren out to eat and the grandchildren are in their seventies. I’m talking OLD. Palm Springs old. Miami Beach old. A few of the faces seemed extremely familiar from sixties television, character actors who might have been on The Beverly Hillbillies, Bonanza or Green Acres, but who I could not place exactly due to the passing of years. What made walking into this place seem even more surreal is that it is merely a block away from all the rock clubs on the Sunset Strip.

So we get there and valet the car. I asked the maître d’, who must’ve been all of 19, if we could be seated near Dean Martin’s table. He took the money I put into his hand and looked at me like I was an idiot. Not a stalker mind you, but a complete idiot. “Oookay,” he whistled dismissively and rolled his eyes.

Martin was not there, he told us, but they did expect him. So we sat in the lobby and we waited. And waited. And waited. After looking at the grub the waiters were serving up, we decided he wasn’t going to show up and split to grab a steak at Dan Tana’s. As the valet handed me my car keys I asked him, “We heard that Dean Martin eats here all the time. When is a good day to see him?” He replied “Mr Martin? Oh, his chauffeur just phoned ahead, he’ll be here any minute.”

I tossed my keys back to him and we returned inside and were seated in the back section of the restaurant. Within a few minutes, the sultan of suave, secret agent Matt Helm, the roast-master general hisself, Dean Martin stumbled in, completely shit-faced. His eyes were bloodshot red and he looked old and he looked drunk. Very drunk. It was probably a very good thing that he could afford to employ a full-time driver, let’s just say…

As soon as he took his seat, the waiter slammed down several shots of bourbon and two beers in front of him. Dino downed two shots immediately and two more were placed in front of him in a flash.

We made our move before they brought his food out. Roni got her camera ready and asked politely, “Mr. Martin, can I get a picture of you with these guys? They’re big fans of yours!”

He looked at us like “Yeah, right” and replied quietly “Most of my fans these days are old broads.”

I told him about my giant 6 ft. mural of his album cover and that I was born and raised in Wheeling, WV, just across the Ohio River from Martin’s hometown of Steubenville, OH. He softened a bit and said “I remember Wheeling, WV. I used to swim there and mess around and hang out there when I was a boy.” (No matter how slowly I ask you to imagine this sentence being said, you’re going to make it faster in your mind than he spoke it. Pause after each word as if there is a period… or a wheeze).

Today Steubenville has dozens of things named after Dean Martin (they also hold a yearly Dean Martin festival). I asked him when was the last time he’d visited his hometown and he just snickered.

“Do you mind if we get a picture?” Roni asked again.

“I don’t think they allow that here,” he demurred, trying to avoid it.

“Who’s gonna stop us? Let’s just do it,” she replied.

Martin shook his head and exhaled with undisguised annoyance, parted his lips and clicked on a a very fake smile. Through his gritted teeth he said “Go ahead, I don’t give a shit.” Something about his manner let Mike and I know that he meant NOW, so we squatted beside his chair.

After the flash went off, his smile vanished, he looked down at his drink and completely ignored us. We knew this was our cue to leave and we took it. Outside his limo was waiting. It sported a vanity plate reading “DRUNKY.”

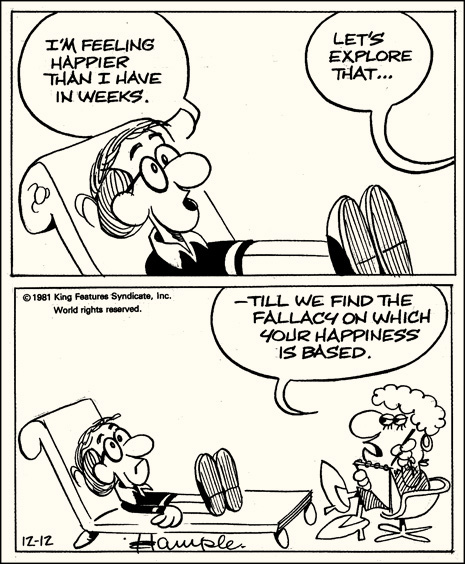

The story doesn’t end there: Two weeks later I get a package of two big prints of the photo and several smaller ones from Roni. I laughed my ass off, DELIGHTED at seeing this memento of our loopy encounter with Dino. I left them out on the kitchen counter and every time I walked past them I grinned and marveled at the fact that a photo existed with Dean Martin and ME in it.

Then the phone rang. It was Roni asking had I gotten the package. I was looking down at the picture when she asked me: “Did you notice that his…”

No, I hadn’t noticed it, but I did then: His pants had been unfastened and un-zipped old man-style so his gut could hang out and the camera had caught this!

The photo I had been admiring all day became a million times better before my very eyes.

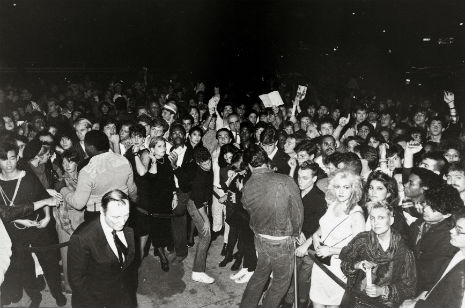

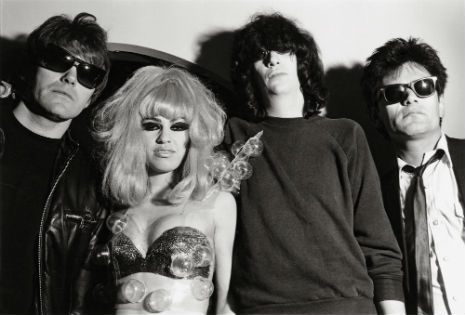

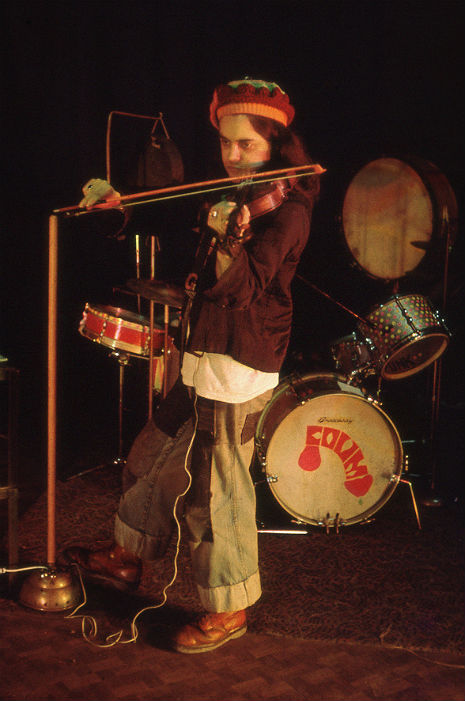

But the story doesn’t end there, either: At the time, I was in the middle of writing a script with Kramer (he of Bongwater and Shimmy-Disc fame) and I gave him one of the larger prints, which he hung in his Noise New Jersey studio. Around this time, he and Penn Jillette had formed a band called Captain Howdy and they were doing a bit of recording. Apparently Penn asked Kramer who the old guy in the photo was, but he refused to believe it when told that it was Dean Martin. Eventually he relented, and the Captain Howdy song “Dino’s Head” was apparently inspired in part by the below photo (and Penn getting to use Dean Martin’s “special” German shower head when Penn & Teller were performing in Las Vegas, as is explained in the song).

Click on photo to view larger image.

It doesn’t end there, either. Last month, HBO’s Real Time with Bill Maher used the Dino photo in a bit comparing JFK to Reagan, as seen below