There are too many writers in the world. Too many bad writers. I’ll include myself in that group. No, not false modesty, just how it rolls for the sake of this tale. But you see I have an excuse. I use my bad writing to introduce you to good writing, great writing, writing that will change and inspire you. What purpose is there for bad writing other than to make you yearn for truly great writing?

So, here you go…

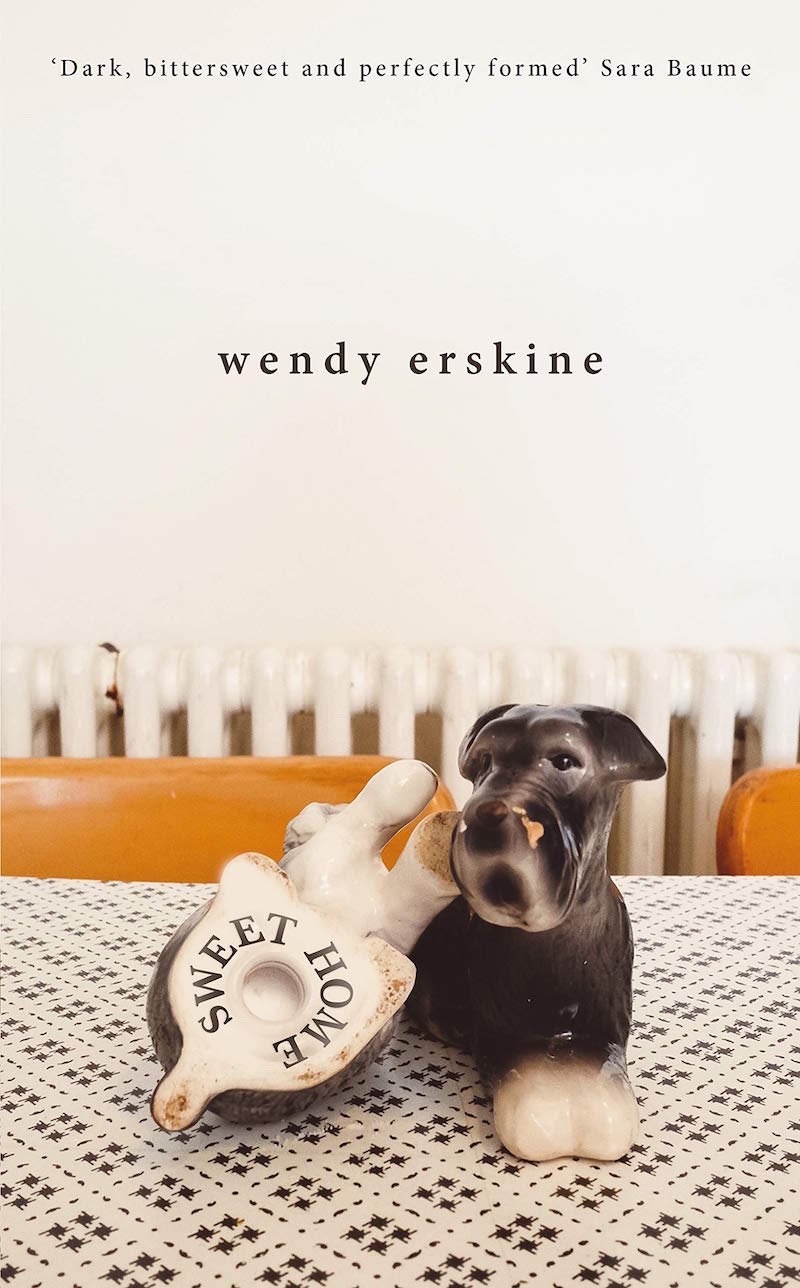

Wendy Erskine is a great writer. A true original. A writer whose first collection of short stories Sweet Home contains some of the finest tales ever written. Clever, sassy, nuanced, with a rich seam of dark humor. Erskine’s stories of working class life in East Belfast have been hailed by critics as works of brilliance and her book has been nominated for several awards. Though experience suggests Erskine has worked on these stories and crafted them into things of beauty, they appear so fresh, so fully formed, so organic, that they may have just fallen like ripe fruit straight from the tree.

Go on, take a bite.

Born and raised in Northern Ireland during The Troubles that most dangerous and murderous time in the province’s history, Erskine has produced a wry, wise, funny, and utterly compelling collection of stories. She is the kind of writer that makes you fall back in love with reading. A magician who pulls the Ace of Spades from behind your ear while you’re still wondering how it was removed from your tightly gripped hand in the first place.

Her collection of stories opens with a three-part tale that is compelling and disturbing in equal measure. “To All Their Dues” is centered around a beauty parlor, and the lives of three people: the owner Mo, the local villain Kyle, and his wife Grace. Kyle is a psychopathic character with a pulsing menace few crime novelists have ever imagined or described in such chillingly simple and unforgettable terms. But if that weren’t enough, wait till you meet his wife.

Erskine has a remarkable eye for detail, for character evinced through thought and action, that reminded me of John Updike, Fitzgerald, or the Scottish writer James Kelman.

That long thin scar, running along the inside of your thigh, lady in the grey cashmere, what caused that? Those arms like a box of After Eights, slit slit slit, why you doing that, you with your lovely crooked smile, why you doing that? The woman with the bruises round her neck, her hand fluttering to conceal them. Jeez missus, is your fella strangling you? Bt you don’t ask, why would you?

While the second tale “Inakeen” works, its ending felt slightly contrived in a way that J. G. Ballard sometimes forced his stories to fit a purpose. Even so, it’s a small quibble but is another story that sticks long after reading. “Observation” about two teenage girls and an older man is a powerful work about what’s left unsaid between knowing and action. “Locksmiths” is about the troubled relationship between a daughter and her mother just released from jail. “Last Supper” deals with a manager covering for two employees having sex in a diner’s restroom. “Arab States: Mind and Narrative” and the devastating “Sweet Home” (parts of which I had to stop reading because it hit me so hard) show a writer who is in full control of their talent and knows exactly what she wants to say and how best to say it.

But how to interview such a writer? By email of course. But let’s not get too serious, or ahead of ourselves. Let’s start our interview with Erskine as if this was for one of those teen-pop magazines like Smash Hits:

Writer of the Week: Wendy Erskine

Starsign: Taurus.

Favourite color: Duck egg blue.

First record bought: “Ma Baker” by Boney M.

Favourite food: Green papaya salad, really hot.

First gig: Depeche Mode, the Ulster Hall, 1983.

Favourite band: Velvet Underground.

Favourite singer: Small Faces era Steve Marriott

Favourite artist: Maurice van Tellingen

If you were Prime Minister/President what would be your first law: No one can earn100 times more than someone else.

A full interview with Wendy Erskine, after the jump…