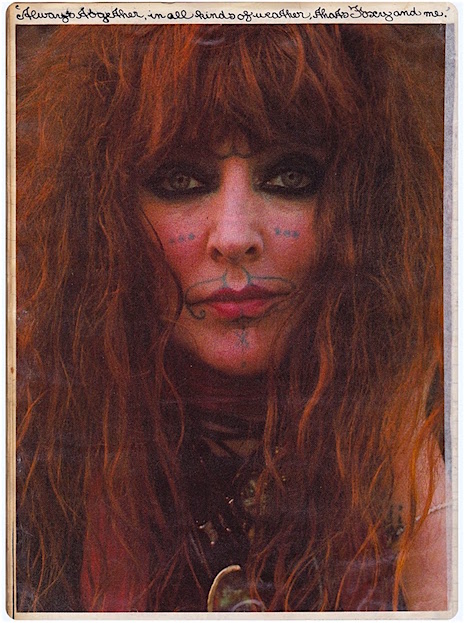

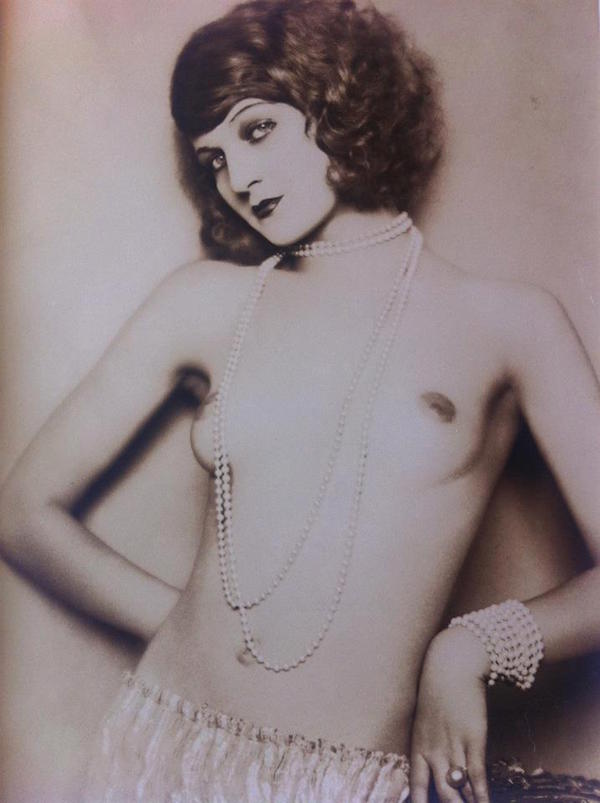

The woman with the shock of dyed red hair, her body wrapped in a fur coat, and a pet monkey grinning and holding tight to her neck was Anita Berber. She danced across the foyer of the Adlon Hotel opened her sable coat and revealed her lustrous naked body underneath. Men leered, goggle-eyed. Women giggled or turned their heads in shock and embarrassment.

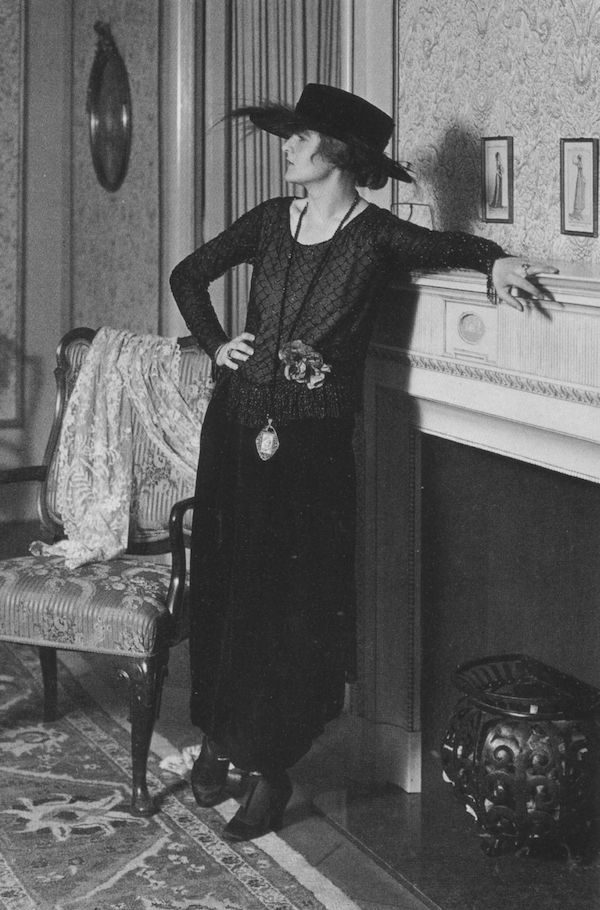

Anita Berber didn’t care. She liked to shock. She liked the attention. If she didn’t get it, she would shout and throw empty bottles or glasses on the floor. Smash! Berber was a dancer, an actor, a writer, and a model. She was called the “Goddess of the Night,” the “Priestess of Debauchery,” the very symbol of Weimar decadence, and a drug-addled degenerate. She was all these things and more. And during her brief life, Berber utterly scandalized Berlin during the 1920s. Not an easy task!

The daughter of two musicians, Anita Berber was born in Dresden in 1899. Her parents divorced when she was young, Berber was then raised by her grandmother. By sixteen, she quit the family home for the unpredictable life as a dancer in cabaret shows. The First World War was at its bloodiest height. The daily reports of casualties and death meant people were reckless with their passions. It was then that Berber started a series of relationships and dangerous habits that became her life.

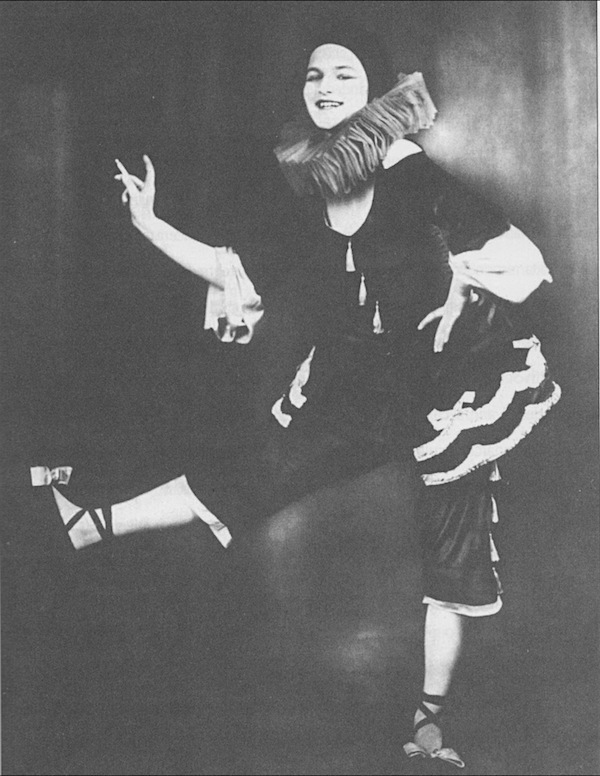

After the War, Berber began her career as a movie actor—starring opposite Conrad Veidt in The Story of Dida Ibsen in 1918 and then in Prostitution and Around the World in Eighty Days the following year. While Veidt went onto become a major movie star with a career in Hollywood, Berber’s career stalled and she became best known for her performances as a dancer, a sultry temptress or a drug-addled prostitute. With her dark bobbed hair and androgynous good looks, Berber created a style that was copied by Marlene Dietrich (who basically stole her act), Leni Riefenstahl who idolized Berber, was her understudy and had a brief intense relationship with her, and Louise Brooks, whose seductive image in Pandora’s Box was a copy of Berber’s. She had relationships with both men and women, seeing no difference in taking pleasures from either sex. Berber married in 1919, then left her husband—a man called Nathusius—for a woman called Susi Wanowski. The couple became a fixture of Berlin’s growing lesbian scene.

Berber enjoyed opium, hashish, heroin, and cocaine—which she kept secreted in a silver locket around her neck. She also had a strong predilection for ether and chloroform mixed together in a small china bowl, into which she scattered white rose petals. Once these were sufficiently marinated in this heady concoction, she ate the petals one by one until she fell into a delicious sleep.

Berber’s louche lifestyle coupled with her fame as a movie star and dancer meant she was the subject of gossip and cafe tittle-tattle. It was said over black sweet coffee she was once kept as a sex slave by a married woman and her fifteen-year-old daughter. It was claimed between mouthfuls of chocolate cake that she wandered through casinos and hotels flashing her naked body. While in the bars, it was overheard that she exhausted her lovers with her insatiable demands for sex.

Some of these tales were false. Most were true. But all of them kept Anita Berber fixed in the public’s imagination.

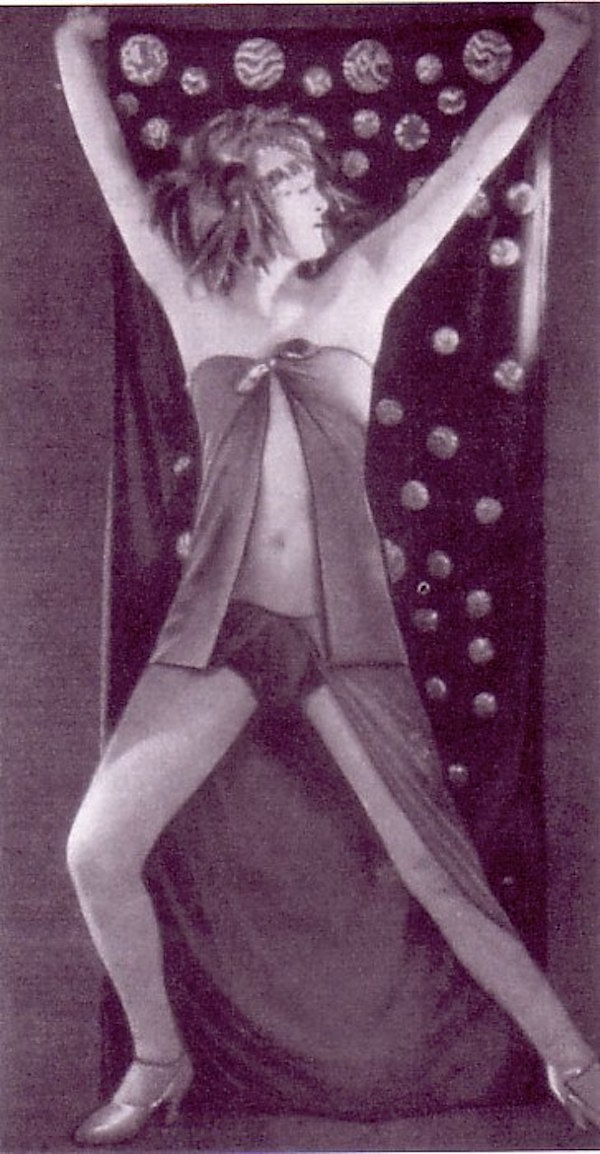

In 1921, she met and fell in love with the Sebastian Droste, a bisexual dancer who was known as a performer in Berlin’s gay bars and clubs. They became lovers and married in 1922. They formed a scandalous dance partnership choreographing and performing together in Expressionist “fantasias” like Suicide, Morphium, and Mad House. They also collaborated on a book of poetry and photographs called Die Tänze des Lasters, des Grauens und der Ekstase (Dances of Vice, Horror, and Ecstasy). A typical routine went something like this:

In the dance, “Menschen,” or, “People,” we find,

Only two people

Two naked people

Man

Woman

And both in a cage

Hard stiff horrible cages

The two king’s children sang songs

But with tears

The man smashes his cage

Tradition

Society

Convention he spits out.

Which is the kind of nonsense we nowadays associate with the overly pretentious rather than the naturally gifted…but at the time… You can imagine: shock, horror, and spilled sherry.

Berber’s and Groste’s relationship was intense, passionate, and drug-fueled. Because of her considerable use of cocaine, Berber often hurled champagne bottles at the audience if they failed to appreciate her genius. It was inevitable their marriage would not last long and they separated in 1923.

By the time Otto Dix painted his famous portrait of Berber in 1925, the years of drug abuse, frenetic lifestyle, and lack of nutrition was plain to see. The painting looks more like a woman in her fifties than a twenty-five-year-old. The woman who once scandalized Berlin with her androgynous looks, her erotic and seductive dances and her sultry on-screen appearance was no longer so appealing. Berber was out of favor as a younger generation of ingenues took over. She began touring her dance shows. During one such tour in Damascus, Berber became fatally ill with tuberculosis. She returned home to Berlin where she died “surrounded by empty morphine syringes” on November 10th, 1928. Anita Berber was twenty-nine. She was buried in a pauper’s grave and may have been long forgotten had it not been for Dix’s portrait that kept her legend alive.

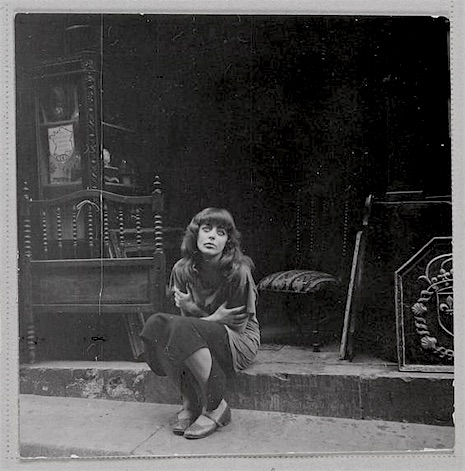

More photos of the ‘Priestess of Debauchery,’ after the jump…