There’s an horrific scene in Ben Wheatley’s latest film, the truly excellent A Field in England, which proves the merit of the old adage that the most gruesome moments in any movie are more effectively achieved when they are suggested rather than revealed.

In this particular scene, the character Whitehead (superbly played by Reece Shearsmith) is tortured by the diabolical O’Neill (another excellent performance from Michael Smiley). Rather than showing what happens, Wheatley audaciously keeps any physical violence out-of-vision, leaving only Shearsmith’s terrifying screams to suggest the worst, the very worst. It is one cinema’s genuinely horrific and visceral moments, and yet nothing is ever seen.

A Field in England confirms Ben Wheatley as the most talented and original film-maker to come out of Britain since the glory days of Ken Russell, Tony Richardson, Lindsay Anderson and John Boorman in the swinging sixties.

Unlike most young directors who show flair with one type of genre film before going on to make variations of the same time-and-again, Wheatley has shown with his first four films that he is an immensely talented and important film-maker, whose movies defy easy categorization yet engage their audience with intelligent and sometimes disturbing ideas.

His first major film Down Terrace was a blackly comic tale of murder and violence set in a working class family home, which Wheatley co-wrote with the film’s star Robin Hill. It was described as being like The Sopranos as directed by Mike Leigh. It’s a nice soundbite but doesn’t quite encapsulate the thrilling intelligence that was at work behind the camera.

Wheatley’s next film was the brutal, disturbing but utterly brilliant Kill List, which contained one of the most harrowing endings ever committed to celluloid. Kill List was written by Wheatley and his wife, the writer Amy Jump, and starred Neil Maskell, MyAnna Buring and the excellent Michael Smiley.

Having shown his aptitude for gangster and horror films, Wheatley then made the black comedy Sightseers, written by the film’s lead actors Alice Lowe and Steve Oram, in conjunction with Amy Jump.

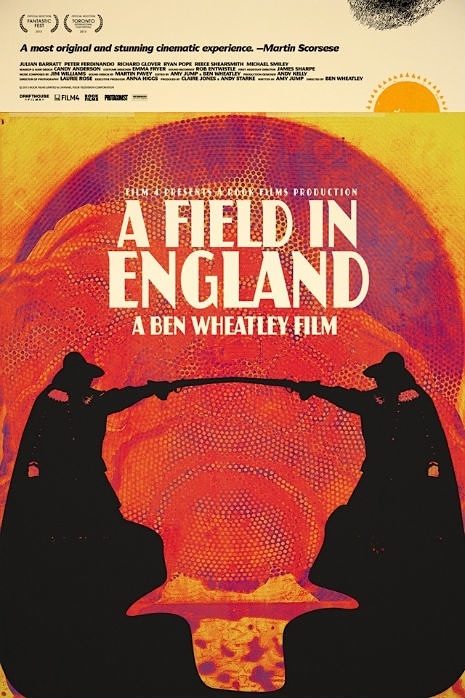

Wheatley’s latest film A Field in England was also written by Jump, and together this highly talented duo have created an intelligent head trip, a radical genre-bender, that mixes alchemy and the occult, with history, horror, psychedelia and folk tales. Starring The League of Gentleman‘s Reece Shearsmith, along with Peter Ferdinando, Richard Glover, Ryan Pope, and a terrifying Michael Smiley, A Field in England is certainly one of the best films of 2013-14.

Without giving too much away, the movie centers around four men escaping from a battle during the English Civil War (1642-1651), when the forces of democracy or Parliament (the Roundheads) fought against the Royalist armies (the Cavaliers) for control of England. The main players in this war were the Cavalier, King Charles I and the Roundhead, Oliver Cromwell, and the poor canon fodder in-between.

Wheatley’s interest in this momentous period of English history came through his work with the Sealed Knot Society, a group of individuals who specialize in reconstructing battles from the English Civil War.

But don’t be fooled, A Field in England is not just a film about the consequences of war, it’s about much, much more.

Last week, I spoke to Ben over the ‘phone about A Field in England. He is currently in Wales, directing the next series of Doctor Who starring Peter Capaldi. I began by asking Ben about the background to his film, and how it had all come about?

Ben Wheatley: “The Civil War stuff had come from my connections to the Sealed Knot Society, I’d wanted to do a documentary about them from a purely selfish point of view I’d wanted to direct a load of big battle scenes, but I didn’t have any money, and I thought if I got involved with them I’d be able to do that. This was in the nineties, and in the end I directed a recruitment video for them and got to marshall thousands of people around, which was just brilliant.

“Dealing with them it kind of rubbed off on me a bit as it was a period of history I didn’t know much about, or had study at school. So, I started reading up on it and found it really fascinating. It’s a period of history that’s not touched on that much. I think maybe because Cromwell is such a fucking difficult character.

“On the one hand it’s about the idea of destroying the monarchy and taking control of the country and giving powers to parliament. Then on the other hand, there’s all the atrocities in Ireland, and the population in the UK was still very Royalist. So the idea of a hero that wants to execute the King is not something they really want to get behind. He’s too problematic, it’s not a black-and-white thing.

“But for me, if anything that’s come out of this island of use in Western civilization are the English Civil War, which is (as far as I can see) the beginning of modern democracy, and the Industrial Revolution, which have affected the world. That’s it. When you get in to it, at that point anything could have happened, as the country was a kind of blank slate—they didn’t know way it was going to go.

“Out of this came the forming of the banking system, modern finance, and also the separation of religion: Christianity, Paganism, and Science, so that was a melting pot of the modern world. I saw it as a starting point, and I saw it also as a starting point for all my other stories, all the other movies that I’ve made. We’re still dealing with the consequences of that moment.”

Dangerous Minds: Your film is open to various interpretations, was this deliberate?

Ben Wheatley: “I think that part of the experience of this film is thinking, is analyzing, and feeling you’re being dropped in an alien culture and you’re trying to work out what the hell’s going on, and I think that is good.

“I think that there’s too much reliance and importance put on clarity of narrative and that everything is absolutely explained all the time, I think certainly there’s a place for that kind of cinema, but I don’t think it should be the dominant form.

“I think that has come out of this culture of self-help, you know script books seem to me to be written in a way that it’s like stories written by accountants—everything has to have it place, everything has to mean something, it’s very specific, there should be no ambiguity about what something means, ambiguity is bad everything wants to be like the Second World War, or Cowboys and Indians, isn’t it? These things are not clear, and life is not like that, it’s much more complex and ambiguous and difficult, and that interests me more.”

Reece Shearsmith gives a brilliant performance as Whitehead.

All of the cast in A Field in England are exceptional—in particular Shearsmith, who is quite incredible, while Smiley confirms his power as an actor—and I wanted to know how Ben had cast the film?

Ben Wheatley: “The casting is similar to the other films I’ve done, everybody in it I’ve worked with before, pretty much, except for Julian Barratt and Peter Ferdinando I’d not worked with on screen before but I know him pretty well and I’d done a lot of read-throughs on other scripts we’d been working on, and I’d seen his movies, which were fantastic.

“Reece Shearsmith I’ve been in contact with and he’s reached out to me through my agent, and I had a couple of meetings with him, and really liked him, and I love his work—I’m a massive fan of League of Gentlemen, and Amy’s a big fan of his as well. And we thought, if Reece wants to do something, we’ll write something for him and see what happens. So, that was it really.

“Then once we put it together you’ve got more chance of getting a decent performance from people that you know, in the way that you couch the characters to them, to make them fit rather than them having to bring this performance thing to it. There’s a sensitivity in the writing that you’re not going to push them into shapes they can’t do. And I think that’s true of all the other movies as well.

“Kill List came about in a very similar way, in that it was a film created with casting—I wanted to make a film with [Michael] Smiley and Neil Maskell, and I also like MyAnna Buring. We tried to work out what their relationship would be, and who they would be, and how that would work, and out of that pot comes what if they were this, and then this happens to them, and it grows out of that. Field was a bit like that, the main consideration was going to be Civil War, and we wanted to set it in a field—it was as simple as that. There would be a boundary in the same way in Dogville there’s this vision at the top of how Dogville is going to work. Other versions of the script were set in a wood, and I wanted to get away from that as it was too similar to the other movies like Kill List and Down Terrace in a way.”

DM: Were there any constraints with filming?

Ben Wheatley: “We were very lucky, because I’ve come from a very low budget background, we made the film in such a…It was written to be made for not very much money to start with, so once you’ve got that, you’ve got that freedom, then really the things that hold back other movies are not necessarily the talent involved it’s more the financial constraints, restrictions.

“If you take £5-million off someone you better fucking get it back or you’re not going to make another movie for a long time. So, if we had made that film and it cost two million quid, we would have been fucked. I think that was the thing. Once we could bring it in under, I mean the budget is as much as a half-hour of TV, of quite low budget TV drama.

“Once we were allowed to do that, we could prove we could do that, we’ve got a good track record, none of our films has gone over budget, and they’ve always come in on time, made on time, post, you know, we delivered it with no major cock-ups, so Film 4 trusted us to make this movie and part of that was that we would have creative freedom on it, and with that creative freedom you can stamp it heavily with authorship.

“Even in the edit they saw, we tend not to show anyone rough cuts, there was no assemble edits shown, so to anyone we show the movie complete, with a mix and a grade on it, and all the effects in place. When [Film] 4 saw it they were like, ‘Here’s some notes, do you want to..’ and I discussed with them, ‘No, not really.’ Like we changed a couple of tiny things in it. That way is the purest. I mean the purest kind of film-making is that you pay for it yourself, you do what you fucking want, no one talked to us about that.

“It kind of depends on what you kind of see as success—success going to Hollywood and doing some massive movie, or is it having complete creative control over a project that people will enjoy watching afterwards. The most pleasure you can have out of stuff is creative control.”

DM: Which directors or films have been influential on you as a film-maker?

Ben Wheatley: “The films of [Ken] Russell, [Nic] Roeg, and [Lindsay] Anderson, and [Tony] Richardson, and [John] Boorman, I love their movies, and I love American cinema, and the French New Wave, and Japanese cinema, Kurosawa. It’s a big broad church of influences, but I think that all goes out the window when you try to make something, because the fight is between, the material and the camera. David Cronenberg said you just deal with it a shot at a time, you just try to make them all as good as can be, because it’s a tunnel vision once you start making stuff, it just closes round you.

“I think it’s different for different films. Kill List was done with having three-or-four key images that I wanted to shoot, and then working around Down Terrace was one image, then Sightseers was experiencing it, just rolling with it and seeing what happened. A Field in England was a bit more specific, though it was still made-up on the spot—you have to.

“The process, my experience of it is like drawing or painting, you know, you go into a kind of state of mind where you can see it like a vision. I know that’s the cliche—the director’s vision—but it literally is a vision, you know. You hold your hand over your face and you watch the film, and then you go and shoot a little bit of it, and

you keep doing that again-and-again, but that can only be done on set because planning ahead of time you bend the environment to your will—you imagine the actors doing it in a certain way, you force them into it, and when you get there it’s totally different, so it has to be done on the spot really.

“I do storyboard a lot, and I draw a lot, and plan a lot, but none of it is that useful in the end, you know, because there are other constraints. If the scene is scheduled at the end of the day, then that scene is going to get shot than one in the morning, that’s just the way it is. If you over complicate, you’re not going to get to do it. You need to be dynamic all the time and changing it, and cutting your cloth accordingly. Something like Doctor Who, we storyboarded absolutely every frame of it, and I don’t think I’ve looked at the storyboards till we started shooting, just because there’s too much going on.”

DM: What are you working on now, and what’s next?

Ben Wheatley: “I’m shooting Doctor Who at the moment and then the next film I’m doing is J. G. Ballard’s High Rise. That’s happening in July, I think, and that’s all ready to go.”

‘A Field in England’ is in cinemas now, or can be watched from Drafthouse Films here.