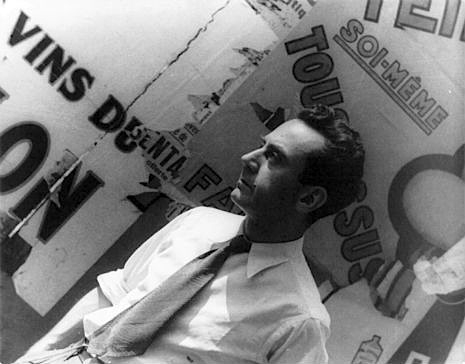

Apart from his glittering career as a photographer, painter and “maker of Surreal objects,” the American artist Man Ray was also a filmmaker of considerable skill and originality.

Born Emmanuel Radnitzky in Pennsylvania on August 27th, 1890, Man Ray was the first of four children born to Russian immigrants. When he was seven, the family moved to Brooklyn where he shortened his first name from “Manny” to “Man” and because of the anti-semitism rife in New York at the time, the family changed their surname from Radnitzky to Ray—hence Manny Radnitzky became “Man Ray.” From an early age he assisted his parents with their work in the garment trade—his father was a tailor, his mother made simple designs—and it was hoped the eldest son Manny would follow in the family business. But Man Ray had other ambitions and he taught himself to draw by spending time in museums and art galleries, and eventually won a scholarship to study architecture, but he rejected it in favor of being an artist. This decision was confirmed for Man Ray after he saw the Armory Show in New York, 1913.

In 1915, Man Ray had his first solo exhibition. He then decided he wanted to be a part of Dada—the “anti-art movement” to this end he became friends with Marcel Duchamps, and the pair worked together on early examples of kinetic art.

In 1921, Man Ray moved to Paris, where he lived in the artists’s quarter of Montparnasse, and fell in love with the famous model, singer, budding actress and well-known Bohemian Kiki de Montparnasse (aka Alice Prin). Kiki became Man Ray’s lover and muse, who he began to photograph, which in turn led him to his first experiment as filmmaker Le Retour à la Raison in 1923.

Man Ray aligned himself with the Cinéma pur movement, which focussed on taking film away from narrative and plot and returning it to movement and image. Its proponents were René Clair, Fernand Léger, Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling, amongst others, and their short films were the beginnings of what was to become “Art Cinema.”

Adhering to Cinéma pur‘s loose manifesto, Man Ray’s early films, Le Retour à la Raison (Return to Reason) in 1923 and Emak-Bakia (Leave me alone) in 1926, focussed on creating startling textural patterns through the representation of objects within rhythmical loops. The experimentation of Le Retour à la Raison was repeated and developed in Emak-Bakia, and many of the techniques Man Ray developed (double exposure, Rayographs and soft focus) were later co-opted by animators and filmmakers during the 1940s to 1960s.

‘Le Retour à la Raison’ (‘Return to Reason’)

‘Emak-Bakia’ (‘Leave me alone’)

Moving away from Cinéma pur, Man Ray began to experiment with narrative structures and dramatic sequences. In L’Étoile de mer (The Sea Star) 1928, he told the story of two lovers from the point of view of an (underwater) starfish. The story had been inspired by a friend who kept a starfish in a jar by their bedside, and was written by the poet Robert Desnos, who tragically later died in a concentration camp in 1945.

The film starred Kiki de Montparnasse, Desnos and André de la Rivière, and was a mix of Surreal poetry and dreamlike visuals that almost seem to promise more than they deliver. The film begins with the lines:

Les dents des femmes sont des objets si charmants… (Women’s teeth are such charming things…)

And continues with such lines as:

Les murs de la Santé (The walls of the Santé)

Et si tu trouves sur cette terre une femme à l’amour sincère… (And if you find on this earth a woman whose love is true…)

Belle comme une fleur de feu (Beautiful like a flower of fire)

Le soleil, un pied à l’étrier, niche un rossignol dans un voile de crêpe. (The sun, one foot in the stirrup, nestles a nightingale in a mourning veil.)

Before ending:

Qu’elle était belle (How beautiful she was)

Qu’elle est belle (How beautiful she is)

Which brings the film, and the relationship, to a close.

‘L’Étoile de mer’ (‘The Sea Star’)

Man Ray’s longest film Les Mystères du Château de Dé (The Mysteries of the Chateau of Dice) in 1929 followed the visit of two travelers to the Villa Noailles in Hyères—the home of husband and wife Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, the highly significant patrons for Picasso, Cocteau, Dali, and many of the Surrealists. The film is Surreal, dreamlike, and has been described as “an architectural document…inspired by the poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé.”

The poem referenced was “Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Abolira Le Hasard” (“A Throw of the Dice will Never Abolish Chance”), written by Mallarmé in 1897 and published over twenty pages in various typeface and structure. It contained early examples of Concrete Poetry, free verse and presented highly innovative graphic design that would later influence Dada. The poem can be read here.

Les Mystères du Château de Dé was Man Ray’s longest film at 27 minutes.