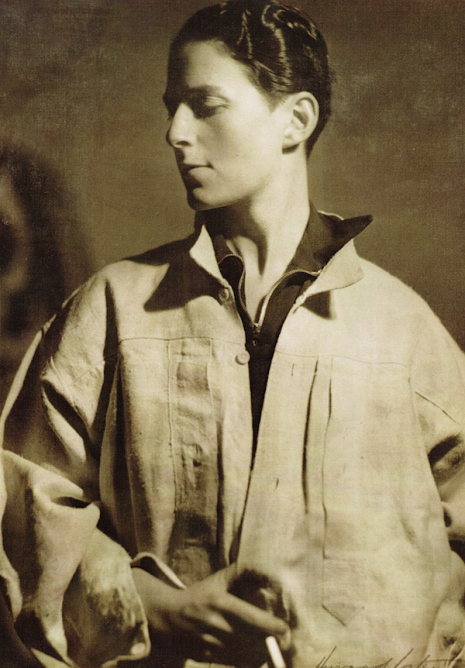

Gluck, circa 1924.

Hannah Gluckstein preferred to be called Peter or Hig but liked “Gluck, no prefix, suffix or quotes” best. Gluck. A functional name. Gender neutral long before such a term existed. A trademark, a product, a producer of art.

Gluck was born into a very wealthy Jewish family on August 13th, 1895 in London. The first born, a daughter who was expected to grow happy and demure and marry a most suitable husband—someone who would make the family proud and strengthen the business. But that wasn’t Gluck. Early photographs show a long-haired girl staring fixedly at the camera with defiance and dreams of another life.

This life came with a growing interest in painting and drawing and a desire to be an artist. The family were not impressed. The Glucksteins were half of the business empire Salmon & Gluckstein, owners of (what was claimed to be) the world’s largest tobacco company, a selection of hotels (the Cumberland, the Trocadero), and the famous Lyon’s Corner House tearooms, which were a staple of British social life from the 1920s-50s—see Graham Greene’s novels for details. Art was a poor choice for business and a not a suitable career for a woman. Yet, Gluck’s parents indulged their daughter thinking this trifling passion for art was mere whimsy, a passing phase.

Between 1913-1916, Gluck attended the St. John’s Wood School of Art in London. The parents hoped this experience would cause Gluck to give up on this teenage fancy. Instead it proved to be three years that changed Gluck’s life and confirmed a startling talent and some deeply held ambitions. At the college, Gluck met another artist Miss E. M. Craig, a mysterious figure who was simply known as Craig. Together they eloped to Lamorna, Cornwall to an artists’ colony. Gluck’s parents were shocked. This was not the kind of thing a good Jewish girl was supposed to do. They blamed Craig as a “pernicious influence.”

Yet still, when their wayward daughter reached the age of 21, Gluck’s father supplied a trust fund which ably supported the move to Cornwall, where Gluck bought a studio. The money also enabled Gluck to be the person little Hannah Gluckstein had once dreamed of becoming. Hair razor cut like a boy’s, a suit handmade by one of London’s finest tailors, and the adopting of the name “Gluck.”

Gluck was particular about this new name. People who used any other name, any former name, were cut off. Once, an art society sent a letter to “Miss Gluck”—Gluck resigned from the society immediately. It led many to describe Gluck as “a difficult woman.” Now Gluck was free to begin a new life.

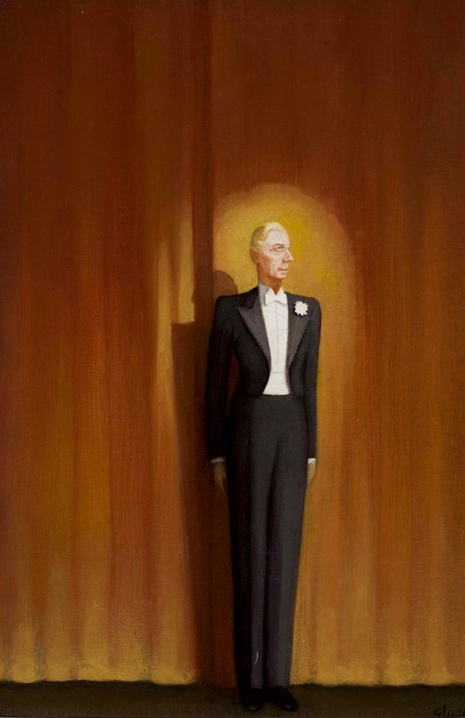

In the 1920s, Gluck held a first “one man exhibition” of diverse artworks. It brought celebrity and commissions to paint portraits of the elite members of the establishment—lawyers, judges, and so forth. The solo exhibition was visited by members of royalty and politics, and brought contacts with some of society’s most influential enablers. The interior designer, Syrie Maugham, wife of writer Somerset Maugham, used Gluck’s paintings to enhance her creations which brought further fame and more commissions.

When Gluck’s father died in 1930, it was the younger brother who inherited the estate as the eldest male heir. This (understandably) proved to be an irksome bone of contention which meant Gluck had to ask, or go cap in hand, for any further monies. Yet, if Gluck had wanted to be truly independent then it would have made far more sense to cut all ties with the family and establish a career by hard work and perseverance. But the family’s wealth allowed Gluck to live a life of luxury, to live the life of an artist, or as Picasso once almost poetically put it—to be rich enough to live poor.

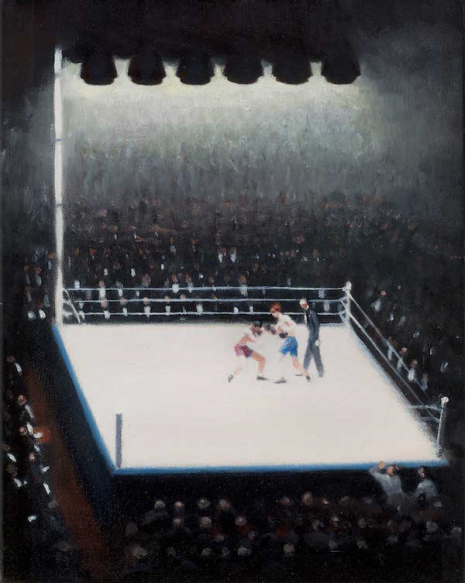

Money was important but a more important factor in Gluck’s development as an artist were the women who became lovers. One was Sybil Cookson, the journalist and writer who inspired Gluck’s paintings of horse races and boxing matches. The couple lived together at Bolton House in West Hampstead, bought by Gluck’s father and maintained by a staff of servants—a cook, a maid, and a housekeeper. The relationship between the two women lasted until Cookson caught Gluck frolicking with a dancer called Annette Mills, who was the actor John Mills older sister and was later famous as the presenter of the classic BBC children’s show Muffin the Mule (which perhaps brings a whole new meaning to the term “Muffin the Mule.”) This fling lasted until Gluck formed a new relationship with the florist and flower arranger Constance Spry who inspired Gluck’s sequence of exquisite floral paintings. This revelation of the secret relationship between Gluck and the married Spry only became public after Diana Souhami published her excellent biography on the artist in 1988—a book and a writer whose work I thoroughly recommend to all.

But the woman who brought Gluck to the height of artistic expression as a genderqueer icon was Nesta Obermer, an American who was married to an older, exceedingly rich Mr. Moneybags. Gluck fell deeply, passionately in love with Obermer and wanted to live with her “for eternity.” Gluck took the title husband and called Obermer wife. Gluck was so convinced this was the beginning of a bright and beautiful future together that old photographs, letters, and even paintings were burned as a symbol of this new beginning. Their marriage was confirmed in the painting “Medallion” or “YouWe” in 1936. A powerful portrait of an out lesbian couple or as Gluck described it in a letter to Nesta:

Now it is out and to the rest of the Universe I call Beware! Beware! We are not to be trifled with.

The two women in profile. Gluck the darker more pessimistic looking. The blonde-highlighted Obermer head up, eyes glinting to a better, brighter future.

And there was the rub.

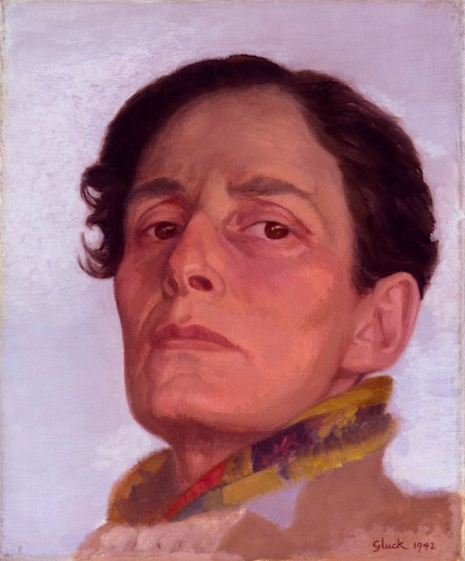

If Gluck and Obermer married what sort of future would it be? How would they live? Obermer was not entirely smitten to cede the comfort and wealth of her rich aged beau, no matter how little she thought of him. She could never give up the lifestyle to which she had become accustomed. The relationship lasted six years. When Obermer left, Gluck was devastated—as can be seen in the powerful “Self-Portrait” from 1942, which depicts Gluck looking almost as if recently bereaved and bravely attempting to carry on alone.

Alas, Gluck did not carry on. The work faltered, and years were spent in correspondence with paint companies attempting to find better quality paints for artists. Worthwhile, yes, but not a subject to consume a talent as rare and as brilliant as Gluck’s.

After the Second World War, Gluck fell out of favor as an artist. A new world of Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art dominated. In 1973, over thirty years since the last solo exhibition, Gluck held a final exhibition at the Fine Art Gallery. It was a last hurrah for this pioneering and distinctly unique talent. One of Gluck’s last paintings “Credo (Rage Rage Against the Dying of the Light)” (1970-73) captured the artist countering the inevitable decline:

I am living daily with death and decay, and it is beautiful and calming. All order is lost; mechanics have gone overboard—A phantasmagoric irrelevance links shapes and matter. A new world evolves with increasingly energy and freedom soon to be invisibly reborn within our airy envelope.

Gluck died at the age of 82 on January 10th, 1978.

‘Portrait of Miss E.M. Craig’ (1920).

‘Gluck. Before the races, St Buryan, Cornwall’ (1924).

‘Ernest Thesiger’ (1925-6).

‘Baldock vs. Bell at the Royal Albert Hall’ (1927).

‘Portrait of Miss Margaret Watts’ (1932).

‘The Devil’s Altar’ (1934).

‘Lillies’ (1932-6).

‘Lords and Ladies’ (1936).

‘Medallion’ (‘YouWe’) (1936).

‘Self Portrait’ (1942).

‘Requiem’ (1964).

‘Credo (Rage Rage Against the Dying of the Light)’ (1970-3).

H/T Guardian.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

The ‘private’ photographs of Marie Høeg and Bolette Berg: Questioning gender roles circa 1900

Marianne Breslauer’s gorgeous photos of queer, androgynous and butch women of the 1930s

Vampire Lesbians of Hammer

Lesbians React to Lesbian Porn (Priceless and slightly NSFW-ish)

‘Because We’re Queer’ - The Life and Crimes of Joe Orton

Radical queer photographer documents S & M culture in ‘family photos’

Disturbingly lifelike gender-bending mannequins