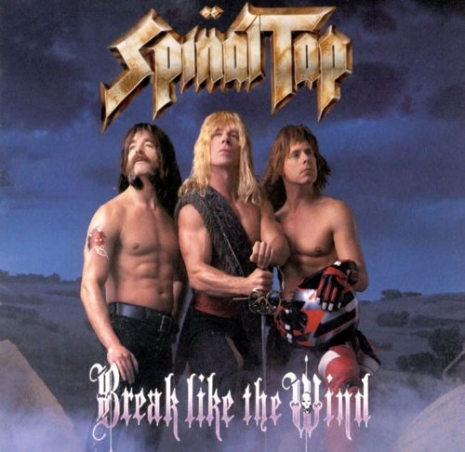

Walter Becker passed away last weekend. I’ve been listening to Steely Dan a ton all summer long, so the loss hit a little harder than usual. The news elicited the usual round of condolences and encomiums from fans across the world, a group that included one that maybe Becker’s fans weren’t waiting for as much. Michael McKean, lately killing it in Better Call Saul and of course (as David St. Hubbins) the lead singer of the world’s most preposterous heavy metal band, Spinal Tap, reminded his Twitter audience that Tap and the Dan did indeed once cross paths:

A dollop of Walter Becker genius. Tap asked him to write a little something technical re BREAK LIKE THE WIND & he did. pic.twitter.com/DX8XPz4Oo3

— Michael McKean (@MJMcKean) September 3, 2017

Michael McKean is probably the most musically gifted of the Spinal Tap guys—remember, he was once briefly a member of an actual band, namely the Left Banke, and his father was one of the co-founders of Decca Records. So on some level it makes sense that he would be the one to think of including Walter Becker in Spinal Tap’s 1992 album Break Like the Wind in the form of some silly-ass “technical notes.” That album was quite a star-studded affair, in fact, featuring the contributions of Jeff Beck, Dweezil Zappa, Joe Satriani, Slash, and Cher. I’m betting McKean was on the phone a lot that year.

Becker’s notes make up one “panel” of the fold-out lyrics sheet on the CD release. You can see a picture of the whole shebang on the Australian CD release. The entirety of Becker’s account of “the astonishing Crosley Phase Linear Ionic Induction Voice Processor System” runs exactly four paragraphs, in which space Becker earnestly touts the invention of one “Graehame Crosley” which functions by “measuring “the flow of ionic muons” from the singer’s vocal output, for which the singer is obliged to “wear on his person a number of small balance plates which will offset the fields created by various inanimate objects on his body at the time of the recording.” The duly muon-measured vocal stream, in the case of this album, was then captured on “the huge BBC 16 channel cassette recorder which the band had schlepped over from David’s home studio.”

Not surprisingly, Becker absolutely nails the particular tedium and self-importance familiar to anyone who has perused such technical accounts on album liner notes, but was careful to sprinkle in a few unmissable gags to get the sought-after chuckles from Tap’s fan base. But this would not be a Steely Dan story if there weren’t some grousing and bad feeling somewhere. In the April 1992 issue of Metal Leg, the exhaustive Steely Dan newsletter that existed from 1987 through 1994, Becker wrote an account of submitting those “technical notes” to the Tap crew. His primary contact was “Mike McKeon” (sic), and according to Becker, Spinal Tap wanted Becker’s text primarily for use “in a throwaway fashion, more as a design element than anything else”—which seems rather unlikely when you think about it, you don’t go to Walter Fucking Becker for the equivalent of musical lorem Ipsum text. But Becker was “perhaps erring on the optimistic side insofar as a good outcome was concerned” because the Spinal Tap guys pared down Becker’s text somewhat, indeed omitting an entire paragraph dedicated to an account of dealing with the Crosley System’s inability to deal with a vocalist who had previously undergone a brass kidney transplant (this being Derek Smalls).

Having his text fucked with in this manner seems to have really set Becker off, who tetchily informs Metal Leg that by being able

to set the record straight, I feel that I may yet snatch victory from the clutches of disaster, especially since your circulation may well exceed the sales of the doleful Tap disc, once we correct for the high percentage of non-readers or remedial readers in the ranks of Tap purchasers, many of whom bought the CD by mistake anyway, thinking it was either a) an actual heavy metal album, or b) funny.

Whoa! All you angels up there in heaven, do make sure to not get on Walter Becker’s bad side!

It could be that this minor conflict, such as it is, explains Becker’s noticeable omission from the album’s list of thanked people (the five guest musicians mentioned above all got thanked).

For lack of any better video to showcase, here’s the video for “Bitch School,” the second single off of Break Like the Wind”:

Here’s Becker’s introductory message to Metal Leg; the “Pete” refers to Pete Fogel, one of the editors of Metal Leg—Becker rags on him too, don’t worry, but in more of a loving vein.

Dear Pete,

Just because I pretend not to know who you are as often as not on those rare occasions when I see you, usually in New York at a Rock and Soul gig or some such thing, or because I have not in the past responded to certain requests that have been received by me however indirectly, from you or from your pal Brian Sweet, who it must be admitted was most accommodating in sending me all those years’ worth of clippings from his copious Steely Dan scrapbook; this does not mean that I am in any way unaware or even perhaps unappreciative of your splendid efforts through the years on behalf of the loyal fandom of the mighty Steely Dan, particularly of your extraordinary tact and discretion in not contacting me or mailing material to me at my home in Hawaii or for that matter anywhere else, considering that my address and my whereabouts at any given time are surely known to you and your confederates — for all of this and for other considerations which I won’t go into at this time, I say “thanks” and hold out to you, symbolically as it were, the hearty handclasp of friendship. And as a token of my not-unappreciativeness I am offering you for publication in your little mag the complete unedited version of the liner notes which I wrote for the late Spinal Tap “Break Like the Wind” album. As you will I am sure agree, even a casual comparison with the original reveals that the version which appears in the CD itself has been edited to remove all of the good parts — and why such a thing has come to pass, I myself cannot say. When I was approached by Mike McKeon, he told me that the notes would be used in a throwaway fashion, more as a design element than anything else, and that their legibility would perhaps be nil; I told him I would try to make them amusing nonetheless and that he would be free to edit them as necessary to conform to their layout. By putting my trust in the Tap gang’s innate sense of what was amusing and what would work best for their overall concept I was perhaps erring on the optimistic side insofar as a good outcome was concerned; this lesson has not been lost on me and, what is more, by availing myself of your good offices so as to set the record straight, I feel that I may yet snatch victory from the clutches of disaster, especially since your circulation may well exceed the sales of the doleful Tap disc, once we correct for the high percentage of non-readers or remedial readers in the ranks of Tap purchasers, many of whom bought the CD by mistake anyway, thinking it was either a) an actual heavy metal album, or b) funny.

In any event, I am hoping that the publication of the original (unedited, and in conjunction with this note) will serve to educate and entertain your readers in a way that meets with your editorial approval. If not, feel free to toss the whole enchilada into the trash — in which case it may well end up in close physical juxtaposition to one of the countless Tap CDs or cassettes that are currently clogging up landfills all over this great nation of ours.

Yours,

Walter Becker

And Becker’s shaggier original submission to Spinal Tap:

Spinal Tap Technical Notes

Remarkable as this recording may be on the esthetic level, it so happens that “Break Like the Wind” is equally notable for its breakthroughs in the state of the art of modem audio recording techniques. Let me explain.Firstly, all of the vocals on the current album were recorded and re-mixed with the astonishing Crosley Phase Linear Ionic Induction Voice Processor System. This device was invented and first used by the late Graehham Crosley and was later perfected for studio use by producer Reg Thorpe, who had an aborted go with the Tap lads during one of their early mid-seventies comeback attempts. There were a few bugs in the system at that time (“Like, it wouldn’t fucking work. Period.” recalls Nigel Tufnel fondly) and so work with it was abandoned. In the intervening years Thorpe has managed to sort out the last remaining kinks in the system and made it available for these sessions. He himself generously offered to make the crucial fine adjustments necessary to eliminate background chatter and allow the awesome fidelity and signal to noise ratio of The System to stand out, as I believe it does, in the final mixes.

Here’s how the Crosley device works: when a vocalist sings, a stream of accelerated air particles issue from his vocal chords, out his mouth and out into the room where there is waiting, we hope, the diaphragm of an expensive tube mic. This diaphragm does a passable job of imitating the vibration of the air molecules by twitching in its little suspension, which movements are we hope turned into a low level electrical flux in the tiny wires attached to the diaphragm assembly. But wait! For there are many problems inherent in a device of this sort, including mechanical resonances in the diaphragm itself, variations in the temperature and humidity of the air in the room, foreign particles issuing from the gaping maw of the vocalist himself (a particular problem for the Tap lads — corrosive smoke particles and bits of mango pickle from cheap Indian takeaways) and so on, all of which result in reduced fidelity for you, the listener. However, the Crosley device does not care one whit about all of these things, for it measures only the flow of ionic muons (small charged particles with an atomic weight of between 1.699669 x 10 -17 Electron Units and roughly twice that much, give or take a teenie bit here and there) past a negatively charged grid, itself roughly the size of, say, a gnat’s cock (to use a comparison to which most of us can relate). The resulting current is used to modulate a constant voltage which is self-referenced to the known inductance of the system itself and to the body capacitance of The Artist. For in order for the system to work, the vocalist must wear on his person a number of small balance plates which will offset the fields created by various inanimate objects on his body at the time of the recording (afterwards he may wear what he likes). In the case of David St. Hubbins for example, after much experimentation the correct voltages were found to be applied to these small balancing plates when attached to his billfold, to his wristwatch (a fake Rolex which he evidently took for the real thing), and to the Raybans that he habitually wore in the studio (“Me lucky shades”). It was also necessary to put a plate in his groin region to offset the charge produced by, of all things, a roll of quarters tucked into his shorts. This combination — spectacles, testicles, wallet, watch — seemed to do the trick and soon enough a frighteningly realistic and three dimensional vocal image was suspended in space between the nearfields mounted on the console (Wombat G 7’s and Holographe 96/96, respectively).

Derek Small presented a somewhat more difficult challenge. After several failed attempts to get the system to work, Derek recalled that he had had a kidney operation back in the mid-sixties which had resulted in the installation of a brass kidney. This was evidently an experimental treatment which the national health abandoned after only a few tries, Derek being one of the unfortunate guinea pigs. It was necessary to install a plate, therefore, in one of Derek’s body cavities. Ears, nose and throat were obviously not available, Derek adamantly’ refused to accept catheterization, and in the end the necessary balance plate had to be installed — rectally. Derek resisted this onerous procedure at first and the whole Crosley gambit seemed as though it might fail, but like a true Englishman, Derek eventually agreed to compromise his personal comfort somewhat so that the team effort might succeed. I can only add that Derek ultimately came to tolerate well, if not actually enjoy, the daily installation and retrieval of the balance plate, and that in the process it was discovered by Ronnie, one of the second engineers at the studio and the individual charged with performing these delicate operations, that a) Derek’s prostate was enlarged to the approximate size of a grapefruit, and b) Ronnie’s engagement to Kimberly, the studio receptionist, was perhaps a bit premature.

The feed from the Crosley system was now presenting us with a glorious soundstage recreation of the band’s vocals. This was mixed in with the roar of the band’s amps and drums (so loud that mic’s were not necessary) and fed to the inputs of the huge BBC 16 channel cassette recorder which the band had schlepped over from David’s home studio. This machine (affectionately nick-named “The Beast”) was based on a design found in Hitler’s bunker at the end of the war and its sound quality, in the opinion of many recording artists, has never been equaled. This was then mixed down to acetate and bunged over to the digital (phooey!) mastering format for cassettes and CDs, in which form it is currently gracing your living room or, more likely, your car, as the case may be.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

Life imitates comedy: Spinal Tap uncannily anticipated Black Sabbath’s very own Stonehenge debacle

Dead to Dan: Steely Dan’s amazing guide to giving up the Grateful Dead and becoming a Steely Dan fan