The playwright David Mercer was born in 1928, in a working class district of Wakefield, in the north of England. He was raised amid the poverty and hardship that bred the instinctual Socialism of his father and uncles, which they had learned from experience, and gathered from books by Wells, Shaw, Lenin and Marx. This was Mercer’s first taste of the politics, handed-down, father-to-son, which was to influence all of his writing.

He quit school at 14, and worked as an apprentice technician, before he signed-on for 4-years with the Royal Navy. He went on to study at King’s College, Newcastle, then married and moved to Paris, where he tried his hand as an artist, before deciding he was best suited at being a writer. He started out by writing long, rambling novels greatly influenced by Wyndham-Lewis. The practice taught him he could writer, but his novels were too abstract and had no relation to how he truly felt. This taught him that he could write but was not a novelist, he therefore started writing plays.

His first Where the Difference Begins (1961) was originally intended for the stage, but was produced for television by the BBC. The play was a valediction to the old men of Socialism, the Keir Hardie inspired patriarchical socialism being left behind by the active Marxism of a younger generation. The play reflected the difference between his father’s beliefs and Mercer’s own—though Mercer was smart enough to be critical of his own ideals.

The play was successful and he followed it with A Climate of Fear (1962), which dealt with conscience under the threat of a possible nuclear war, and The Birth of a Private Man (1963), concerning the problems of maintaining strong political conscience within an affluent environment.

Mercer brought a naturalism to the theater of ideas—he discussed issues of Empire, politics and patriarchy in plays such as, The Governor’s Lady (1965) and After Haggerty (1970), while his television plays, The Parachute (1968), which starred fellow playwright John Osborne, and On The Eve of Publication (1969) with an incredible central performance by Leo McKern, and Shooting the Chandelier (1977) with Alun Armstrong and Edward Fox, which have shaped TV drama right through to present day (in particular the works of Stephen Poliakoff or David Hare), though David Mercer himself is all too often forgotten.

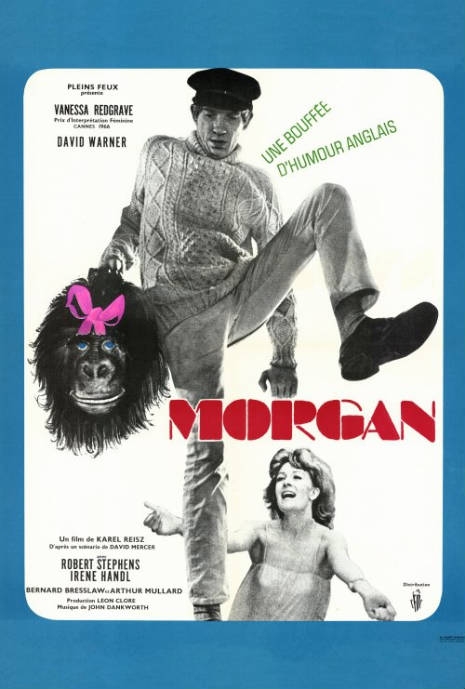

Though a Socialist, Mercer was never blinkered to the follies and mistakes of Socialism, Communism and the politics of the Left. He was aware that the aim of political revolution was often frustrated by the inherited conventions of society, and by the frailty of human emotion and mind. This was shown to it great effect in the film version of his play, Morgan: A Suitable Case for Treatment (1966), in which David Warner, had an obsessional relationship with Marxism, apes, and his ex-wife (Vanessa Redgrave), that led him to (literally) become a revolutionary “gorilla” determined to derail his ex-wife’s new relationship.

Through his intelligent, funny, emotionally satisfying dramas, Mercer was able to bring serious political debate to the heart of theater, as he said in an interview to the BBC about his screenplay Providence for Alain Resnais, in September, 1978:

‘I regard the theater as being a place where language is of the highest importance. Theater is the place where perhaps the values and the use of language have the greatest impact.

‘At the same time, these questions have also complicated and—often issues of political controversy and contradiction—intellectually complicated matters. It absolutely impossible to simply dramatize a subject like this, except in a direct way, where people come out in the open and say what has to be said.’

And it was what Mercer said that often led him to be reviled by the Left and the Right, as either betraying Socialist ideals, or preaching Communism. Yet, Mercer was too much a rational Humanist to be swayed by any party line. His belief was ultimately in humanity.

‘One of the things that absolutely lifts me up and revives me always is the reality of human courage, and the reality of human resistance to oppression. If you like the human tendency to anarchy—at a simpler level to sheer bloody-mindedness. The refusal of human beings simply to be the object of political or other kinds of control.

‘In this play, someone makes a very difficult and courageous decision, and it’s this which I respect an awful lot, in people in general. And people who live in authoritarian societies in particular, I am absolutely overwhelmed by their heroism and their willingness to risk their lives, their careers, and so on, for the sake of their convictions, political, moral or otherwise.

‘No one supports more passionately, than I do, the cause of the Soviet dissidents, that is absolutely beyond question. What I am almost equally concerned about is the way dissidence is used in the West, in a way one aspect of Western propaganda in the great ideological war between the Soviet union and the Western World.

‘Now, freedom is very real in the West, whatever Marxists say. there is no such thing as Bourgeois Freedom and Revolutionary Freedom, there is only Freedom, and it is indivisible, and it is absolutely proper and correct to support dissidents in every way we can—that must happen, that has happened, and I’m glad. But what I do resent is the extraordinary silence about much of the barbarism and political immorality going on in the West, to which we don’t pay the same kind of scrupulous attention.’

Mercer died of a heart attack in 1980, while walking through Haifa, Israel. Though undoubtedly some of his output has dated—a recent revival of After Haggerty revealed his view on the world of 1960’s politics to have moved on significantly—but most of Mercer’s work is still relevant, important and influential enough to warrant serious reappraisal, and a re-release in print and on disc.

The first interview clip is from 1978. The second is an exceedingly rare (hence the quality) documentary about Mercer from 1966, which includes a contribution from David Warner.

An in-joke from the clip of Providence reveals Mercer’s humor. The clip has Gielgud discussing the author of a book, presented to him by Bogarde, who he calls “Bumface”. The author photograph on the dust-jacket is, of course, David Mercer.

With thanks to NellyM