A review of John Gray’s new book, The Silence of Animals: On Progress and Other Myths (interview below)

I remember reading John Gray’s epochal Straw Dogs: Thoughts on Humans and Other Animals sometime in 2004, and occasionally laughing out loud at the sheer misery and horror presented therein. Indubitably the book—one of those you’re likely to read not only without putting it down but without blinking—made an exceptional case for the human animal being frail, amoral, savage, irrational and (last but not least) collectively and individually doomed, but as such reading it felt vaguely masochistic, and reading its brilliant successors—from the happy-go-lucky Black Mass to the laugh-a-minute Al Qaeda and What it Means to Be Modern—frankly perverse (like philosophical self-flagellation). One persisted because Gray was so obviously among the finest writers alive—the nearest thing we have to a Nietzsche by a country mile.

Well as it happens, Gray’s new book, The Silence of Animals: On Progress and Other Modern Myths is not merely an exercise in iconoclasm, and finds the author in an altogether different mood, exploring what might be advisable to the human animal whose precarious existence is compounded by an indifferent universe.

An important thing to note here is that Gray’s books were never meant to revel in pessimism, but to warn us away from reckless delusion. Were fatuous optimism harmless, then maybe we would all do well strolling about looking forward to an eternity in heaven, or, alternatively, anticipating the imminent defeat of death, as did some Bolsheviks (which Gray investigated in his last book, The Immortalization Commission). Such giddy dreams, however, tend to come at quite a frightening price, and the Inquisition or Stalin’s terror represent the respective and bloody tips of those particular icebergs.

Furthermore, although he must have savaged a few thousand modern myths in his time, Gray’s objection is not with myth per se. How else, after all, could he or we hope to grasp his work’s guiding equation—in which to attempt to impose or even seriously imagine an existence without suffering and death exponentially multiplies their influence? The myths of Prometheus or the myth Genesis, Gray suggests in The Silence of Animals, are the very medicines needed to treat those modern myths fathered by Socrates and Christ, two martyrs who chucked caution to the wind… and inspired the rest of the species to follow suit.

Now, if we subsequently see Prometheus or Genesis as being “true”—what do we mean by this? Not that they actually occurred, that’s for sure (Gray has pointed out before that it was only recently that Christians started to consider Genesis as being a literal account of human origins). But this eschewal of literalism is not necessarily an eschewal of mysticism. When we use myth as we have done here, we are trying to access something beyond language and even science—story and symbol are all we have.

For the so-called “New Atheists,” on the other hands, nothing exists you can’t just slap a word on, so their “disbelief” is a matter of having the word “God,” but not having an entity to affix it to (they’ve looked everywhere). Gray suggests an altogether more elevated position:

“Atheism does not mean rejecting ‘belief in God.’ It means giving up belief in language as anything other than a practical convenience. The world is not a creation of language, but something that – like the God of the negative theologians – escapes language. Atheism is only a stage on the way to a more far-reaching scepticism.”

The Silence of Animals is a profound exploration of this “far-reaching scepticism”—or “Godless mysticism.” It is also one of Gray’s best books. No mean feat.

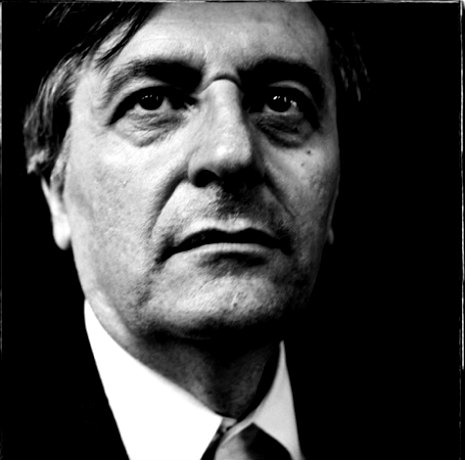

An interview with John Gray

Thomas McGrath: John, how did you conceive of The Silence of Animals? Penguin are calling it “the successor to Straw Dogs”—was this your own conception of the book?

John Gray: I do think of The Silence of Animals as a successor to Straw Dogs, though that only became clear to me as I wrote the book. I began it as an exploration of secular myth, especially the variety in which meaning is embodied in cumulative advance in time, but it soon became an attempt to dig deeper into the themes of the earlier book—in particular the idea of contemplation. The chief difference between the two books, from my point of view, is that by presenting contemplation as correlative to a life of action. The Silence of Animals is more positive in tone.

TM: Your The Immortalization Commission is pervaded by the fascinating spectre of the subliminal self - to what extend do you feel something like this guides your own work?

JG: I wrote The Immortalization Commission for three reasons. First, to show how bizarre the history of ideas actually is—and how different from the cleaned-up version that is commonly accepted. Second, to show how the most far-fetched ideas can become an integral part of life as it’s actually lived. How many people know that Arthur Balfour entered into an imagined posthumous correspondence with someone he may have loved? How many that the embalming of Lenin was part of a larger attempt to conquer death? For the people whose stories are told in the book, overcoming death through science wasn’t just an abstract notion. Thirdly, I wanted to tell a story—two stories in fact, though they overlap and interlink—rather than just set out another argument.

Again, these reasons only became clear while writing the book, so I suppose it is true that my writing is in some degree guided by a subliminal thought-process. Maybe this is true of all writers, whether or not they recognize the fact.

TM: The Silence of Animals seems to me your least iconoclastic work. For the first time, you seem to be exploring how the individual might approach the world as it’s presented in your other books. Is this an accurate interpretation?

JG: The Silence of Animals does flow from my earlier work, and you’re right to say that it tries to show how someone who accepted the view of things presented in my other books might approach the world. I’m not sure it will be seen as less iconoclastic—those who hated my earlier work will also hate this, I’m sure, because it too refuses to take seriously the faith in action and progress that they think they live by.

TM: From The Silence of Animals: “By creating the expectation of a radical alteration in human affairs, Christianity—the religion that St Paul invented from Jesus’ life and sayings—founded the modern world.” Given that this “expectation” is the very thing you diagnose as lying behind all the Utopian mythologies you attack, to what extent do you view Christianity as a pivotal and essentially detrimental emergence in the history of humankind?

JG: I think of Christianity as being like many world-transforming movements—at once extremely harmful and highly beneficial. Either way it marks what you call a pivotal point in history. Christian myth seems to me deep and interesting, at times also beautiful, whereas the myths of its secular successors strike me as shallow, banal and ugly.

TM: This critique of Christianity’s influence on humanity resembles Nietzsche’s—especially since you see its influence as allied with Socrates’. I’m interested in your relationship to Nietzsche. It’s obvious how you differ, but was he quite formative to your worldview?

JG: Nietzsche was a gifted moral psychologist from whose writings I’ve learnt a great deal. As you can see from my response above, I don’t share his outright condemnation of Christianity. He was in fact much more confined by a Christian world-view than Schopenhauer, an early and powerful influence on him. The later Nietzsche—who became a sort of hyper-humanist—I find absurd, though still more interesting than the dull, respectable, neo-Christian humanists of today.

TM: One way you distinctly differ from Nietzsche is on the matter of morality. Indeed, in The Silence of Animals you describe slavery and torture as “universal evils.” As a reader, however, I feel I know very little about your views on ethics and morality, or the philosophical foundation for such a statement. How would you define your moral philosophy? Do you, perhaps, have this in mind for a future work?

JG: You are right that I differ from Nietzsche in thinking there are universal evils such as slavery and torture. You’re also right that I intend to focus on ethics in future work—more specifically, I’m thinking of writing a post-Nietzschean genealogy of morals.

TM: You like telling stories about intellectuals. What events in your own life were pivotal to your worldview?

JG: I don’t think any single event has shaped my thinking. I was influenced by the collapse of communism—a development viewed by mainstream opinion as beyond the realm of reasonable probability, but which I thought quite likely from the early eighties onwards. The financial crisis of the past few years has also been formative, in that it has reinforced my view that the near future is often far more discontinuous with the present than is commonly imagined.