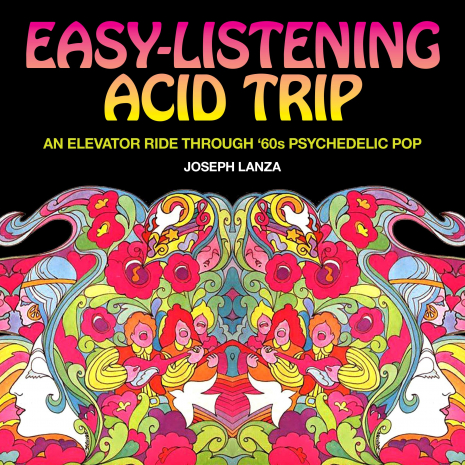

Author Joseph Lanza is an expert’s expert on some of the more enigmatic corners of popular and unpopular culture. In numerous books he’s written about Muzak®, long forgotten crooners, obsessive film directors like Ken Russell and Nicolas Roeg, bland pop songs, the history of cocktails, and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Possessing an expertise on matters from Mantovani to Leatherface, Lanza’s work is quirky and unique. His latest book, Easy Listening Acid Trip: An Elevator Ride through Sixties Psychedelic Pop (Feral House) covers a musical genre that most people have no idea even existed.

It’s bound to send prices skyrocketing on Discogs for this kind of stuff. Like all of his books, it’s a fun read.

I asked Joseph Lanza some questions over email.

In your books, you display an erudition about obscure popular culture, and you seem to have staked out a territory, where others have feared to tread. How did you become interested in, and an expert on, elevator music and pop orchestral cover versions of psychedelic hits?

I’ve been curious about this kind of music since my high-school days. While listening to the garden-variety rock and pop along with my peers, I was also fascinated by the easy-listening instrumental FM station that my parents often kept on in the background. They seemed to be broadcasting phantom orchestras and choruses that covered many current songs, and I remember being amazed to hear the Ray Conniff Singers do a version of Gordon Lightfoot’s “If You Could Read My Mind.” Though their vocals were engineered to be more background than foreground, the song seemed all the more haunting with its references to old-time movies and ghosts. Its subject matter was close to the ideas and images in Roger Corman’s 1967 movie The Trip, which helped to introduce LSD themes to the masses. The Conniff recording has a spectral appeal that, for me, brought out this message more than the original record.

In college, I would listen to recording artists like Nico by day, and at night, I’d turn on the local elevator-music station. It sounded like tunes from a parallel place, and I liked this. At the same time, I recall standing in a bank line, hearing similar music from the ceiling speakers, and seeing what looked like a thermostat dial on the wall; it was really a Muzak volume setting.

Can I assume that you mainly listen to this sort of music?

I’ve collected a lot of this music through the years and listen to it much of the time. But I also like sixties pop and folk rock by Donovan, The Searchers, and even the echo-drenched ballads produced by Joe Meek. Peer Raben’s music to the Fassbinder films is also appealing, and Raben had expressed Mantovani’s influence in some of his work.

What is it about this sort of fare that captured your attention?

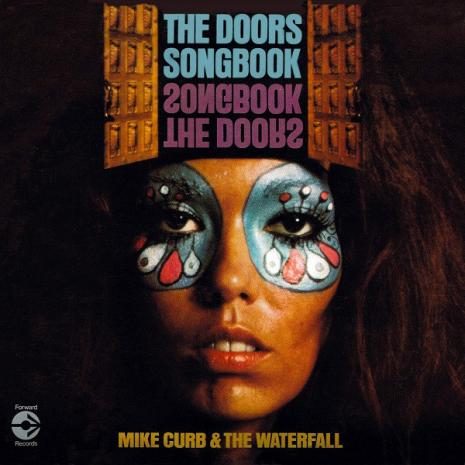

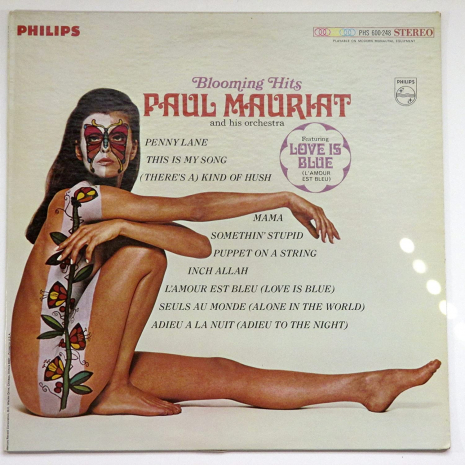

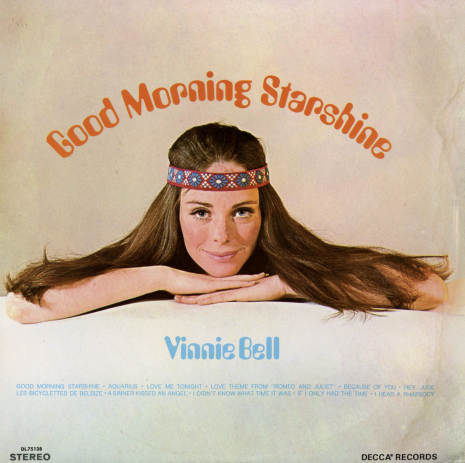

It played almost everywhere, in different places, and it attracted me more with the passing years. I wondered about the people and the studios that put these sessions together. This music was not the product of some indifferent machine but by reputable session players who also did backgrounds to some pop albums and Top 40 songs. Vinnie Bell is one example. He contributed to Muzak sessions but also played his “water guitar” on Ferrante & Teicher’s “Theme to Midnight Cowboy.” The term “elevator music” has accumulated pejorative connotations, but it’s ultimately a positive term. It’s music that, like an elevator, floats in the air, often between destinations: airports, hotel lobbies, and malls And it triggers sometimes-ambiguous emotions. In the late ‘40s, Muzak and the Otis Elevator Company ran an ad in Time magazine, showing happy elevator passengers, and touting how, thanks to “Music by Muzak,” “the cares of the business day are now wafted away on the notes of a lilting melody.” This gives the term an historical context. And in the late sixties, at the height of the “counterculture” and political violence, easy-listening tunes like Paul Mauriat’s “Love is Blue” played on the same Top 40 stations that also played the Doors and Jefferson Airplane. During my research for the book Elevator Music, Brad Miller, who’d engineered and produced the early Mystic Moods Orchestra albums, told me that they were also popular among Bay Area youth. He claimed, “the pop music at that time was trying to provide more texture as opposed to the usual electric rock bands.” The psychedelic appeal was not like a Jetsons-inspired vision of the future but a melancholic gaze into the past that often revived old sounds from the British music hall, American vaudeville, and Tin Pan Alley. This helps explain why easy-listening (with its emphasis on traditional melody) and psychedelia formed an uncanny merger. Even the Rolling Stones took the time to go back to their European roots with ditties like “She’s a Rainbow.”

Have you met many others who share your interest in this most specific of musical genres, or are you a bit of a lone wolf?

In 1984, when Muzak celebrated its 50th Anniversary, I contacted the company and got a folder full of information about its history. Later, as I started writing Elevator Music in the early ‘90s, I was meeting and talking with several programmers who had worked at Muzak. I also had extended conversations with some who had programmed for easy-listening instrumental channels, or the so-called “Beautiful Music” stations, which were among FM’s most popular formats. Then, going into the ‘80s, the format gradually ceded to “Adult Contemporary,” which replaced Percy Faith, Ferrante & Teicher, and the Hollyridge Strings with the likes of Neil Diamond, Frank Sinatra, and Barbra Streisand. We got blasted with “foreground music” and were eventually robbed of a musical background.

Today, I am far from being a “lone wolf” in liking this music. You can go to YouTube and type in “Muzak Stimulus Progression,” “easy-listening instrumental music,” or any particular recording artist like Paul Mauriat or Franck Pourcel, to find many fans leaving messages about how they like these recordings and miss their presence in public places or on the home hi-fi. Some reminisce about a long ago and far away time when such sounds permeated the malls, shopping plazas, and supermarkets during their childhoods.

Who do you find are the greatest practitioners of the easy-listening acid cover version genre?

My favorites are the Hollyridge Strings, especially their albums of songs by the Beatles during the Sgt. Pepper years. Their versions of “A Day in the Life” and “Strawberry Fields Forever” are heavenly, and they even had the gumption to play an echo-redolent, orchestral cover of “I am the Walrus.” Both David Rose and the Johnny Arthey Orchestra did great versions of Donovan’s “Wear Your Love Like Heaven.” As early as 1965, both Rose and James Last record released their interpretations of “Mr. Tambourine Man.”

Are there any particular numbers in the Spotify playlist you compiled that you wanted to comment on?

Spotify did not seem to have many of the tracks I wanted, but among the ones I did find, the 101 Strings’ version of “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear Flowers in Your Hair)” is a favorite because it got released not long after Scott McKenzie’s original 1967 hit. It reinforces that fascinating contrast between background and foreground. The Percy Faith Strings provide a mellifluous take on “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds.” A wild card in the bunch is the Shadows’ “Wonderful Land” from 1962. Its combination of spacey surf guitars with Norrie Paramor’s lush orchestra foreshadowed the easy-listening psychedelia that would emerge just three years later. The same applies to James Last’s version of “Telstar.” Into the ‘80s, the Wallis Blue Orchestra provided an intriguing tribute to David Bowie’s “Space Oddity.” Though many associate it with the early ‘70s glitter era, the song fits more in the last gasps of the psychedelic years because Bowie released it in 1969, around the time we landed on the moon. Major Tom is floating in space, but his mind is on returning to a home he’ll probably never see again. As an easy instrumental, even without the lyrics, the song’s mood seems even more wistful than on the original. That’s how I appreciate easy-listening psychedelia in general.