Mid-1970s Bowie is my favorite Bowie. 1975-1976, living in the Los Feliz house of Glenn Hughes, bassist for Deep Purple. Bowie’s coked out and coked up, obsessed with the occult and given to paranoid delusions. Bowie consorting with witches. Bowie starring in Nicolas Roeg’s excellent The Man Who Fell to Earth and releasing Station to Station, perhaps his most scorchingly funky album and also, as it happens, my favorite of Bowie’s albums. These were the “Thin White Duke” years, as the first line of that album has it; whatever was possessing Bowie, to quote the same song, “It’s not the side effects of the cocaine / I’m thinking that it must be love.”

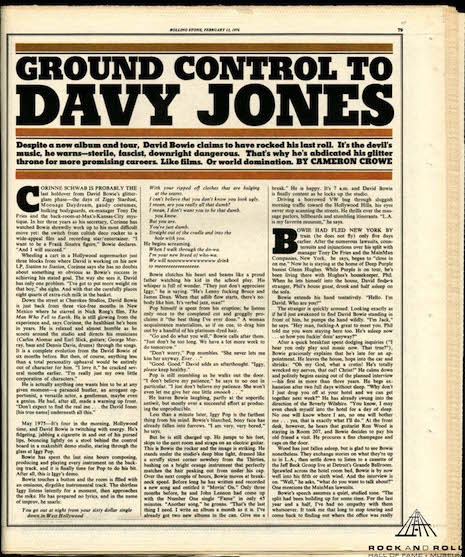

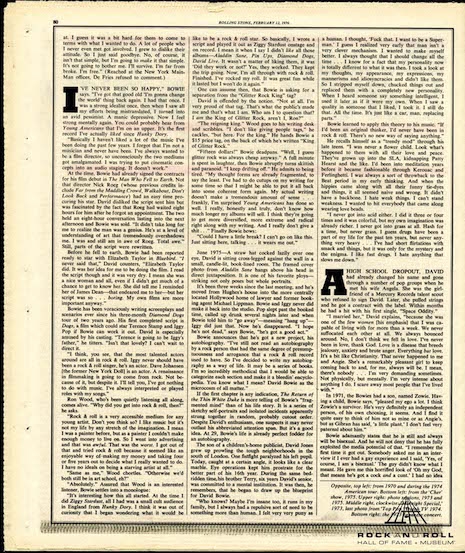

The primary chronicler of this period in Bowie’s life was unquestionably Cameron Crowe, whose youthful journalistic exploits for Rolling Stone were depicted, after a fashion, in Almost Famous. Not only did Crowe write a cover story on Bowie that appeared in the February 12, 1976 issue; he also interviewed Bowie for the September 1976 issue of Playboy, an interview that featured several remarkable statements, most prominently, that “yes, I believe very strongly in fascism.” Amazingly, Crowe was a teenager when all of this was happening—he turned 20 in July 1977.

If you are a David Bowie addict, it’s fairly likely you have read these lines, which appeared in Crowe’s 1976 feature on Bowie for Rolling Stone:

Bowie announces that he’s got a new project, his autobiography. “I’ve still not read an autobiography by a rock person that had the same degree of presumptuousness and arrogance that a rock & roll record used to have. So I’ve decided to write my autobiography as a way of life. It may be a series of books. I’m so incredibly methodical that I would be able to categorize each section and make it a bleedin’ encyclopedia. You know what I mean? David Bowie as the microcosm of all matter.”

If the first chapter is any indication, The Return of the Thin White Duke is more telling of Bowie’s “fragmented mind” than of his life story. It is a series of sketchy self-portraits and isolated incidents apparently strung together in random, probably cutout order. Despite David’s enthusiasm, one suspects it may never outlast his abbreviated attention span. But it’s a good idea. At 29, Bowie’s life is already perfect fodder for an autobiography.

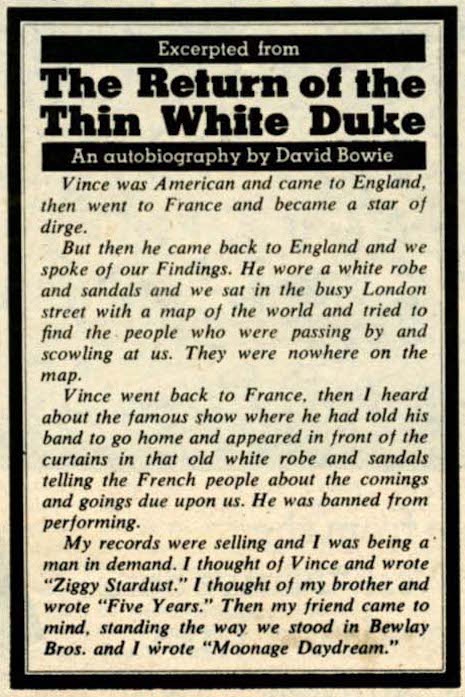

The article in Rolling Stone also included an excerpt, in a box. It looked like this:

So Bowie gave Crowe a manuscript of some sort. What was in it? Has it ever been published in full?

This “first chapter” of The Return of the Thin White Duke clearly has never been published. I consulted ten book-length treatments of Bowie’s life and career (a list of these works can be found at the bottom of this post), and only 2 of them even bothered to mention it, and neither dwelled on it for very long. It’s abundantly clear that not many people know anything about this text.

Bowie: A Biography by Marc Spitz includes the following on page x of the introduction:

Bowie’s autobiography, purportedly entitled The Return of the Thin White Duke (after the opening lyric to the 1976 song “Station to Station”) has been rumored for years as well, but either the asking price is too high or it’s a bluff; or it’s really in the works, and like Bob Dylan’s Chronicles volume one, it will arrive when it’s the right time.

Meanwhile, in The Man Who Sold the World, Peter Doggett writes on page 285:

Much of The Man Who Fell to Earth was filmed in Albuquerque—the so-called Duke City, having been named for the Spanish duke of Albuquerque, Spain. And it was there that David Bowie, who was unmistakably thin, and white, began to write a book of short stories titled The Return of the Thin White Duke. It was, he explained, “partly autobiographical, mostly fiction, with a deal of magic in it.” Simultaneously, he was telling Cameron Crowe: “I’ve decided to write my autobiography as a way of life. It may be a series of books.” Or it might be a song—or, as printed in Rolling Stone magazine at the time, the briefest and most compressed of autobiographical fragments, which suggested he would have struggled to extend the entire narrative of his life beyond a thousand words.

In 2012 the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame opened its Library and Archives in Cleveland, Ohio, and one of the institution’s most intriguing holdings is the Rolling Stone Collection, which contains the editorial files, notes, work product, etc. for all issues starting in 1974 and stretching all the way to 1989. It’s a lot of super-interesting material to which all rock journalists should be paying attention.

The manuscript of chapter 1 of The Return of the Thin White Duke that Bowie gave to Crowe is in those files, and I’ve read it in its entirety.

Rolling Stone’s arrangement with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Library and Archives does not permit visual reproduction of its work product, so it is not possible for Dangerous Minds to post the pages of this manuscript here. However, researchers are permitted to quote portions of items found in the Rolling Stone Collection—I was told that I am permitted to quote 10% of the manuscript as “fair use.” I’m going to do just that, in a minute.

When I first encountered this at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Library and Archives, I excused myself from the archive (cellphones are not permitted in the room itself) and Googled a few choice phrases to see whether anyone else had ever published it. I came up with zero hits in all instances.

The manuscript is nine pages long, typewritten. What’s contained in the archive is a Xerox copy of the original; where the original is, I have not the slightest idea. On the top of the first page is typed, in allcaps, “THE RETURN OF THE THIN WHITE DUKE.” Underneath that, in someone’s handwriting—perhaps the author’s, perhaps Crowe’s—are the words “BY DAVID BOWIE.”

It is quite a remarkable document, with Bowie inserting often mundane impressions of the past into a grandiloquent, over-the-top sci-fi allegorical construct reminiscent of Genesis’ The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway or, indeed, Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars. (Just to give you an idea, the named characters in the manuscript include the “Thin White Duke,” the “Finder,” the “Fatal Father,” and “Magnauseum.” I think.) As for the more workaday parts, there’s a paragraph comparing the relative merits of chisel toes versus high pointers (these are types of shoe), with Bowie, in whatever fictive guise, preferring the chisel toe. Another longish passage is dedicated to the decisions involved in painting his home: “Deep blue was the color that I took to every dwelling,” starts Bowie on that subject.

The text is broken up into many, many shorter sections, most of which are just a paragraph or two long. For some reason Hebrew letters are used to distinguish the sections (ALEPH, BETH, GIMEL, DALETH, HE, VAU, ZAIN). In between the more prosaic bits that are apparently about Bowie’s own life are sections in which the Thin White Duke and possibly others—it’s not quite clear—present their verbose and overblown pronouncements about life and music and fame.

Oh, also? There’s a fair bit of sex in it. A couple of the passages are quite steamy.

Overall, I think everything Crowe and Spitz and Doggett wrote is accurate, if a little dismissive. Doggett’s observation, that Bowie “would have struggled to extend the entire narrative of his life beyond a thousand words”—clearly Doggett has a point insofar as, after all, Bowie never did write his autobiography, and it is not easy to imagine anyone writing or reading 300 pages in Bowie’s chosen register. But—well, Bowie probably could have written another fifty pages of it without much difficulty.

For his part, Crowe, at the age of 18, may not quite have been capable of apprehending that perhaps Bowie’s words should be regarded as a draft. As a finished product, Crowe was perfectly right, the nine pages of The Return of the Thin White Duke are not ready for prime time—the main problem with the text is that it’s awfully confusing and disorienting, nothing is introduced properly, and it switches registers so rapidly that the reader is never on solid ground about much of anything.

However—as a draft, it’s pretty damn distinctive, and pretty damn promising. The writing is rather good—it gets pretty purple in parts—but it’s pretty clear what Bowie is after, and he achieves a tone I’ve seldom encountered, one that blends the homey and the flashy pretty effortlessly. It certainly seems an accurate representation of Bowie’s meticulous, grasping mind—and I don’t just mean Bowie’s paranoid/coked-up mind of 1975-76—and he’s perfectly eloquent and strikingly original in sections.

I think what an editor would have recommended is to cut down on the big grandiloquent speechifying—keep some of it, however—and expand the autobiographical or impressionistic sections. Even in this sketched, fractured state, there is a poignancy to it, which may partly derive from all the evident subterfuges that Bowie used to prevent it seeming so.

I’ve transcribed a few sections so that readers can get a taste of what this manuscript is like. In all cases the carriage returns are reproduced accurately in addition to the words. There are a few typos and a few curious spellings etc., please be assured that if you spot a typo, it exists in the original as well.

From page 3; the year is 1975, the present day:

BETH Worldwide Video Speech.

The Thin White Duke Continues.

“Here and now there is no asylum to wake for, for

you have been rocked. Soon you will be rolled by the

illusion of a dawn that has been dragged our from the

bowels of the vile entities of inhumanity. A false

dawn, stripped of its puce and turgid jism by the

Divine Witch Magnauseum, the smog drab Pretender who

crawls up from the sewers from the suffercation of the Witch’s

omnipotent embrace, to enter our hideous sub-domain,

stinking with eternal damnation. The gravestones

nervously agitate time while, upon them, greed lights

its candle to the possession of youth.”

I don’t think I’m betraying any trade secrets by revealing that “puce and turgid jism” was one of the phrases I used as a trial string to discover whether this text existed on the Internet.

From page 6, a sex scene:

ZAIN New York February 1975

Fucking Magnauseum

I’m rigid with sensation. I feel my tongue lapping

toward her womb. I move around and move around her and move

and I move around her writhing and her writhing form to snatch

and suck at and suck at the nape of her neck. The short curly

hair tasting of some special brew, searched for, prepared and

applied. I’m slow, hard, fast, solid then so slow and pulsat-

ing that I perceive the indifference of a time-warp. The

gossamer sweat seems to pale her blackness to an almost drab

yellow sheen.

From pages 7-8; the year given earlier is 1961, when Bowie himself was about 14:

HE CONTINUES

My grey flannel pants have been tapered at the cuffs to a

tight thirteen inches. Waiving aside the Perry Como, I chose

for class today the thin blue on white accountants stripe with

its starched white collar.I catch sight of myself in the living room mirror and

take pride in those buttocks. My cock looks bulgy and tough.

[page break]

Denis, all wreathed in smiles under his short curly hair,

tells me that if I just pinned the badge to my school blazer,

silk and wool, I can take the badge off when catching the bus

home.

From page 8; back to 1975, and the Duke is continuing his great speech:

Like monkeys free and berserk in the cockpit of

some great airship, havock grasps this newly wrenched

rib of God.And all of the imbeciles and cretins, who had been

delegated to some other imperceivable providence of their

own, have tumbled and fallen from the sky, soared spouting

from the seas. The catastrophic menage is ripping and

torturing their release from the soul of OM. And the

rock bands just dirge and provacate the malforms into the

frenzid waltz of [infinity symbol].

I wish I could reproduce more of this remarkable text, I really do.

DM has reached out to Cameron Crowe for a comment but he is busy on a TV shoot and was not able to provide any response to our queries. We would be delighted to run any statement he elects to furnish us, and the same goes for David Bowie.

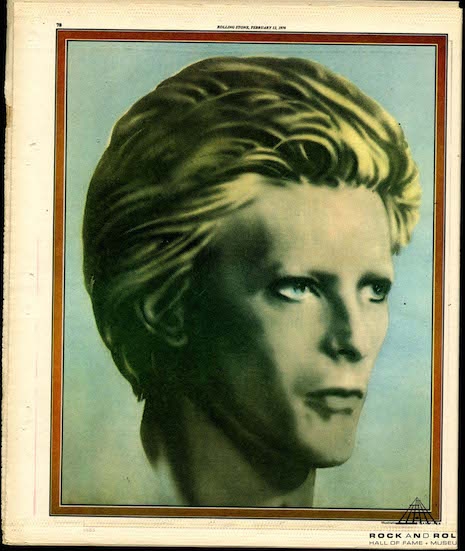

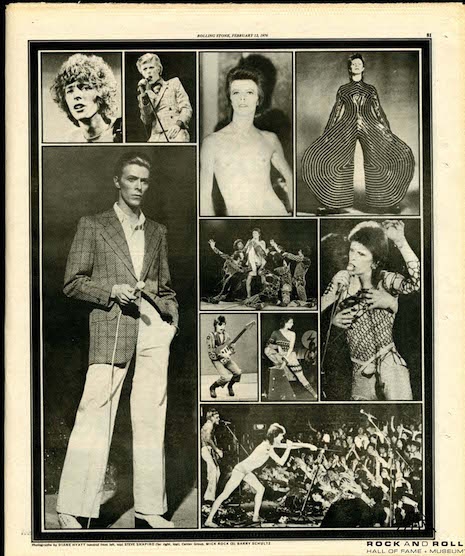

Here’s Crowe’s Rolling Stone article in full; the cover is above. Clicking on any of these images will yield a larger version of the image.

Here are the works I consulted in which The Return of the Thin White Duke is not mentioned, as far as I can tell:

Stardust: The David Bowie Story, by Henry Edwards and Tony Zanetta

David Bowie: Starman, by Paul Trynka

David Bowie, Album by Album, by Paolo Hewitt

Strange Fascination: Bowie: The Definitive Story, by David Buckley

Alias David Bowie, by Peter and Leni Gillman

Ziggyology, by Simon Goddard

David Bowie Is Inside

The Complete David Bowie, by Nicholas Pegg

I found all of this material at the Rock Hall’s Library and Archives, which is located at the Tommy LiPuma Center for Creative Arts on Cuyahoga Community College’s Metropolitan Campus in Cleveland, Ohio. It is free and open to the public. Visit their website for more information.

And just because, here’s David Bowie on 1975’s Grammy Awards, a revealingly “otherworldly” appearance that says at least “something” about his state of mind at the time, even if I’m not entirely sure what that might be.