Robert Mitchum hated being a movie star. Being famous meant nothing to him. After all, as he often pointed out, one of the biggest stars in the world was Rin Tin Tin, “and she was a four-legged bitch.” Acting wasn’t real work. Real life was always more important than any two-bit ham who turned up, hit his mark and said his lines on cue.

Mitchum once claimed he had only two types of acting, one type for when he was on a horse and another when he was off. There was always this sense he was somewhat embarrassed by all the adulation from fans and sycophantic journalists who thought they owned a piece of him. It made Mitchum hate Hollywood with “all the venom of someone who owed it everything he had.”

Yet for all his bravado, Robert Mitchum was one of Hollywood and cinema’s greatest actors. Over fifty-four years, Mitchum appeared in 110 movies. Many which were then and are still now considered among the best movies ever made—and this was often down to the quality of Mitchum’s performance whether he on or off a horse.

While he was happy to share stories about his life and career with family and friends, Big Bad Bob had a reputation of being difficult to interview. Chat show host Michael Parkinson once had a very awkward interview with Mitchum where every question asked by Parkinson was met by the sleepy-eyed actor’s answer “Yep.” After about twenty minutes, Parkinson had had enough of this monosyllabic performance and asked if Mitchum if he ever said anything other than “Yep”? To which Mitchum replied, “Nope.”

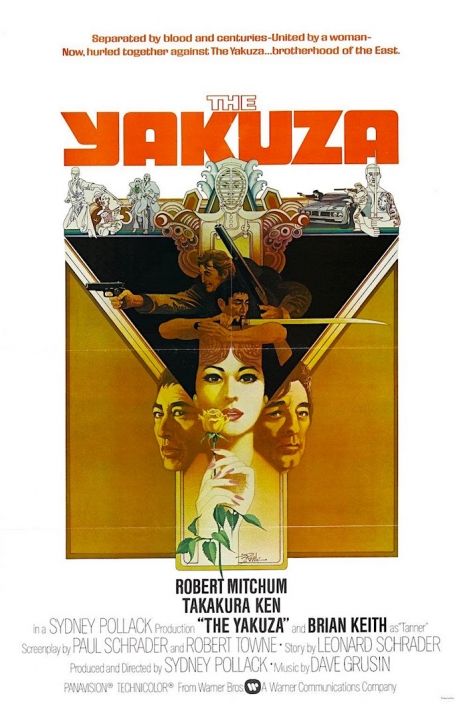

In January 1974, Mitchum arrived in Tokyo, Japan, to star in a gangster movie called The Yakuza. The script was written by two young writers, brothers Leonard and Paul Schrader. The film came about after Leonard Schrader went to Japan to dodge the draft in 1968. He found a job teaching, but when this fell apart, Schrader started to hang out with young yakuza gangsters. He was intrigued by their sharp suits, wraparound sunglasses and strict code of honor. He wanted to write a book about these gangsters but his brother Paul convinced him to turn it into a movie script instead.

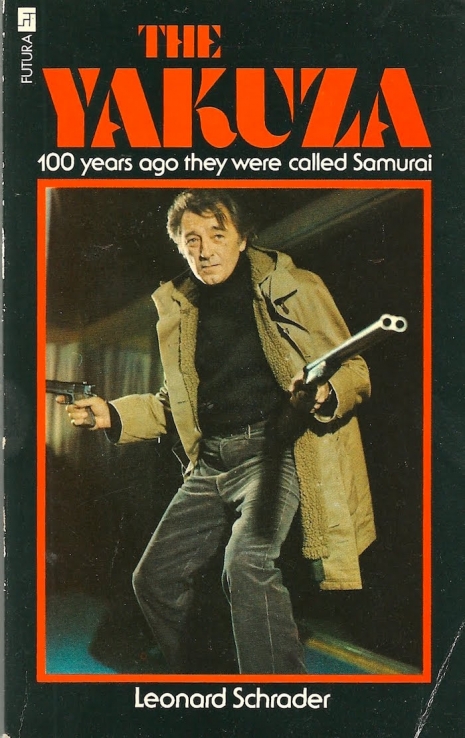

Leonard Schrader’s book ‘The Yakuza.’

Written over a few weeks The Yakuza tells the story of a retired detective Harry Kilmer (Mitchum) asked to rescue a friend’s daughter who has been kidnapped by a yakuza gangster, Tono (Eiji Okada). Kilmer worked as a military policeman in Japan after the Second World War where he formed a relationship with a local woman Eiko (Keiko Kishi) who was working the black market to obtain penicillin for her sick daughter. Eiko’s brother Ken (Ken Takakura) a recently returned Japanese soldier was outraged by his sister’s friendship with the enemy. Kilmer ended the relationship with Eiko after helping her find the drugs for her child. He then returns to Tokyo to enlist Eiko and Ken’s help in saving his friend’s daughter from the yakuza.

The script was hyped as “The Godfather meets Bruce Lee.” It started a bidding war among the studios which eventually delivered a $325,000 payout to the brothers and their agent—though Leonard only made twenty percent of the take. A young Martin Scorsese read the script but Paul Schrader wanted a big name to direct. Robert Aldrich was hired with Lee Marvin as lead. When Marvin dropped out, Mitchum took over. However, Mitchum stipulated he did not want Aldrich as director—there was bad blood between the two. Mitchum said he wanted Sydney Pollack instead.

Pollack may have seemed an odd choice. He had just finished making The Way We Were a slushy romantic feature with Barbra Streisand and Robert Redford. However, he had also directed the war movie Castle Keep, the western The Scalphunters, both starring Burt Lancaster, and the Oscar-nominated They Shoot Horses Don’t They? starring Jane Fonda and Michael Sarrazin.

Pollack liked the script but thought it needed a rewrite. He brought in Robert Towne, who had written Villa Rides for Sam Peckinpah, The Last Detail for Hal Ashby and was then working on Chinatown for Roman Polanski. Towne later explained his involvement with The Yakuza:

...in Japan, Yakuza films are sort of B-movies, where these gangsters … they’re sort of a combination of … if you took out soap operas on daily television and our B-gangster movies and mashed them together, you’d get a Yakuza film. Because the Japanese are very melodramatic, particularly in these films, in almost everything. And all these gangsters are stricken with this terrible sense of duty and obligation, that they’re obliged to do these things, so that in the end they end up killing 25,000 people or themselves or both or mutilating themselves. What was interesting to me was that the story deals with an American who goes over there to do a favor for an old friend. And in order to do this favor for an old friend, he has to see a Japanese gangster whose sister he had once been in love with, and asks him to help him rescue this friend’s daughter from other Japanese gangsters. And the kind of tangled web of obligation that results from this was interesting to me to work with, to make actions that are almost kind of … they’re really like a fairy tale. You just don’t imagine some guy getting to the point where he’ll be able to kill 25 people. To try and make that credible was interesting to me. And it deals with things like loyalty and friendship and abiding love, and it’s very romantic. And it was fascinating to me.

~snip!~

I took it to be my task in reworking it, in the structural changes I made and in the dialogue changes and the character changes, to make it, from my point of view once you accepted the premise, credible that this American would go over there, would do this, would get involved in the incidents that he got involved in the script which would involve recovering a kidnapped daughter and then ultimately killing his best friend and killing 25 other people along with it and immolating himself. And I thought that in my reading of it, I just didn’t feel that he was provoked in the right way to do all that. It’s hard to make it credible that somebody would do that, and I tried to make it, from my point of view and the point of view of the director, more plausible. Not absolutely plausible, but plausible in the framework of this kind of exotic setting. […] When I had read it, I said these are the things that I felt should be done, and they agreed with me, so I did them. But it was pretty much agreed upon with the director and myself.

Original theatrical trailer for ‘The Yakuza’ (1974).

When Mitchum arrived in Tokyo to start filming, there was a hastily arranged press conference at which he unleashed his couldn’t give a fuck side when he told the assembled journalists:

“Remember Pearl Harbor.”

Everywhere Mitchum went he was mobbed by fans who chanted:

“Please Kirk Douglas-san, your autograph!”

He developed a taste for sake and became friends with some real-life yakuza gangsters, as Mitchum’s biographer Lee Server recounts:

One man showed Mitchum his automatic pistol—it was ten years in prison if you were caught holding it. “If anyone gets in your way while you’re in Japan,” a thug calmly told him, “just let us know. We’ll cut him down.”

Mitchum was in his fifties—an age when most actors are thinking about slowing down, playing character roles or retiring to the sunny climes of Florida—but still making some of the seventies’ greatest movies. He had started the decade with Ryan’s Daughter, and had just completed The Friends of Eddie Coyle—which is easily one of the greatest crime movies of the 1970s or any decade. Period. Now he was upping the ante with this complex, multi-layered Japanese gangster movie.

Out of the screenplay by the Schraders and Towne and from Mitchum’s powerful, mesmerizing performance, Pollack crafted a superlative, intelligent movie. I first saw The Yakuza when I was a kid. It made a permanent mark on my imagination. And with each return viewing, I have often uncovered something previously unnoticed, or reinterpreted a line of dialog or a facial nuance in a different way. But at its heart the film tells the story of a relationship between three complex people and their differing moral codes—which is something Pollack stated in a short behind the scenes insert:

From my point of view, I always felt that this picture was basically about three people who refuse to accommodate to change to the changing morality of the time. They’re almost antiques in a sense. They remain true to a set of standards, ethics and morals that has existed for them all of their life. They have never bent with the fad of morality that changes constantly. And there is an enormous bond of love that exists between the three of them—between the two men and the woman and the two men. It always seemed to me in the simplest terms the movie was about promises kept. Robert Frost wrote a poem a long time ago that made a very vivid impression on me which was something I kept thinking about while I made this film which was:

The woods are lovely, dark and deep.

But I have promises to keep.

And miles to go before I sleep, miles to go before I sleep.And that phrase was always very evocative to me. This is a story about three people really who all had promises to keep and who keep them.

Check out the whole of this short clip where Pollack offers his insight into filmmaking and the meaning of The Yakuza.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

Beyond Good & Evil: Behind the scenes of ‘The Night of the Hunter’

Robert Mitchum gets busted for ‘reefers,’ making weed seem hip to middle America

Acting is ‘better than working’: Robert Mitchum interviewed for French TV

Yakuza: Beautiful hand-painted vintage portraits of tattooed Japanese gangsters