This is a guest post from Matthew O’Shannessy

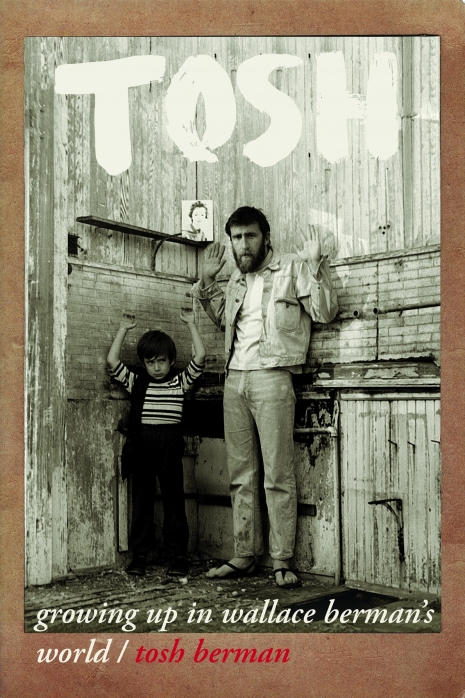

Tosh Berman’s memoir Tosh: Growing Up in Wallace Berman’s World documents a childhood immersed in West Coast bohemia, from the Beat era of the 1950s through to the crumbling ruins of hippie idealism in the 1970s. Through his father, the cult artist Wallace Berman (who was tragically killed in a car accident in 1976), Tosh gained first-hand experience with an eclectic cross section of post-war culture growing up amongst many now-iconic poets, artists, actors, musicians, and counter-cultural figures.

Despite Wallace Berman’s celebrated connections (his face appears on the cover of the Sgt. Pepper’s LP), the artist has remained an enigmatic figure, little known outside the art world where he is venerated for his Verifax collages and assemblages that combine popular culture, Jewish mysticism, and pornography. His handmade journal, Semina, featured writing by Alexander Trocchi, Michael McClure, Allen Ginsberg, and Jean Cocteau, and was purposely circulated mostly amongst friends.

Tosh presents an intimate view of the hermetic artist-father told as a non-linear coming-of-age story that stretches from the relative isolation of Topanga Canyon in Los Angeles to the bustling Beat scene of San Francisco’s North Beach. Everyday brushes with fame—drop ins by Brian Jones, a chance encounter with William Burroughs in the back of a London cab, getting caught up with notorious occultist Marjorie Cameron—are juxtaposed with the more mundane financial and logistical dramas of growing up with a father who rejected the straight world and all its trappings.

I spoke with Tosh at his home in Silver Lake, Los Angeles.

_465_249_int.jpg)

Matthew O’Shannessy: In the book, you mention that the TV Western “The Rifleman” was a reference point for your relationship with Wallace. Can you talk a little about that?

Tosh Berman: I always loved “The Rifleman” and during the repeats I would watch it over and over again. The story’s about a ranch widower and it’s just him and his son on the ranch. His son would have to help him out and they would go into town together. Like with me… you know, they can’t just go around the corner. He had to get on the horse and go into town and get everything. You know, eat dinner, have lunch, because it was too far to the ranch and back. Which is kind of like Topanga, away from civilization. So I started to identify with it, not only because of the relationship with my father but also the geography and the physical hardship of [living in a more] rural area.

I was with my dad consistently for my first 20 or 21 years. Except when I went to school or I visited friends, I never traveled alone. So I was always with my father. He was home all the time. I would hang out in the studio and help him make work. My mom was the one who did the actual work in the fifties and sixties. She’s the one who went out and made a salary. She’s the one who worked. My dad supported us when he sold art, which wasn’t that often, but he also made money by playing cards. He played with his friends and I remember once he played a game with Robert Blake who was a known actor that time. My mother hated him. She made him leave the house. She made my father take him somewhere else.

Topanga was very secluded at that time. It’s a canyon area of course, and people went to canyon areas at that time to get away from society, so not only did you get creative people and rich rock ‘n’ roll people, you also got the losers of all sorts, people who just can’t deal with the outside world or they’re paranoid. In the sixties, there was a lot of paranoia. Topanga became like a fort or fortress in this corruption of the sixties. It was totally a utopian thing. But I didn’t see as a utopian thing. It’s always been, to me, a depressing area. Very beautiful, but living there can be so difficult.

_Berman_465_259_int.jpg)

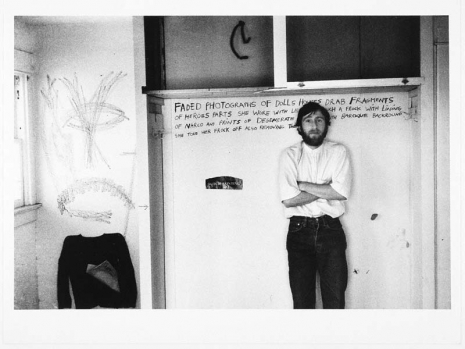

A portrait of Tosh Berman taken by his father. The woman in the photograph is Berman’s wife, Shirley.

One of the stories in the book that’s interesting to me is when Wallace takes you to the T.A.M.I. show. It’s the dress rehearsal and he has a film camera but he doesn’t film anything. Then later he watches the documentary of the concert and films the images of the bands off the screen. Do you think that says something about his artistic sensibility?

He never talked about his artwork or his techniques or why he did stuff. Never, to anyone. Around 64, 63, 65, he would carry an eight millimeter camera with him all the time—one that you had to wind up. At the time you could take it anywhere, there were no copyright issues or security issues.

My dad had it with him at the dress rehearsal and there were people like the Beach Boys sound checking, rehearsing. And I remember them well. They were totally in uniform. They had striped shirts, white pants, and then the Supremes came on afterwards and they all were in hair curlers and bathrobes. The only people in the audience that were our friends were like Toni Basil and the members of the Rolling Stones. That’s where we first met Brian Jones and I met Mick Jagger that night. My dad did not shoot anything. It wasn’t until the movie came out, because this was a film concept that played in theatres, that he actually shot footage of James Brown and shot footage of Mick Jagger.

I think my father’s aesthetic is that he needed to be distant, he needed another process between him and subject… rather than be directly in front of that person. He liked that idea of shooting off a movie or shooting off another photograph.

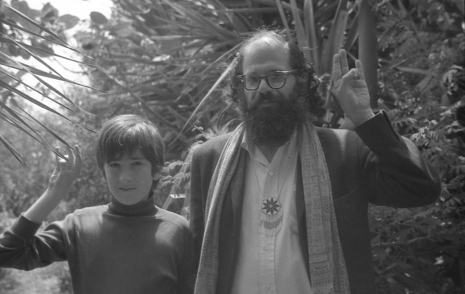

Tosh Berman with Allen Ginsberg.

You talk about how meeting Brian Jones had a big impact on you because you were a fan.

I met him when I was 10 or 11 years old and the last time I saw him was probably when I was 15 or 16, a teenager. I was a Rolling Stones fan. My father brought in rock ‘n’ roll records himself, but with allowance money I bought records as well. As he bought Rolling Stones records, I bought Rolling Stones singles. So, anyway, I was very aware of who Brian Jones was and his presence. When he came to our house in Beverly Glen, it was like he walked right off the Aftermath album cover, especially the back cover, always wearing a black turtleneck, white jeans, desert boots, like the classic Brian Jones look.

You say in the book that the first time you were really aware of fame is when you met Marcel Duchamp.

[Marcel Duchamp] was the first person I met where I went into to a room and I knew there was somebody important in that room. And everybody was focused on the importance of this one person, like a legendary iconic figure. And I knew he was an iconic figure and I knew this artwork actually because my dad always had a picture of his artwork on the wall in the studio. And I think mostly what I remember is the bicycle wheel. That appealed to me because the bicycle wheel, for a child, represents a bicycle. It’s very simple and very direct.

A lot of the chapters are named after significant people in your life, and a lot of them are now iconic. Was it strange writing about your own life that’s filled with encounters with people who have gone on to be mythologized?

That wasn’t strange to me. I realized that they were mythologized and iconic and when I was writing the book I didn’t feel that way because when I knew them, I knew them as a child. If I knew them when I was a grown up, I think it would be more like, “this is Dennis Hopper, the iconic actor”, but I was introduced to Dennis at a very young age, of course, and at the time it was before Easy Rider, so it was before “the iconic Dennis Hopper”. It was sort of “the local arts scene Dennis Hopper”. So while writing the book I didn’t really pick out iconic people. I didn’t try to think of people who would sell the book later or to make a blurb about it. I really sat down and wrote everything I can remember and it was just one long rambling manuscript. And then it was the suggestion of people who had read the manuscript to make it into smaller chapters. I started doing a chapter on Toni Basil or Dean Stockwell… Dennis Hopper.

As I wrote it I really wanted it to be multifaceted. I wanted the book to appeal to people who were interested in the arts aspect, the Beat Generation, Beat Era, as well as the coming-of-age / teenager-to-adult story as well. So from the beginning, I was aware that it was important to have these multi-levels coming through the book and hopefully one interest will expose the reader to another, maybe new interest.

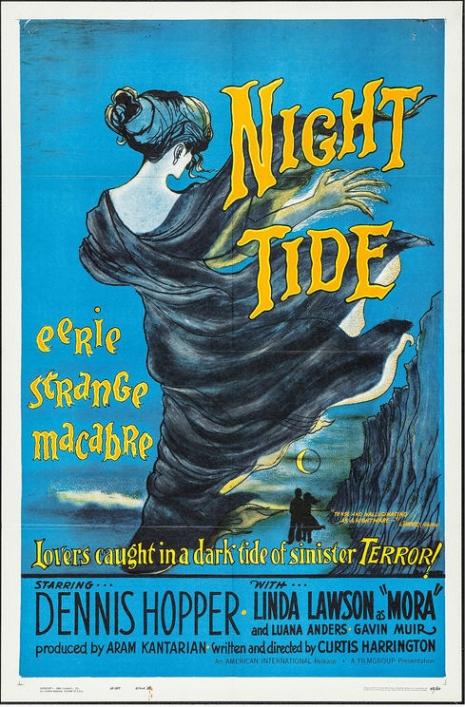

The extremely rare ‘Night Tide’ poster, via Westgate Gallery

In terms of the Beat Generation, you talk about the film Night Tide and how the bar scene is one of the more accurate representations of what the Beat scene was actually like…

For me that film is very accurate of that era. Curtis Harrington made the movie, who’s a friend of Kenneth Anger and was in a Kenneth Anger movie. An interesting filmmaker and all of that. And that’s an interesting movie because Dennis is in it and Dennis was a friend of my dad at that time. We sort of knew Curtis Harrington, I think we weren’t close friends but you know, being in the same city he and my dad were aware of each other. And of course, the one common person that everybody knew was Cameron. Cameron was the glue, the star, the bridge between all these people.

Cameron is a connection to a long history of a certain weird counterculture and LA, and like you said, she’s a connection to Kenneth Anger, and Aleister Crowley, L. Ron Hubbard, Jack Parsons, all these people. What was your relationship to her?

We were very close. She was like my mom and dad’s best friend. They met Cameron at Jack Parsons’ house when she was married to Parsons and what my mother told me was that they were invited to an afternoon party. Parsons had a lot of parties. It was mostly all rocket scientists, like nerdy guys. Cameron was there and she’s totally a bohemian person, not really a part of the rocket science crowd. I guess her interest in the occult is what got her and Jack together of course, and then the relationship bloomed beyond that.

So my dad showed up with a friend of theirs named John Brothers, I think that’s his name, who was a friend of Parsons and Cameron. Cameron saw my dad and mom and they weren’t like everybody else at the party, so she was immediately attracted to them. Eventually they did stuff together, like they would go to gallery openings or shows or see movies together and they all hung out together. Cameron and Parsons had a separate social life at times, and this is nothing negative about their relationship… Parsons had an interest in the arts, but not as much as Cameron did, so if Cameron’s going to go to a gallery somewhere, she will, and Parsons probably not.

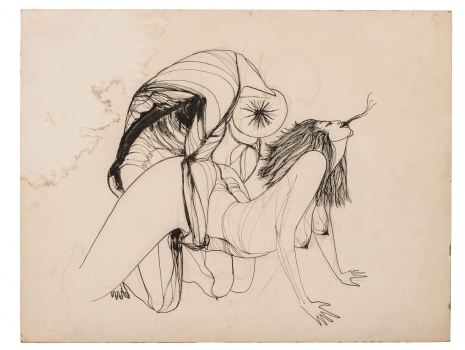

Cameron in Kenneth Anger’s ‘Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome.’

And you would see her around Topanga and places like that?

A lot. When I was a baby, what happened was, Parsons had his tragic accident. Tragic, you know, blew himself up and everything started happening at that point. It’s a weird incident. Weird death, and Cameron was totally beyond herself. She just totally lost it, I think. My parents were taking care of her. She was staying at our house in Beverly Glen.

At the same time, the first gallery thing happened with my dad [getting arrested]. At Ferus Gallery. And there are different theories about what happened. It’s been kept vague, not on purpose, but I suspect—I have no proof of this—Ed Kienholz, the artist and Walter Hopps the curator who owned the Ferus Gallery, they curated most of the shows, and I think Kienholz may have called the police, probably in the hopes of getting publicity for the show.

There was one piece [of my dad’s] that was definitely offensive, with a penis going into a vagina. Obviously this is the thing you’re going to get busted for in 1952, but the undercover cops or the vice squad that came, and whether they were bored or their jobs aren’t that serious, I don’t know, but they saw this drawing of Cameron’s from [my dad’s zine] Semina.

Untitled (Peyote Vision), 1955, Cameron (from Semina #1)

My dad had a piece that was a work of sculpture that he handmade, but he also included issues of Semina including individual pages and one of them was the Cameron drawing. No one in their right mind nowadays would consider it offensive. It was sexy, perhaps, but in no way obscene. Impossible… impossible! So the police saw Cameron’s drawing. They said, That’s it. We’ve got our evidence, now we can go get our donuts. So they arrested my father. They closed the show and it’s technically my dad’s work…but it’s actually Cameron’s drawing that got him arrested.

At that time, Cameron did not want to deal with any of those issues at all. There was a scandal in the press. That’s when it came out that she was a witch. And she didn’t want to get involved in that media thing and her nature was, I don’t deal with the courts, I don’t deal with cops…

My father was found guilty and I think the penalty at that time was like two days, or a fine and a day or two in jail or something like that. And I think Dean Stockwell, who’s a good friend of ours, especially at that time or all through my father’s life, I think he paid the bail for my father to get out of jail. At the time, there was no support from the galleries or the media… nobody.

Wallace Berman in an abandoned building on the Speedway in Venice, California, ca. 1955–57. Photo by Charles Brittin

You were surrounded by visual artists growing up. You were in a Warhol film and were cast in a Dennis Hopper film. What made you gravitate specifically toward writing and publishing [under your imprint TamTam Books]?

Since school I loved show-and-tell. I like taking something from home or from some place and showing it to my fellow classmates. It’s something of a taste issue. I have a certain taste and I want to share this with you because I really like it. It could be a book, a record, an object… that feeling never left me. So when I started publishing, it’s really another version of show-and-tell. This is what I’m interested in, so therefore I want to present this to you and show it to you. Same with the writing.

This memoir is very much a show-and-tell, one because I want to show the world how I see it, and also to share about my dad—he’s not super famous but he’s well-known within the art world and people who know about art, but he’s not like the Beatles…. he’s maybe Alex Chilton of Big Star. And there is stuff about my dad out there… there are books about him, or in books about Los Angeles or American art, but all of them are written by historians or critics, and after the fact. I wanted to tell these tales from my perspective, which is more personal.

Tosh talks Berman.