Jonathan Moore didn’t find starring in his latest film 2Graves an enjoyable experience.

“There’s a lot of it where I’m hung from a chain,” Moore tells Dangerous Minds. “A hook, like a meat hook. This went on for like twelve hours on the first day because we were so short of time. I stayed in my harness even during lunch break. I wore one these flying harness things. It’s like the worst kind of corset you can imagine—it digs into your ribs, it chafes—so, I was in a lot of physical pain. But I was using it—I was using the pain.

“The bloke who did the flying said to me, ‘We don’t normally have people in one of these harnesses for more than 20-minutes.’

“He said, ‘Are you all right? You don’t have to do this.’ I just felt so much pressure to do it that I did it for a whole day. I thought, well at least that’s done. Then I came in the next day and the director said, ‘You’ve got to do it again.”

Jonathan Moore is an actor, writer and director. He may describe himself as “not a marquee name,” but over a 30-year career, he has proven himself, time-and-again, to be one of the most powerful, original, and talented creative artists of his generation.

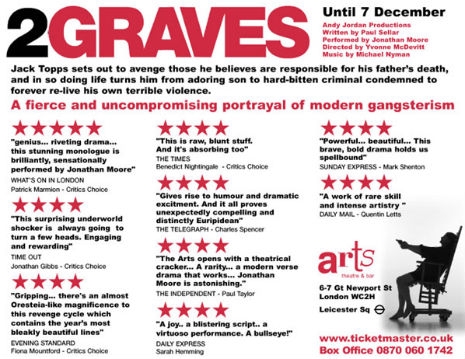

In 2Graves Moore plays Jack Topps, a man set on revenging the murder of his father.

“It’s got this kind of Greek revenge quality to it. It’s an odyssey really, about this guy who is an ordinary kid, whose dad is killed by gangsters over some gambling debts. His dad was a professional darts player and he didn’t throw the match to keep the local crime family happy. So, they killed him. His son finds out about this and he decides he’s going to embark on this spree of quite bloody revenge. It destroys his soul.

“The title comes from Confucius, ‘The man who achieves revenge, let him first dig two graves—one for himself.’”

Based on the stage play, 2Graves was written by Paul Sellar—“a fantastic writer,” says Moore, and directed by Yvonne Mc Devitt. The film maintains the scripts original trochaic tetrameter (DUM, da, DUM, da, DUM, da, DUM. da,) which give the movie its “hypnotic momentum.”

“It’s more like Performance, the Donald Cammell, Nic Roeg film, it’s more that,” says Moore. “It’s a psycho-gangster, it’s kind of trippy gangster, it’s not Guy Ritchie. And yet, it’s got an element of that sort of roghtie-toughtie, populist. it’s High Art meets Ronnie Kray.”

The film is tipped for cult success, which is some reward for Moore who found performing Topp’s descent into Hell, on stage and screen, a dark and painful experience.

“It was a kind of excruciating experience on stage, but especially with the filming of it was very painful and a lonely place to go to. I mean all that kind of dark stuff—I’m not particularly a Method actor, but I do believe in telling the truth, I do believe in be truthful in it, if you’re accessing that kind of dark areas. It was a very dark and lonely place to go to. I’m really glad it’s on film, but I’m very glad it’s in the past.

“I’m proud of it, I’m really proud of it. I think it’s a wonderful movie.”

It was as Thomas Chatterton, the doomed, pre-Romantic poet that I first saw Moore perform. This was during the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, 1981, in a play called I Die For None of Them. A one-man show that explained the events leading-up to Chatterton’s suicide in 1770. From the moment Moore appeared, he commanded the stage. He was a young firebrand actor, burning with an intensity and passion, that would later see him described as the “Johnny Rotten of the theater.”

“I remember when I first started on the Edinburgh Fringe with those shows, with my Punk theater company, and saying things like, ‘Anybody on the official Festival should be lined-up against a wall and shot.’ Really ridiculous. Then four years later, there I was on the official Festival with Greek!

“Then you start thinking, ‘Well, okay, anyone who gets an award should be put in a chain gang.’ Then there you are saying, ‘I’d like to accept this award on behalf of…’”

The following year, he returned with his play Treatment, the tale of priest confronted by a skinhead, which transfered to London, where it was described as “one of the most disturbing and exhilarating plays.” It was later filmed for television with Moore and Gabriel Byrne, and the two have remained friends since. Byrne has described Moore as:

“.... an artist of the highest rank.

“He has remained true to his calling, has not taken the easy road, but has spent most of his career experimenting, challenging conventional forms and visions.

“As well as being a profound writer and director, his exceptional moral character and his great gifts as a teacher and communicator are constantly in evidence. His rare gifts and talents enrich us all.”

It is probably their Catholic background that sees both Byrne and Moore consider their life’s work as a “vocation.”

“When we were kids, the idea of a vocation used to be kicked around quite a bit cause you know, ‘He’ll be taken for the Priests.’ For, you know, any of the lads that showed themselves to be a bit smart, or anything like that. That was always the word ‘vocation’ was used in application in vocation to the priesthood, and that was almost like being picked to play for your country.

“But actually, I think vocation can be a lot of things you realize that as you get older, and I think you got to be kind of a bit bonkers really to carry on as an actor, writer or director, whatever, which is what I have been doing for 30-years.”

Vocation for Moore is having to do what he has to do. It is something that compels him to dedicate his life as an artist to fulfilling his own creative vision, whilst producing an incredible body of work.

Moore was soon establishing himself as a writer and successful character actor. He could be found popping up in Midsomer Murders, or Jack the Ripper, as appearing in Bleak House or performing Shakespeare.

He also started to direct opera.

“It came about actually, by (God rest his soul) Steve Martland, who was looking for someone who wasn’t an uptight, opera-type to work with. Someone recommended me. Then Hans Werner Henze got wind of me, and asked if I’d direct Greek by Mark Anthony Turnage. We had a fantastic day together, hung-out together, drinking too much and having a good laugh. At the end of it, he said, ‘Would you meet this young composer to direct an opera?’ I said, ‘No. To be honest, it’s just not my bag. I don’t like the sound of it, I don’t like it really. I just don’t want to do opera.’

“And he said, ‘Why?’ I said, ‘Because it’s boring, it’s elitist, it’s got nothing to do with people that I know and care about. It’s just a sound, you know, that kind of screechy soprano vibe.’ I was just very honest with him. He said, ‘I agree with everything you’ve just said, that’s why people like you should be directing opera.’”

Moore co-wrote the libretto and directed Greek, an adaptation of Steven Berkoff’s original play, at the Munich Biennale.

“There’s an awful lot of talk about elitism, and this is a strange word ‘elitism.’ I’m certainly not for dumbing things down, in order to make them accessible. Because some things are a bit complex, and you do have to bloody work at it.

“It’s the difference between a really beautifully, well-cooked, lovely, organic, home-made food, and a Big Mac. They’re both food, but one takes a bit more effort. So, I have no problems with that. It’s the class aspect that I have issues with.”

In 1996, Moore directed James McMillan’s opera Inês de Castro at the Edinburgh Festival for Scottish Opera.

“I had guys on the crew at Scottish Opera, saying ‘I loved that show, I’ve been working here for 20-years, but I actually got my old man in to see that show and we all loved it.’

“That really meant a lot to me. More than any kind of rave review in the Guardian, or whatever. Call me old-fashioned, but I want people, like my uncles and stuff, to like my work, and to get something out of it. I’ve always felt that the challenge is to get complex stuff and make it accessible.

“Arthur Miller said he wanted his work to understood by a philosophy professor and a cab driver. That’s where I’m at with that sort of stuff as well. You go to Germany and certain parts of this country as well, and the more incomprehensible it is, the more profound it must be. Because clearly these people watching it are so convinced of their intellectual superiority and erudition, that they say ‘If they can’t get it, then it must be profound.’

“I think the real challenge is to make complex ideas gettable. To make the complex clear.”

Moore’s ability to make complex ideas accessible led him to work with Police founder Stewat Copeland, and Michael Nyman, who composed the music for 2Graves.

“I brought Michael Nyman along to the table, because I directed Michael’s first full-length opera, called Facing Goya, about the mapping of the Human Genome. That old chestnut for operas. Genome meets genome. It was beautiful. Michael and I got on really well, he’s a real mensch Michael, I like him a lot, he’s a real laugh as well.

“I’m a huge admirer of Michael’s,” continues Moore, “and [in 2Graves] it feels like Michael is the co-star of the film for me. I think his music is pretty much, I think, it’s me in every frame, but Michael’s music is there as well. The music has an almost operatic quality. The music isn’t incidental, it’s very much a part of what the film is, and I think that’s great.

“Michael’s music tends to lift everything to a special level. I just can’t imagine [Peter] Greenaway’s films, those early ones, without Michael’s music. Michael’s music lends those films a humanity.”

While Moore may not have received the wealth and great success his talent deserves, he is undoubtedly a genuine maverick of rare and brilliant talent that should be cherished.

“It is a struggle every day, as Peter Brooks said in that wonderful book The Empty Space, you have to question it daily. It’s like picking up your cross every day and getting on with it.”

The world premiere of 2Graves takes place tonight at the East End Festival. London.