Opening Scene:

Curtain up on a starry night. Comets fire across the sky. Center stage, one star shines more brightly than the rest, its spotlight points towards a globe of the earth as it spins from a thread. Glitter falls, as a white screen rises, the lights glow brighter filling the stage.

Blackout.

Single spot tight on a woman’s face

We are unsure if she is in pain or ecstasy. No movement until, at last, she exhales, then pants quickly, rhythmically. Her face glistens. The spot widens, revealing two nurses, dressed in starched whites, symmetrically dabbing her face.

The woman is Mrs. Kemp, and she is about to give birth. Three mid-wives are guided by house lights through the audience to her bedside. Each carries a different gift: towels, a basin of hot water, and swaddling.

It’s May 3rd 1938, and Lindsay Kemp is about to be born.

Blackout.

Though this maybe a fiction, it is all too believable, for nothing is unbelievable when it comes to Lindsay Kemp.

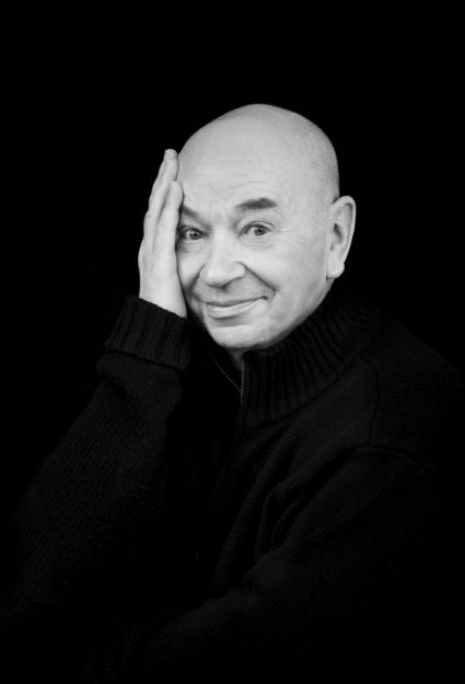

Lindsay Kemp has agreed to give a telephone interview. He is to be called at his home in Italy, by Paul Gallagher from Dangerous Minds, who is based in Scotland. We never hear the interviewer’s questions, only Kemp’s answers and see his facial expressions as he listens to questions.

Photographs of Kemp’s career appear on screens. We hear a recording of his voice.

Lindsay Kemp:

I began dancing the same as everybody does, at birth. The only difference was, unlike many other people, I never stopped. In other words, you know, I love movement. Movement gave me such a great pleasure, such a great joy.

Dance is really my life. I’ve always said for me ‘Dance is Life, Dance is Living, Dance is Life and Life is Dance’. I’ve never really differentiated between the two of them. It’s always been a way of life, a kind of celebration of living.

Kemp is an exquisite dancer, a fantastic artist, and a brilliant visual poet. No hyperbole can truly capture the scale of his talents.

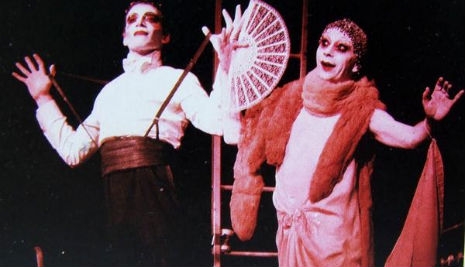

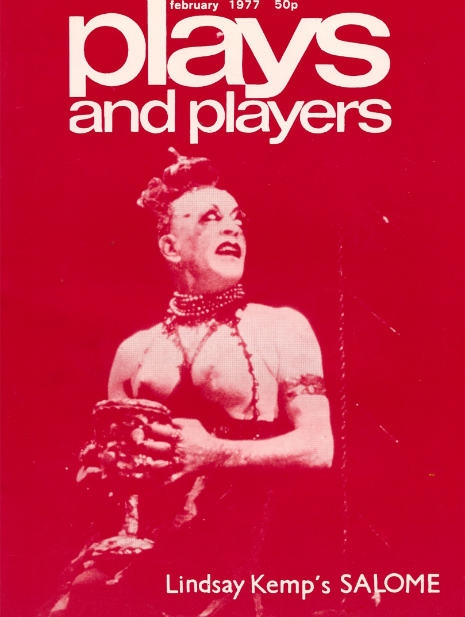

In the 1960s and 1970s, his dance group revolutionized theater with its productions of Jean Genet’s The Maids, Flowers and Oscar Wilde’s Salome.

He shocked critics by working with non-dancers. At the Traverse Theater in Edinburgh, he often cast his productions by picking-up good-looking, young men he had spotted in the city’s Princes Street Gardens - good looks, an open mind and passion for life were more important than learned techniques, or a classical training. His most famous collaborator was the blind dancer, Jack Birkett, aka The Great Orlando – perhaps now best known for his role as Borgia Ginz in Derek Jarman’s Jubilee.

Kemp was the catalyst who inspired David Bowie towards cabaret and Ziggy Stardust. He taught him mime, and directed and performed in Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, and was his lover. He also taught Kate Bush, and choreographed for her shows.

As an actor, he gave outrageous and scene-stealing performances in Jarman’s Sebastiane, Ken Russell’s Savage Messiah and Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man.

“I’ve never really differentiated between dance and mime and acting and singing. I’ve always loved all aspects of performing, though I still can’t play the trumpet, but I’d like too. Well, it’s never too late to learn.”

He has performed across the world, from department stores in Bradford, through the Edinburgh Festival, the streets and cafes of Italy, to London’s West End and Broadway.

Kemp is a poetic story-teller, and his performances engage and seduce as much as the words that spill from tell such incredible tales. His voice moves from Dame Edith Evans (“A handbag!”) to a lover sharing intimacies under the covers.

A house in Livorno. A desk with a telephone. A chaise longue. A deck chair and assorted items close at hand. Posters and photographs of Kemp in various productions are back-projected onto gauze screens.

Kemp makes his entrance via a trap door.

The phone rings once. Kemp looks at it.

Rings twice. Kemp considers it.

Rings three times. He answers it.

Lindsay Kemp is on the ‘phone.

Lindsay Kemp:

Hello. (Pause.) Where are you in Scotland?

(Longer Pause.)

My grandparents are from Glasgow. I always pretend to be Scottish because I was born accidentally in Liverpool when my Mother was saying bye-bye to my Father, who was a sailor, and he was off to sea from Liverpool’s port, you see.

(Longer Pause.)

Well, I don’t quite know where that came from, unless I said it one drunken night, maybe when I chose to be more romantic than Birkenhead, where I was in fact born. I was born in Birkenhead on May the 3rd, 1938, but my family hailed form Scotland, between Glasgow and Edinburgh, and for many years I lived in Edinburgh, when I returned there for the first performance of Flowers, that show that put me on the map, you know.

I did so many of my productions, including the first version of Flowers and Salome, and Genet’s The Maids . I did many, many things in Edinburgh, I only left when I was doing a production of The Maids, incidentally with Tim Curry, this was just before Ziggy Stardust, late ’71. And that production we were doing at the Close, was scheduled to open at the Bush Theater, and at the very last, we were all there rehearsing, ready to go on, and we got a call from Jean Genet’s agent, who said.

Spotlight on Jean Genet’s Agent, stage right

Jean Genet’s Agent:

No, no. Non.

Light out.

Lindsay Kemp

And we were refused permission to do the London version.

(Kemp examines some photographs on his desk, they appear projected on the screens behind him.)

Lindsay Kemp

I’ve got some pictures here of David Bowie at that performance, we gave just one performance, you see, which was a silver collection, we sold tickets for a collection. I don’t think David put anything in the hat. (Laughs.) Probably not, and I have some pictures here of David with his video camera, and he videoed that show, he videoed it, and sent his scouts out himself to find Genet, who he hoped might give us his permission. I’ve no idea what happened to the video, or if Genet got it, anyway, that was the end of that.

I played in The Maids myself at the Traverse for quite some time, playing Madame. But going back to Flowers, I’ll tell you how I began dancing in a minute, because we weren’t permitted to do The Maids that evening, we did Flowers instead, which was a production I’d recently done at the Traverse. So that production came to the Bush Theater, and it was there that it was seen by Larry Parnes, the pop music promoter, and he kind of restored an old cinema, which became the Regent’s Theater in Upper Regent’s Street, where Flowers began its West End run. From there it went to Broadway, and from there, you know, it went around the world.

I was…eh…I’d just rented a little cottage, a country retreat, in Hungerford in Berkshire, and my next door neighbor - it was one Sunday morning and we were listening to Round the Horne, we all did on those Sunday mornings - and my neighbor across the fence leaned over and said.

(Neighbor leans over a garden fence, Kemp is now sitting in a deckchair, still on the ‘phone.)

Spotlight up on Neighbor.

Neighbor:

Oh hi, I think this book might interest you.

(Neighbor passes Kemp a book. Spotlight down on Neighbor.)

Lindsay Kemp:

Holding up book.

And it was Genet’s Our Lady of the Flowers. And I began to read it, and as soon as I began to read it I could already see it on the stage, and I could see myself as Divine, the central character. And two weeks later, we opened.

Dim lights, then back up to reveal gauze removed and a young Lindsay Kemp performing ‘Flowers’.

Lindsay Kemp

As the performance continues behind him.

I remember so vividly. I went back up to Edinburgh, and an aunt of mine had left me five hundred pounds and with that money, we put the show on. I collected the actors in those days from Princes Street Gardens, young guys who looked right. And we did this first, semi-improvised performance, not at the Traverse, but in the old Edinburgh Rock Factory, under the Castle, on very much the Fringe of the Festival. And from there it transferred to the Traverse, and then to the Citizens, and then into universities, then onto the Bush and the regions, and Broadway and around the world.

Blackout.

Lights up. Kemp stands center stage, he addresses the audience directly.

Lindsay Kemp:

To begin with, I began dancing the same as everybody does, at birth. The only difference was, unlike many other people, I never stopped. In other words, you know, I love movement. Movement gave me such a great pleasure, such a great joy. Dance is really my life. I’ve always said for me Dance is Life, Dance is Living, Dance is Life and Life is Dance. I’ve never really differentiated between the two of them. It’s always been a way of life, a kind of celebration of living.

Well, being born dancing, in Birkenhead, my Father was killed at sea, I mean drowned when, at the beginning of the war, his ship was hit by a German submarine, my Mother took me back to her home town of South Shields, and she enrolled me, at the age of two-and-a-half, in dancing classes because I couldn’t stop dancing.

I just loved it so much, and of course, all the little girls in our street, at that time, all had dancing lessons and all would do this little dance in doorways, and so on, and I began tap-dancing as young as two-and-a-half. I continued dancing and dancing classes and entertaining the neighbor’s children, and during the war years when the bombs were dropping entertaining the neighbors in our air raid shelter.

Straight after the war, going straight up to the local hospital, where I entertained the recovering wounded soldiers, whether they liked it or not, they got my repertoire – all my little dances that had been inspired by movies I’d seen, Carmen Miranda and Marlene Deitrich, and I would sing “Lili Marlene”, I was always an entertainer.

When I reached the age of 10, my Mother thought well, you know, I’ve had enough of this, you know the dancing and theater had become such an incredible passion, I mean I couldn’t think about anything else. This passion fueled by trips to the theater and my Mother taking me to the Christmas pantomimes, where I was totally infatuated with the magic of the theater and its transformations and the theater is a way of life, a very different world form life in South Shields, and I wanted to be in that world.

I always knew what I wanted, you see, really from birth. However, come the age of ten, my Mother thought well he needs is education and I was sent to a boarding school near Reading, the Royal Merchant Navy School, where my mother had hopes for me following in my father’s footsteps and going to sea. But, of course, I didn’t.

Blackout.

Lights up.

Lindsay Kemp is on the telephone. Behind him and to the side, is a school dormitory. Large b&w photographic back projection with about six beds. Lying in the beds are school boys. They have pocket torches with which they use to light a young Kemp’s dance performance.

The young Kemp makes his appearance during Lindsay Kemp’s speech. The young Kemp is dressed in toilet paper, wrapped around his body.

Lindsay Kemp:

At school I survived. It was a very tough school. I survived the bullying and the bullies’ blows by entertaining. You know, with my singing and my dancing, and so on, and putting on little plays.

And that’s when I gave my first performance of Salome.

Young Kemp begins to dance to the lights of the school boys’ torches.

Lindsay Kemp:

For which I was going to be expelled. Not for the sinuousness of the dance, but for the waste of toilet paper, which I’d wrapped around myself.

Spotlight on the young Kemp. He freezes. Lights down. Lights still on Lindsay Kemp.

Lindsay Kemp:

All through school I continued dancing, I danced every day, I danced to entertain, I had my own dancers. Incidentally, that first Salome was very influenced by Rita Hayworth’s Salome, which I’d seen, and also from reading Oscar Wilde, a lot of his fairy stories were an influence on me, but particularly Salome by Oscar Wilde. Years later it was put on the stage.

Blackout.

Lights up. Lindsay Kemp speaks directly to the audience.

Lindsay Kemp:

I always wanted to be an entertainer, you see, I love all forms of theater. I loved variety and circus, and musicals and operetta. I loved it all. And of course now, I have become involved in all aspects of the theater, my dreams, my desires and my intentions, in fact all came true.

Linday Kemp goes back onto the ‘phone, talking to his interviewer.

But I was particularly attracted to the ballet, and at the age of sixteen, before leaving school, I auditioned at the Sadler’s Wells School, which is now the Royal Ballet School. And of course at the age of fifteen, sixteen, I thought I was God’s gift to dance. Of course, I was devastated when I received a letter from the principal saying:

(The words of the letter appear behind Lindsay Kemp, high on a screen. They are typed out word-by-word, as he reads the letter.)

‘Dear Master Kemp, Thank you very much for coming to the audition on September 14th, unfortunately we have to tell you that both I and my board find you both temperamentally and physically unsuited to a career as a dancer. Yours faithfully, Ursula Morton.’

I can see it as clearly now as on that day that I got that letter.

But what if I’d taken any notice? Think what the world would have lost? I’d could have given up and become a coalman…

(Blackout. The ‘phone cuts off. Lights up. Lindsay Kemp talks to the audience. Lights slowly fade during his speech.)

Lindsay Kemp:

I was so determined to become a dancer there was nothing else for me. I did auditions for a load of other dance schools, and drama schools, as I wanted to be an actor as much as being a dancer, and so a painter, come to that, all of those things. I did get a scholarship with the Ballet Rambert School. That was great, but that scholarship didn’t take effect until after I’d had my National Service, you see, because in those days you couldn’t get into university or further education or any jobs until you had done your service for two years.

So, I had to hang around. My Mother moved to Bradford, and worked in a shop, very high class, and that’s where a young David Hockney met me, and David encouraged me to go back to London and try again, and to pursue my dream at all cost.

(Lights out. Lights up.

The telephone rings. Kemp answers it.)

Lindsay Kemp:

Hello, I don’t know what’s the matter. (Pause.) Anyway, we better keep going before it happens again.

I walked into a recruiting office and signed-up for the Air Force on my seventeenth birthday. I couldn’t bear hanging around in Bradford anymore. I met a lot interesting people, the like of which I’ve never met before, very conservative, very right wing, kind of boarding school, very repressed, and I certainly didn’t allow myself to be repressed.

So, I began to do classes at the Rambert during weeks from the Air Force, they gave me special leave so I could train at the Rambert.

Going to the Rambert School was absolute heaven, I was in heaven there. And to meet such wonderful people dancing, other dancers I’d never met before, people with similar dreams and desires as myself, notably Jack Birkett, who later became the Incredible Orlando.

(Lindsay Kemp on Jack Birkett;)

”Jack was Judy to my Mr. Punch, Harlequin to my Pierrot, Titania to my Puck, Herodias to my Salomé, Queen of Hearts to my Lewis Carroll. We shared flats, dressing rooms, boyfriends, bills, good times and bad times, success and failure; a couple of extravagant young dreamers, a couple of aching elders, always entertainers.

Lindsay Kemp:

And Jack said:

Jack Birkett, the Incredible Orlando, appears as an angel and is lowered on a wire from the wings. He is dressed as Eros, with bow and arrow.

Jack Birkett, the Incredible Orlando:

Look.

Lindsay Kemp:

I had another year to do in the forces. Aside No more, because I’d signed on at seventeen for three years. Anyway, Jack said:

Jack Birkett, the Incredible Orlando:

Tell them you’re gay.

Lindsay Kemp:

And I said, To Orlando ‘What’s gay?’

Jack Birkett, the Incredible Orlando:

Tell them you’re gay, dear.

Orlando flies upwards, firing an arrow.

Lindsay Kemp:

Anyway, so, I went to the medical officer and said, ‘I’m gay.’ I had no experience at that time, but I’ve made up for it.

Anyway I was out, there and then, I mean discharged., suffering from what the medical report said was ‘temperamentally ….’

And from there straight back to the Rambert School.

(Kemp addresses the audience.)

I had always put on my own little shows since the age of five years old, and then at boarding school, cajoling other boys to join me and we would put on plays and shows together. And in the forces, during that one year also putting on a lot of plays and performances and so on. And we continued to perform in garages, in fields, in parks, in gardens, wherever we could get a gig in those days, myself and my friends. And bit by bit, that company took on a professional shape so by 1968 or ’69 or something like that, the company as such, the Lindsay Kemp Company made its debut at the Lyric Hammersmith.

(Lights down, then up. On stage the Lindsay Kemp Company performs.)

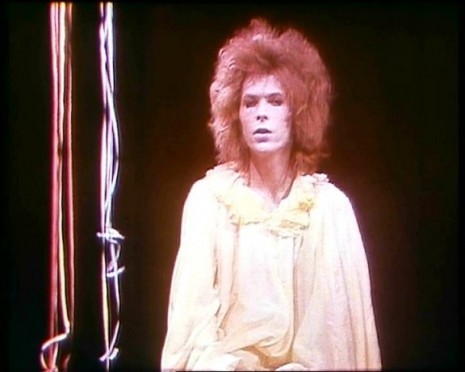

In the late 1960s, Lindsay Kemp met a young musician called David Bowie.

Bowie was on the verge of giving up his pop career, and becoming a Buddhist monk, when he met Kemp. The meeting would change Bowie’s life and career.

David Bowie on Lindsay Kemp:

”It was everything I thought Bohemia probably was. I joined the circus.”

Blackout.

Lights very slowly up as Lindsay Kemp continues his conversation on the ‘phone.

Lindsay Kemp:

I’d heard David Bowie on the radio a few times, and then I was told by an agent’s secretary, they knew someone that I just had to me because they thought I’d really like him a lot, and we’d get on really well together.

They brought him to the theater that night, and I was playing this first track of his record, (Sings.) “When I live my dreams, da-de-da-de-da-da” from his first album. And he was very flattered and then he fell in love, he fell in love with the show and with my work, you know, with my world.

We met backstage afterwards, and we met again the next day, and he began to study with me, I was teaching at the Dance Center in Covent Garden, and we began to create together a little show called Pierrot in Torquoise, for which he wrote the music.

The Looking Glass Murders is not the same as Pierrot in Turquoise, it’s a kind of extension, somewhat of the original Pierrot in Turquoise.

So, Pierrot in Turquoise, this little play we did firstly at Oxford Playhouse, then we took it up to north London, and then onto Whitehaven, and then we split from David. We had a very emotional time together, needless to say, I’m sure you’ve read about that.

(Lights slowly down as archive footage of Kemp and Bowie in ‘Pierrot’ is played on a screen. Paul Gallagher, off stage, reads from Paul Trynka’s biography of David Bowie ‘Starman’.)

Paul Gallagher:

“Kemp in person is engaging and sweet rather than intimidating, his natural extravagance reveling in extraordinary yarns that vary with the telling, as he readily admits. Kemp fell in love with David the first afternoon they spent together, when the dancer spent his time enthusing over his passions, which included, ‘The theater, the music hall, silent movies, the Oriental and ritualistic theater, Kabuki, Jean Genet, the Theater of the Absurd.’ As yet their interests hardly overlapped; it was David’s ‘great sense of humor’ that sealed their relationship, and they would spend much of their time trading impersonations of music-hall stars, or movie icons like Laurel and Hardy.

“Kemp says it was a love affair, as well as a working relationship.”

(The relationship ended on tour, when Bowie was caught with one of the cast.)

“Venturing into the cold night [Kemp] discovered Bowie cuddling Natasha [Korniloff]. ‘I was traumatized,’ says Kemp. ‘Totally destroyed.’

Kemp does admit that a well-publicized subsequent suicide attempt was ‘theatrical’ – an attempt to slash his wrists which produced only surface wounds. ‘Some of those stories are exaggerated. And I’ve given several versions.’ One of the stories has his blood drenching his costume in that night’s performance, ensuring rapturous applause from the crowd.”

(Lights slowly up, back to spotlight on Lindsay Kemp, who lies on the chaise longue, talking into the telephone.)

Lindsay Kemp:

A year later, maybe, Angela, Angela Bowie, came up to Edinburgh where I was performing Flowers, bringing me the record of Ziggy Stardust, and she said:

Angie Bowie appears stage right.

Angie Bowie:

Look, darling, I’d like to…

Lindsay Kemp:

I loved her immediately, loved her, we got on immediately. Her passions, her enthusiasms, her energy, her craziness, all just appealed to me a lot. And of course, I loved the songs on the record, and she said:

Angie Bowie:

Look, would you like to direct it?

Lindsay Kemp:

Angie said:

Angie Bowie:

Come to London.

Lindsay Kemp:

So that weekend I went to London, and I had a meeting with Tony De Freis, because they wanted to hear my ideas about how I would go about staging it as a theatrical production.

And I was very inspired, and I remember to this day standing there in his office and dancing, playing singing the entire show from beginning to end. I mean to say, they were delighted. A few weeks later, we went into rehearsal, and I must say it was a wonderful, wonderful time. It was great and David was incredible to work with. I mean he was so easy, and such a joy to direct, it was great. I got my own way with everything.

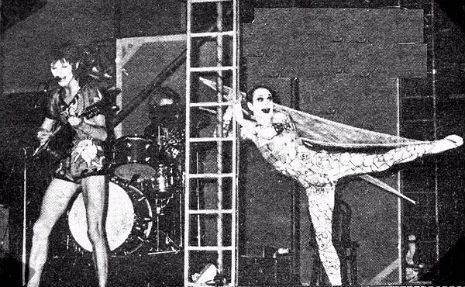

On stage A Young Bowie sings from ‘Ziggy Stardust’ as Kemp and Orlando perform.

Kemp is not only a dancer he has had a successful career as an actor.

Lindsay Kemp:

I acted in plays. Play-making certainly wasn’t encouraged in my kind of boarding school, actors were still considered degenerate, some would say quite rightly.

(Laughs.)

I’d write my own plays and perform in them, one of the first plays I performed in was A Mid-Summer Night’s Dream at school, where I played all the parts.

(Kemp speaks to the audience. Clips of each film runs behind him on screens, each introduced by their title.)

Caption: ‘Savage Messiah’ – Kemp gives a scene-stealing performance as Corkie, who helps young sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brszeka.

Lindsay Kemp:

I got the sack from several establishments. I was working in a hat shop, Dunne’s the Hatters, and I was pirouetting on the parquet floor, when this guy came in and said, ‘No, no, don’t stop, that’s wonderful, wonderful.’ And he said, ‘Hey, look, would you like to come and audition.’ And I got a job, my first professional job, in a play, which was Pirandello, Six Characters in Search of an Author, and from there I did small roles in Shakespeare, and from there I moved in-and-out of dancing, acting and back again, and so on.

And, now, back to the Mercury Theater, where with David, we did the first London performances of Pierrot in Turquoise, Ken Russell was in the audience, and was enchanted by the show, and afterwards he ‘phoned me up late that night and said ‘Would you like to….I’d like to use you in something…’ And then I was up in Edinburgh, doing Flowers at the Citizens, and I got a telegram from him, can you come to London to do a screen test. I went down and I got Savage Messiah, which was my first film, well the first film that I mention.

I remember one night, it was pissing down with rain in a cemetery, at four o’clock in the morning, when I had to push this giant marble, real marble block, in the wheelbarrow, and Russell was not very patient. ‘Wheel the bloody thing straight!’ I’ve never been able to wheel a bike straight, or any bloody thing like that. And Ken’s shouting and being horrible, saying, ‘Think of the Jews crossing the Red Sea.’ ‘I’m not Jewish.’ (Laughs.) Anyway.

Caption: ‘The Vampire Lovers’

Lindsay Kemp:

I don’t even remember doing it. I must have been a bit part, I have no recollection. I was only reminded about it when I saw it on the internet. I was an extra, I really don’t remember. I vaguely remember now, getting in a bus and going to somewhere in Buckinghamshire to a graveyard, and doing a scene.

Caption: ‘Valentino’ – Kemp plays an undertaker.

Lindsay Kemp:

I was picked by Ken Russell, but my role was cut.

(Pause.)

Well, exactly.

(Pause.)

If you blink then you’ll miss me. That’s why I don’t mention it because my part was cut very drastically. Which is what happens in movies, it’s what happens to the best of us.

Caption: ‘Sebastiane’ – Kemp leads a group of dancers with giant papier mache cocks, which ejaculate all over Kemp’s body at the end of the dance.

Lindsay Kemp:

Well, I met Derek Jarman when I was working for Ken Russell, because Derek Jarman did the sets for Savage Messiah, and we became good friends. And of course, he was always very enthusiastic about my work in the theater. And he ‘phoned me up one Monday morning, and he said, ‘Look I’m doing a film about Saint Sebastian and blah, blah, blah, and I’d really like you to play this…’ Well, he wasn’t very specific about my role. So I said, ‘Well, yes I’d love to, but when do we start filming?’ ‘Tomorrow morning.’

And then I had to get my company together, we were doing Flowers again, and that night after the show, we were busy making papier mache giant cocks, which were the cocks featured in the dance. And that was the first film I did with Derek.

It’s lurid. I blush when I look at it. The yoghurt wasn’t very convincing.

Caption: ‘The Wicker Man’

Lindsay Kemp:

Of course, I got The Wicker Man because Robin Hardy had seen Savage Messiah and ‘phoned me up and said, you know, ‘Let’s have dinner.’ And he offered me the role right there and then.

(The movies finish, lights dim back to solo spot on Lindsay Kemp. Blue lighting, back projection of sky and clouds, the sound of the sea lapping on a beach.)

Lindsay Kemp:

Now I am living in Livorno, I have a house somewhere else, near Rome, I love Livorno, it’s by the sea, it’s a seaport, and it’s very me. I’m a poet and Britain is not a land for poets anymore.

(Pause)

I teach students here in dance and in drama.

Teaching has always been a part of what I do, of what I love. Again, that began from when I was very little, and I’ve taught all around the world.

I work a lot with young opera singers, and I direct productions at the opera theater and I’m free to travel. I’ve been asked to direct operas in Italy and in Spain. All around the world really.

So, I still tour around, and I guess with various ballet companies and dance companies.

Over the Christmas holidays I was on tour with a ballet of The Sleeping Beauty, playing the wicked fairy, Parabos, and dancing the Wicked Magician, and the Firebird, all these ballets, when I was a child, I dreamt about appearing in, and here I am seventy years later, and my dreams are still coming true.

Also toured Sicily in The Trojan Women playing Hecuba, and who’d have thought Greek theater in Greek amphitheaters, and I’ve done that.

So, I will continue to live my dream.

(Freeze. Fade slowly to black).

Lindsay Kemp debuts his new production Histoire du Soldat (‘A Soldier’s Tale’) by Stravinsky on 5th May, in Bari, Italy. You can buy tickets for the World Premiere here.

Lindsay Kemp – The Last Dance is a film currently being made by Producer / Director Nendie Pinto-Duschinsky – check here for more information.

Previously on Dangerous Minds

Lindsay Kemp and David Bowie’s rarely seen production ‘Pierrot in Turquoise’ from 1968