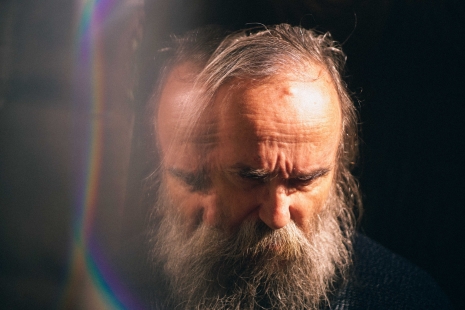

Lubomyr Melnyk portrait by Alex Kozobolis

A few years ago a friend of mine emailed me a YouTube link to the Ukrainian-Canadian pianist Lubomyr Melnyk playing for a rapt audience in Germany. His message said only:

“This guy is a fucking genius.”

He was right, and I was a fan within minutes of pressing play on that clip (see below) and experiencing the overwhelming numinosity of Melnyk’s music, which is both spiritual, and yet highly physical, and not unlike Sufi whirling dervish dancing in the concentration it would require. (It came as no surprise when he mentioned P.D. Ouspensky, the disciple of Gurdjieff, as one of his primary influences during the interview.) His playing can be a blur of passion, laser-like intention, and above all speed. His remarkable FLOOD of sound and cascading harmonics is unlike anything you are ever likely to have heard a piano sound like. Melnyk is considered the world’s fastest pianist, and has been timed playing nineteen and a half notes per second with each hand. The human ear cannot entirely take that much information in and make perfect sense of it, and so the music starts to twinkle and BREATHE and zen you out like a mantra. Although he admits to being influenced by Terry Riley and Steve Reich, he’s the exact opposite of a minimalist. The succinct opening paragraph in Melnyk’s Wikipedia entry reads:

Melnyk is noted for his continuous music, a piano technique based on extremely rapid notes and complex note-series, usually with the sustain pedal held down to generate harmonic overtones and sympathetic resonances. These overtones blend or clash according to harmonic changes. Most of his music is for piano, but he has also composed chamber and orchestral works. His piano music requires a special technique, closely related to the martial arts, and is too complex and difficult for any concert pianists to play. Because of his lifelong devotion to the piano, he has been called “the prophet of the piano.”

Melnyk told one interviewer:

What I do on a piano, nobody did before me. Because it is impossible to do it physically. It is something like a miracle. I don’t boast, God gave me this possibility. It is not me, it is not me who did it. I don’t wear a special royal dress and say that “I am the piano king because I do it.” No, it is all a gift from God. And I do it. People don’t understand that it all – from my spirit to fingers on keys and those sounds – is a whole life.

After this astonishing new musical discovery, I raced off to Discogs immediately to grab whatever I could find of Lubomyr Melnyk on vinyl. Solo piano sounds so amazing on wax, but the problem was one of scarcity. What existed on vinyl went for top dollar and some of it was only ever issued privately on cassette in the first place, so good luck finding those (most of his releases have zero for sale on Discogs). In recent years as interest in Melnyk’s fascinating music has risen around the world, his work has been issued by the Erased Tapes label and is becoming much easier to find. His latest release, Fallen Trees, was inspired by travelling Europe by train. Riding through a dark forest full of recently felled trees, this sad sight was his muse: “They were glorious,” he says. “Even though they’d been killed, they weren’t dead. There was something sorrowful there, but also hopeful.”

On January 24, celebrating his 70th birthday (which will be on December 20th), Lubomyr Melnyk will play a concert at London’s EartH venue in Hackney, with special guests Peter Broderick and Hatis Noit. (Get tickets here.)

I asked the maestro a few questions via email.

Richard Metzger: Where did you first “hear” your music? In the sense that you will often hear musicians say that a repetitive rhythm might come from having worked for a time in a factory. Captain Beefheart famously found a “floppy” drumbeat in his car’s windshield wiper. Your piano style is so distinctly your very own music, that once someone has heard you play, you could never be mistaken for anyone else. Where did you first “hear” it? What made it possible?

Lubomyr Melnyk: It is funny you mention these things because I have been told by close friends that I am in fact a true drummer! The beats are just pouring out from my mind and my fingers. The origins of Continuous Music are indeed drumming with various rhythms appearing and various harmonics and upper frequencies. All my life I have heard the phenomenal sounds of melodic rhythms in machinery, what wonderful wonderful sounds they are! And this has been a secret source of my music. But only in a secret dimension kind of way. Without the power of drumming in my body and mind, this music would never have been born.

How do you define your “Continuous Music”?

You might as well ask me to define time and all five dimensions (there are more by the way, I just said five for now because it points us in the right direction…) In other words, it is transdimensional and metaphysical ability, similar to kung fu or Tai chi, for example; it’s not possible to separate the music from the technique, like you can not separate the “sound of the sword” from the body of the master. They are one and so is Continuous Music one with the being of the pianist. This might not explain it very well, but it is really quite impossible to describe. Continuous Music is a vast river flowing inside your soul and this river contains the four winds and it contains ice and it contains water and it turns to stone when you so wish.

Portrait of the artist as a young man

I’ve read that one formative aspect of your career was accompanying a dance troupe. How did playing for bodies in motion influence your style?

This is a super important element in the birth of Continuous Music. The master dancer Carolyn Carlsson was the inspiration for these dancers and the basic fundamental and pervading aspect of the classes was transcendent. They strove to transcend all time and all space and they inspired me to travel with them. You can not imagine how it was a special bubble of existence we experienced there, in 1972, in the attic of the Paris Opera high above the city, with huge windows and old old wooden floors with a grand piano. Me and these magnificent beings, the dancers.

This brings to mind John Cage, of course. You seem like someone who would take John Cage very seriously. Are you a student of his work and of his thought?

I loved John Cage and everything he did and created and wrote. His books were of great importance to my musical thinking and in fact, it was John Cage who, at our tea-meeting at his home in New York, pointed me into the direction of a certain German transcendental composer of the 1930s whose musical language became the foundation of Continuous Music… the constant maintaining of harmonies and changing them very slowly so yes, he had an enormous effect on my pianistic development and of course, his interest in Zen thinking was another great influence.

What, or who else, has been an influence on your work?

Ah, what a list this would be! Let’s start with hippiedom and then of course, all the books the hippies read. My university studies of philosophy because, in fact, I wondered why intelligent professors ran to the hills when they had to confront Zeno’s paradoxes. And then musicians like Ravi Shankar, John McLaughlin, Jimi Hendrix who was on the guitar what Carolyn Carlson was to dance, and Ouspensky the philosopher. The list to goes on and in fact, it never ends. Continuous Music is a wonderful physical activity that never stops to grow and the beauty of the piano never ends. Never!

I enjoy watching your performances on YouTube where you can catch a glimpse of the audience—like your performance of “Illorium Nr. 03B” on German TV—and they seem to have been led into meditative states by your playing. It’s interesting to note that people react similarly to La Monte Young’s piano, and yet he and you are doing the exact opposite thing musically—obviously there is nary an arpeggio in his repertoire—and yet the end result on the listener is one that leaves one deep in thought, and unavoidably so. You are a sort of wizard. Your method of charging the atmosphere and the air around you is remarkable. What is your aim, in a magical sense, to impart to your audiences?

I want the river of sound to carry people along a world of beauty and deeper thought, a time where time stops, a place that has no space, a world that is more real than this world upon which we walk so that their souls will be strengthened and find a meaning in their life that is good and beautiful. Music exists to lift us up, up from the miserable mud of our hardships. It is a great gift and we should be grateful every minute of every day that we can hear music. It is really not so easy to hear it actually.

“Illorium Nr. 03B” performed live for German television in Hamburg

A fascinating short portrait of Melnyk culminating in a performance of “Butterfly” in Copenhagen.

“The Remnants of a Man (for two pianos)”

“Cloud No. 81”