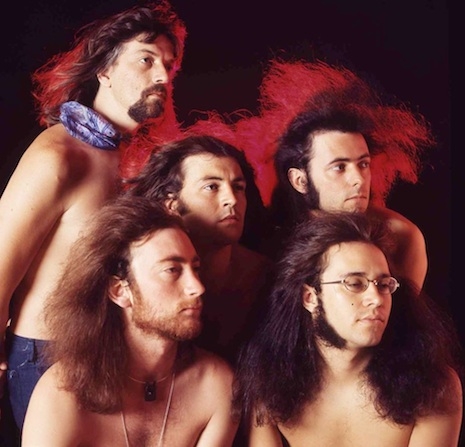

Deep Purple, topless

There was a point back in the 1970s that whenever you went into a guitar store there was always some dude flicking his locks and playing the familiar plodding riff from Deep Purple’s “Smoke on the Water.” Well, either that or “Stairway to Heaven” depending on the taste of who was playing. These guys were either shop staff or some kid dreaming of a future rock career. When I bought my first and only guitar the assistant did in fact strum out a few blasts of “Smoke on the Water” to show me just how it was done. That kinda ruined it for me, I have to admit. I was more the Bonzo-Django-Benny Hill kinda player, which might explain my taste in music but doesn’t excuse my lack of any musical talent whatsoever. Least played, soonest mended. I eventually traded my guitar for a portable typewriter from a Bowie fan who had slavishly typed “I Love David” all over its ribbon.

If you hung around long enough listening to that dude riff on “Smoke on the Water” he would also probably tell you why Deep Purple were better than Led Zeppelin—because they were “proper” musicians who had performed “your actual” Concerto for Group and Orchestra with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra at the Royal Albert Hal, London in 1969. And why the recent incarnation of the band was better than the first—because (again) they were “proper” musicians not just pop stars, musicians who had honed themselves to the pursuit of musical excellence. Or something like that.

He would also undoubtedly tell you how “Smoke on the Water” was based on a very real fire at the Montreux Casino during a Frank Zappa concert in 1971, where the venue was burnt to the ground. Depending on which version you heard, the fire was caused by either a flaregun fired by a member of the audience, or possibly a firework, or possibly by a “boy throwing lighted matches in the air, and one of them got stuck on the very low ceiling.” Whichever, the fire started and quickly engulfed the building.

Founder of the Montreux Jazz Festival, Claude Nobs was at the venue that fateful night and helped rescue quite a few of the audience from death. He was also key in persuading Deep Purple not to “scrap” “Smoke on the Water” from inclusion on their mighty album Machine Head. As Nobs recalled:

Deep Purple were watching the whole fire from their hotel window, and they said, “Oh my God, look what happened. Poor Claude and there’s no casino anymore!” They were supposed to do a live gig [at the Casino] and record the new album there. Finally I found a place in a little abandoned hotel next to my house and we made a temporary studio for them.

One day they were coming up for dinner at my house and they said, “Claude we did a little surprise for you, but it’s not going to be on the album. It’s a tune called ‘Smoke On The Water.’” So I listened to it. I said, “You’re crazy. It’s going to be a huge thing.” Now there’s no guitar player in the world who doesn’t know [he hums the riff]. They said, “Oh if you believe so we’ll put it on the album.”

It’s actually the very precise description of the fire in the casino, of Frank Zappa getting the kids out of the casino, and every detail in the song is true. It’s what really happened. In the middle of the song, it says “Funky Claude was getting people out of the building,” and actually when I meet a lot of rock musicians, they still say, “Oh here comes Funky Claude.”

Deep Purple were originally called Roundabout—when the band was just a concept conjured up by Searchers drummer Chris Curtis in 1967. Curtis shared a low rent apartment with young musician Jon Lord, who was earning his spurs playing with many different bands—including a tour with the Flowerpot Men (best known for the song “Let’s Go to San Francisco”). Curtis explained his idea of the Roundabout being a group of three people—Curtis, Lord and a guitarist named Ritchie Blackmore—around which other band members would hop on and off when required. Not much happened. Lord toured. And Blackmore never turned up for a meeting about this “concept band.” That is, until Curtis took way too many drugs, covered the apartment in aluminum foil—reasoning it stopped all the good vibes escaping, and upped and left Lord with rent due, no band, and not much of a future.

That very day, the fabled Ritchie Blackmore turned up at the door to discuss Roundabout with Curtis. Instead, he and Lord discussed forming their own band, which eventually became Deep Purple. The name came from the song “Deep Purple”—a favorite of Blackmore’s aunt. Other possible band names were Concrete God, Orpheus and Zephyr.

In a way, Deep Purple did follow the concept Curtis had imagined for the band. Deep Purple Mk I with Rod Evans as lead singer verged on the almost poppy. This version of Deep Purple released three albums and had hits in America—most successfully their cover of Joe “I Never Promised You A Rose Garden” South’s song “Hush”—but still they made little impact in their homeland.

At the time, Lord and Blackmore were both content to have the band seen as being like Vanilla Fudge. This was all to change after Blackmore instigated the removal of Evans and bassist Nick Simper having them replaced by Ian Gillan as singer and Roger Glover as bassist—both from band Episode 6. At last, Deep Purple had a hard rock edge and a direction to move in.

Deep Purple Mk II was the most successful and most popular incarnation of the band. From the release of the Concerto for Group and Orchestra in 1969, through Deep Purple in Rock (1970), Fireball (1971) and Machine Head (1972), the band produced some of the best and most influential albums of the 1970s.

Inevitably, internal disagreements caused Blackmore to get rid of Glover, which led Gillan to quit. An then an unknown singer called David Coverdale was brought to replace Gillan with Glenn Hughes on bass. This Deep Purple Mk III moved in another direction which led to more splits and the band’s eventual disintegration in 1976. Since then, Deep Purple Mk II reformed in 1984, and it’s variation on this line-up (Lord died in 2012) that continues to this day. This video of Deep Purple playing in New York in 1973 has been been around the block a few times—but it highlights in twenty or so minutes just how truly great Deep Purple were at their height and how influential they were to the development of hard rock and heavy metal—and not just to dudes playing guitar in music shops.