“This is where all my dreams become realities, and some of my realities become dreams.” American artist and banjo player Harper Goff (1911-1993) was a man of many talents with an extraordinary imagination. He set the standard for camouflage colors during WWII, laid the foundation for the Steampunk revolution, conceptualized Disneyland alongside Walt Disney, and created the unforgettable set for Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory. However, due to issues with his union card Harper remains uncredited for nearly his entire life’s work.

Living in New York City, Harper Goff worked as a magazine illustrator for Collier’s, Esquire, and National Geographic. Harper’s techniques as well his imagination were groundbreaking even early on. In his paintings, he often refused to use modeling talent but instead incorporated real life village citizens into the details of his colorful works. Friends, family, and neighbors traveled to exotic beachfront estates and vacation spots around the world courtesy of Harper Goff, half of them never even realizing it. During his service in WWII while Harper was working on a do-it-yourself painters kit he was approached by the U.S. Army to develop a set of paint colors that would become the new standard for camouflage. Near the end of the war, he was transferred to the U.S. Navy where his razzle dazzle technique helped confuse the silhouettes of ships taking the idea of camouflage to a whole new level.

When Harper moved to California to work for Warner Brothers Studios he became a set designer on films such as Casablanca, Sergeant York, Charge of the Light Brigade, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and the Errol Flynn classic Captain Blood. It was while working as an Art Director on Kirk Douglas’ The Vikings that director William Wyler saw in Goff a “character type” and began casting him as an actor. “I showed up wearing a beard, they figured I’d make a good Nordic,” said Harper, who would end up heaving a battle axe at his blonde viking wife in the film. Harper made dozens of appearances in film and television as an actor much to the amusement of his real life blonde wife Flossie. In 1951, while shopping in a London model railroad shoppe Harper had a chance encounter with Walt Disney when they both expressed a mutual interest in purchasing the same model train.

“He turned to me and said, ‘I’m Walt Disney. Are you the man that wanted to buy this engine?’ Well, I almost fell over. He asked me what I do for a living, and I told him that I was an artist. Walt said, ‘I’ve heard of you, but I can’t recall where.’” It turned out Walt Disney had seen some of Harper’s illustrations in Esquire magazine and had always admired them. Disney said, “Give me a call me when you get back to the States.” Ultimately Walt bought the locomotive and hired Harper to illustrate the earliest concept artwork and renderings for his proposed “Mickey Mouse Park” (originally intended to be constructed in Burbank). “I liked the idea of working with Walt Disney, and when I called him he began to explain his idea for a kiddie-land near the Studio — perhaps with a steam train connected to Traveland across the L.A. River. He wanted to build something adults could enjoy along with their children.”

Walt sent Harper on a three-month “information gathering” journey to amusement parks all across the United States. “They were dirty places and it was hard to imagine what Walt had in mind creating. I said to him when I got back, ‘Walt, I don’t think this type of environment is what you want,’ and he replied, ‘Mine will be immaculate and the staff will be young and polite,’ then I realized he could do it.” Orange County was eventually chosen as the site for Disneyland and Harper, who was dubbed the “Second Imagineer” envisioned the look and feel of the theme park. Harper used his hometown of Fort Collins, Colorado as the main influence for Disneyland’s City Hall, and his Art Director experience on the film Calamity Jane to design the Golden Horseshoe Saloon.

Harper Goff’s influence on the Adventureland portion of the theme park cannot be overstated, particularly on the ride the Jungle Cruise. In Harper’s own words: “We began to think of hippos and other animals which could be operated without wires and still have animated elements. We brought in Bob Matte, who later created the shark for Jaws to engineer the original animals. I also worked with Bill and Jack Evans on buying expeditions for the landscaping. We would call cities to see if they were tearing out trees for improvements and go and buy them — we got many that way.” While making trips back and forth between Burbank and the Evans and Reeves Nursery in West L.A. they’d pass a house in Beverly Hills that had spectacular tree in the front yard. Harper and Jack believed it’d be the perfect finishing touch to the Jungle Cruise ride. “Finally, I thought what have we got to lose, and I had Jack Evans stop while I went in to ask the people if they would consider selling it. I told the owner we would replace it with a flowerbed or anything they wanted and surprisingly enough the owner told me yes — it was blocking the sunlight and view coming through his windows and we could just come and take it away… it was the tree that went around the original Burmese Temple, and we got it for nothing.”

Alongside Imagineer Ken Anderson, Harper Goff began creating concept art for a “walk-through” haunted house attraction at Disneyland, originally to be situated at the end of Main Street, U.S.A. by turning down a winding path. The mysterious “old house on the hill” was inspired by haunted houses from all across the country. Anderson and Goff originally envisioned the house as run-down and decrepit, but when they presented Harper’s exterior sketches to Walt he did not agree. Walt insisted that the house look nice to match the pristine appearance of the park. He didn’t want people to think that Disneyland wasn’t taking care of its attractions, and said: “We’ll take care of the outside, and let the ghosts take care of the inside.” The attraction took nearly 20 years to complete and was renamed The Haunted Mansion before being moved from Main Street to the New Orleans Square section of the theme park.

It was around this time that Harper, who had been playing banjo for about 30 years, formed a musical friendship with fellow Disney Legends Ward Kimball (trombonist) and Frank Thomas (pianist). “I met Ward Kimball at Disneyland and he asked me to join the Firehouse Five Plus One after he heard me play banjo,” Goff recalled. “Then it became the Firehouse Five Plus Two.” Harper picked up a banjo that was laying next to his fireplace and strummed a few notes of “Firehouse Stomp”—better known to music lovers as the theme from “Under the Double Eagle.” The Firehouse Five Plus Two toured the country and released thirtreen LP’s on Good Time Jazz between 1949 and 1970, the label responsible for the Dixieland jazz and New Orleans sound revival. The Firehouse Five Plus Two also appeared in several films and national television specials.

When Disney produced Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, its first ever live-action film, Harper was brought on board to create some of the finest stylistic effects ever to appear on the big screen. Goff’s vision of Captain Nemo’s baroque Nautilus vessel differed drastically from the one described in Verne’s book and has since been credited as the foundation of the increasingly popular Steampunk phenomenon. It’s known that many of the influential steampunk authors of the ‘70’s and ‘80s were more inspired by the visual impressions left by 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and the cinematic adaptations of Verne’s novels that followed in its footsteps than they were the original novels themselves. Goff told Disney he imagined that Captain Nemo put the Nautilus together “hastily and roughly” using “only material available, salvaged from wrecks.” As a result, the Nautilus design with its nineteenth-century ironclads and mosaic of metal plates held together by thousands of rivets became the very first visual encapsulation of the steampunk aesthetic. In 1955 when 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea won an Oscar for art direction, the Art Directors Union had created a bylaw within the Academy of Motion Pictures which dictated that only art directors in the union were eligible to win the award. Sadly, Harper Goff didn’t have a union card at the time so the Oscar was instead awarded to his assistant John Meehan. Years later it was reported that the Academy eventually (and discreetly) sent a plaqueless Oscar statue to Mr. Goff as a well-intended gesture to partially correct what is considered a significant oversight over a man who director Richard Fleischer said “designed everything, but got nothing.”

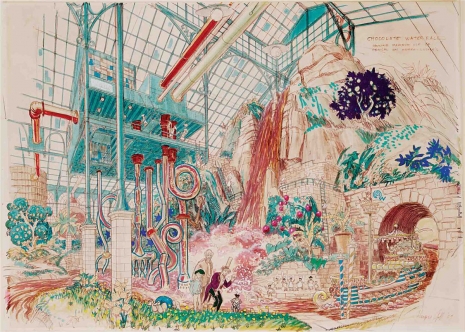

It was Harper’s work on the 1966 20th Century Fox motion picture Fantastic Voyage (a visualized trip through the inner body starring Raquel Welch) that caught the attention of director Mel Stuart, who was working on a film adaptation of British children’s author Roald Dahl’s 1964 novel Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. At the age of 60, with his union card issues finally resolved, Harper at long last received a proper “Art Director” credit for his work on the low budget 1971 cult classic Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory. After months of location scouting in Europe (a tour which included the Guinness brewery in Ireland, and a real-life chocolate factory in Spain) Harper finally found the perfect location to house his enormous chocolate factory set: Bavaria Film Studios in Munich, Germany. Director Mel Stuart remembers in his book Pure Imagination: “Harper Goff was the ideal man to create this fantasy. I felt confident he could create a special trip though a most unusual candy factory. I knew that whatever he concocted was not going to be conventional.”

The construction team got to work on the set which included a chocolate riverbed and waterfall, built alongside a large platform that covered the entire length of the studio’s soundstage. “Harper and his crew covered the grounds with a fantastic carpet of brightly colored shapes containing candy. There were giant mushrooms filled with whipped cream, chocolate-bearing trees, and a host of other delights.” Many of the props on the set were edible, however, one of the most memorable props was not. “The teacup that Gene Wilder bites off at the end of the song ‘Pure Imagination.’ It was made of wax. When Gene took a nibble of the cup during a rehearsal, he had to spit it out. We quickly made a substitute out of sugar.” When director Mel Stuart began shooting the film he deliberately prevented the children and their parents from seeing the Chocolate Room set until the day they actually shot the scene. “I wanted to film their reactions as they saw the room for the first time.” While the set looked completely amazing, its very size and the laborious machinery needed to make it work properly caused production problems during the filming. Problems also arose when the chocolate river became smelly and bubbly. “Hank (Wynands the construction coordinator) found that a combination of salt conditioner and some chemicals took care of that problem. The river looked great, but it felt like what it was: cold, dirty water.”

Next on the agenda was the construction of the Inventing Room, which Stuart envisioned as a wacky inventors laboratory, with Rube Goldberg mechanisms and a hodgepodge of unusual contraptions whose purpose in candy making only bewildered the audience. Harper sent his construction crew into Munich searching junkyards, bakeries, and automobile dealers for discarded machinery, tin funnels, and any sort of odds and ends that would serve as raw materials for the set. “When the crew was assembling the Inventing Room set, I discovered that the invention that creates Violet Beauregarde’s gum was planned as an enclosed piece of machinery. I asked Harper if he could find a way to make the operation of the machine a visual experience for the audience. Harper agreed, and he ended up surpassing himself. The parts were made of unlikely objects, including an actual beehive that made honey, boxing gloves that pounded flour, and a tomato squashing machine—a perfect example of making dreams become realities. Paris Themmen who played Mike Teavee, lifted the lid on the beehive one day and released some bees. As life mirrored one of the morals of the movie, one of the bees stung him.”

Harper’s incredible body of work continued outside of Hollywood motion picture studio system. He designed the structural globe fountain centerpiece for the 1964-65 New York World’s fair, a series of VIP hotel suites for the Houston Astrodome, and an oil painting series for Harrah’s lakefront resort in Tahoe. In the early 1980’s Harper returned to Disney to devise EPCOT’s World Showcase, and he personally worked on the Japan, Germany, and United Kingdom pavilions. Tokyo Disneyland was his last project before retiring to his beautiful three bedroom home at 2333 South Vía Lazo in Palm Springs. Harper Goff died of heart failure on March 3rd, 1993, just two weeks shy of his 82nd birthday. He was survived by Flossie Newcomb, his wife of more than 60 years, and posthumously named a Disney Legend. A window in Adventureland honoring his legacy reads “Oriental Tattooing by Prof. Harper Goff” with the lower pane simply displaying the words “Banjo Lessons.”

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

Pure Imagination: Behind-the-scenes photos of ‘Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory,’ 1971