The writer Max Frisch once wrote that an author does nothing worse than betray himself. In that, a work of fiction reveals more of a writer’s thoughts, tastes, and secrets than any work of biography.

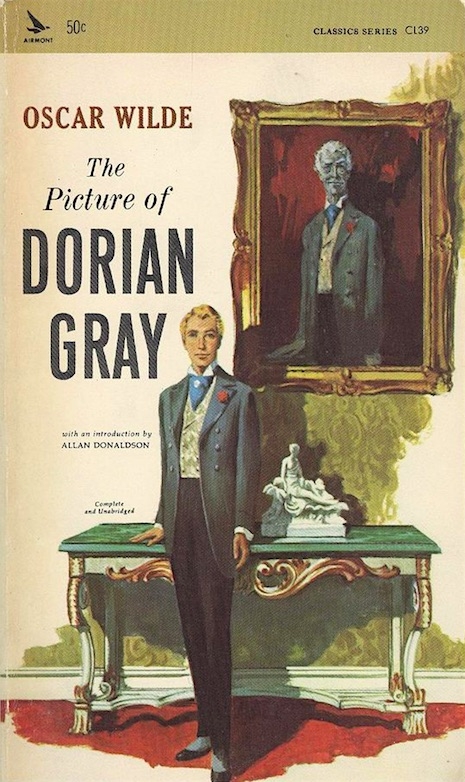

This, of course, may not always be the case, but for many it is true. Like Oscar Wilde, whose novel The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891) revealed more about his tastes and thoughts and secret lifestyle than he ever ‘fessed-up to in public—as he once admitted in a letter to the artist Albert Sterner in 1891:

You’ll find much of me in it, and, as it is cast in objective form, much that is not me.

The parts that were thought to be Wilde—the story’s homoerotic subtext—led the press to damn the book as morally corrupt, perverse, and unfit for publication.

As for the parts that were not Wilde, they revealed some of the people who in part inspired his story, in particular, a poet called John Gray (1866-1934), who was one of the Wilde’s lovers. Gray later loathed his association with the book and eventually denounced his relationship with Wilde and was ordained as a priest.

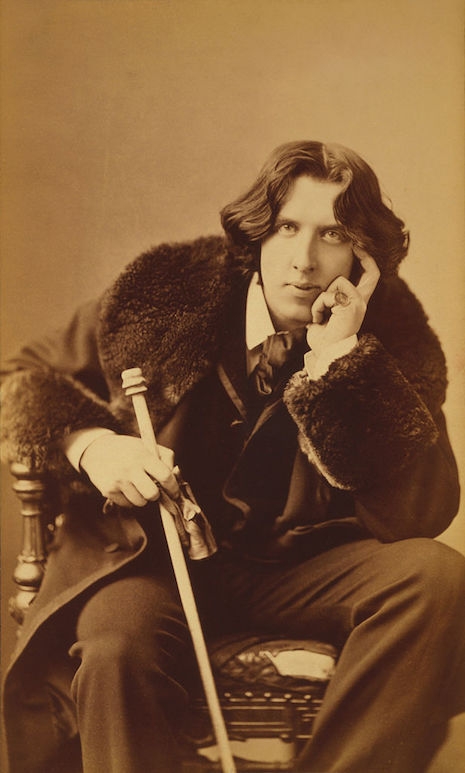

Wilde thing: A portrait of Oscar in his favorite fur coat.

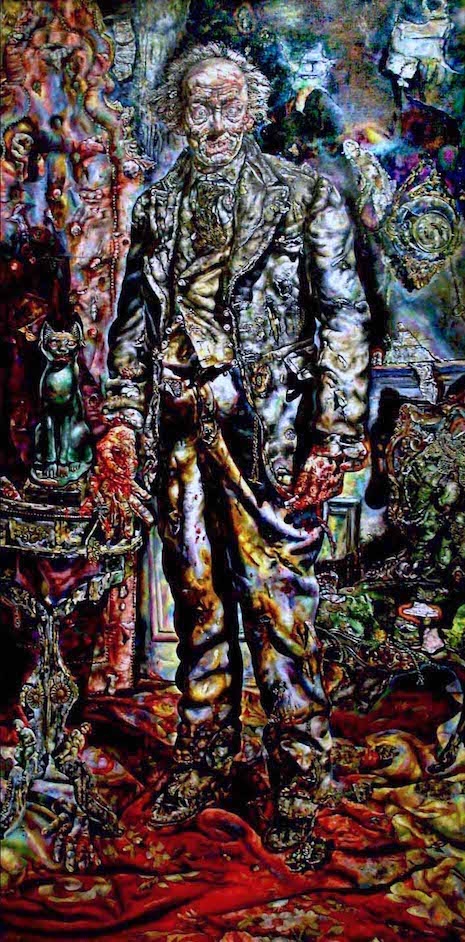

The Picture of Dorian Gray tells the story of a distinguished young man, Gray, whose portrait is painted by the artist Basil Hallward. On seeing the finished picture, Gray is overwhelmed by its (or rather his own) beauty and makes a pact with the Devil that he shall stay forever young with the painting grow old in his place. In modern parlance, consider it Faust for the selfie generation. Gray then abandons himself to every sin and imaginable depravity—the usual debauches of sex, drugs, and murder, etc.—in order to “cure the soul by means of the senses, and the senses by means of the soul.” As to be expected, this has catastrophic results for Gray and those unfortunate enough to be around him.

Wilde disingenuously claimed he wrote The Picture of Dorian Gray “in a few days” as the result of “a wager.” In fact, he had long considered writing such a Faustian tale and began work on it in the summer of 1889. The story went through various drafts before it was submitted for publication in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine. Even then, Wilde contacted his publisher offering to lengthen the story (from thirteen to eventually twenty chapters) so it could be published as a novel which he believed would cause “a sensation.”

It certainly did that as the press turned on Wilde and his latest work with unparalleled vehemence. The critics were outraged by the lightly disguised homosexual subtext, in particular, Wilde’s reference to his secret gay lifestyle:

...there are certain temperaments that marriage makes more complex…They are forced to have more than one life.

The St. James’s Gazette described the tale as “ordure,” “dull and nasty,” “prosy rigmaroles about the beauty of the Body and the corruption of the Soul.” And went on to denounce it as a dangerous and corrupt story, the result of “malodorous putrefaction” which was only suitable for being “chucked on the fire.”

One critic from the Daily Chronicle described the novel as:

...a tale spawned from the leprous literature of the French Decadents—a poisonous book, the atmosphere of which is heavy with the mephitic odours of moral and spiritual putrefaction…

While the Scots Observer asked: “Why go grubbing in the muckheaps?” and damned the book as only suitable “for the Criminal Investigation Department…outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph boys.”

The last remark related to the “Cleveland Street Affair” of early-1890, in which young telegraph boys were alleged to be working as prostitutes at a brothel on Cleveland Street. It was claimed the government had covered-up this notorious scandal as the brothel was known to be frequented by those from the highest ranks of politicians and royalty.

Little wonder that when Gray was publicly identified by the Star newspaper as “the original Dorian of the same name” he threatened to sue for libel. Gray asked Wilde to write a letter to the press denying any such association. Wilde did so, claiming in the Daily Telegraph that he hardly knew Gray, which was contrary to what was known in private. The Star agreed to pay Gray an out of court settlement—but the association was now publicly known.

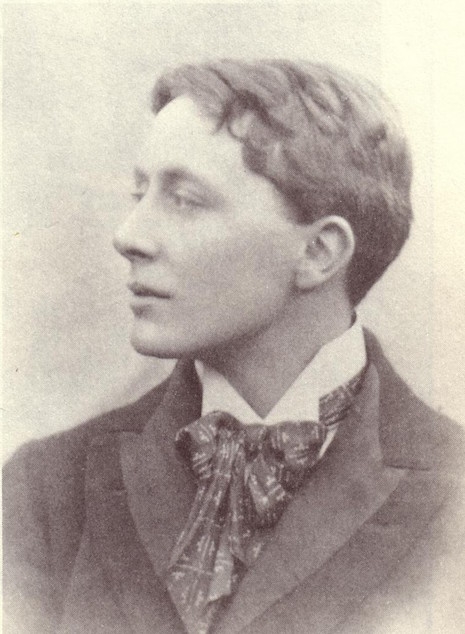

John Gray: ‘The curves of your lips rewrite history.’

John Gray was the eldest of nine children born into a working-class family in Bethnal Green, London. His father was a wheelwright and carpenter. At fourteen, Gray was apprenticed as a metal worker at the Royal Arsenal involved in the production of munitions. However, he held secret ambitions to better himself and become a poet. He enrolled in night classes where he studied art, music, and languages. He then joined the civil service in 1882 and went onto study at the University of London before joining the Foreign Office as a librarian.

Gray started writing poetry and gravitated towards London’s bohemian art scene where he became friends with the artist Aubrey Beardsley, the poet Edward Dowson, and Oscar Wilde. Gray was an incredibly beautiful man. It has been claimed that even in his mid-twenties he had the sensuous beauty of a fifteen-year-old.

Gray first met Wilde in the summer of 1889 at a party in a Soho restaurant. Wilde was immediately besotted by Gray’s beauty. For his part, as noted by George Bernard Shaw, Gray was “the most abject of Wilde’s disciples.”

Whether Gray was the sole influence in the creation of “Dorian Gray” is a moot point. However, the conjunction of their first meeting in the summer of 1889 when Wilde started work on Dorian Gray around the same time does suggest some form of artistic cross-pollination. Moreover, Gray signed his letters to Wilde under the alias “Dorian.” Gray also later recalled receiving a letter from the playwright which stated:

The world is changed because you are made of ivory and gold. The curves of your lips rewrite history.

John Gray and Marc-Andre Raffalovich with a friend circa 1932.

Wilde was so smitten by Gray he offered to pay for the publication of a book of his poems called Silverlight. This volume was eventually published in 1893 but by then Wilde had reneged on his offer and Gray had been usurped in his affections by a new beau—-Lord Alfred Douglas.

Gray was almost destroyed by Wilde’s rejection. He told friends he had seriously considered suicide but was saved by the attentions of another man—Marc-André Raffalovich.

Raffalovich was an exceedingly rich gay Jewish Russian emigre, best-known for his patronage of the arts—publishing essays, books, poetry, and sponsoring artists. Raffalovich collaborated with Gray on series of plays. Apart from their love for each other and their literary ambitions, both men held deeply religious convictions. Gray had converted to Catholicism in 1890 and encouraged Raffalovich to follow suit, which he did in 1896. Then in 1889, Gray entered the Scots College in Rome and was ordained a priest.

How their relationship continued after Gray’s ordination is up for debate. Raffalovich supported Gray and moved with him to Edinburgh when Gray was appointed as the priest to St. Patrick’s church in the poor and deprived district of the Cowgate.

Meanwhile, Raffalovich became established as a patron of the arts in Edinburgh. He still wanted more for Gray. He, therefore, approached the diocese in Edinburgh with the offer to pay for the building of a new church in the wealthy, middle-class district of Morningside under the sole proviso that Gray was appointed its priest. The Catholic Church agreed and Raffalovich stumped-up £5,500 to pay for the building of St. Peter’s church on Falcon Avenue, Morningside.

Gray and Raffalovich maintained their close relationship for the remainder of their lives together. Raffalovich died in February 1934. Gray in June the same year. Most people who pass by St. Peter’s church today would hardly think this is the church that was built for the man who had once been Oscar Wilde’s lover and in part the inspiration for Dorian Gray.

’Dorian Gray’ (1943) by Ivan Albright.

Images via WikiCommons.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

Meet the woman who photographed Frida Kahlo, the Kennedys, Elizabeth Taylor, fashion & war

Meet Anita Berber: The ‘Priestess of Debauchery’ who scandalized Weimar Berlin

Meet the original Nirvana: A pioneering sixties psychedelic rock duo

Meet Craig Smith, L.A. pop-folk golden boy turned lost psychedelic genius, then tragic acid casualty

Meet the Swedish mystic who was the first Abstract artist

Meet the wild child ‘Tiger Woman’ who tried to kill Aleister Crowley