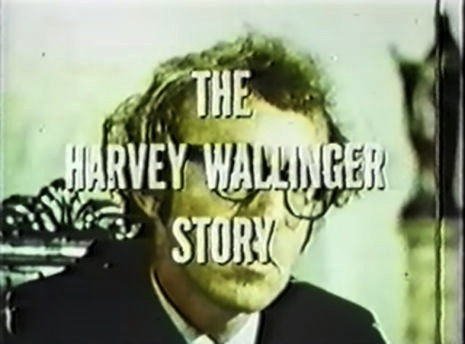

By the time Woody Allen made “Men of Crisis: The Harvey Wallinger Story” in 1971/72, messing with found footage as well as the documentary form had become old hat for the restlessly experimental moviemaker. After all, his feature-length experiment of fusing new dialogue to existing footage, What’s Up, Tiger Lily? has been released several years earlier, in 1966. His first faux documentary (and one of the first “mockumentaries” in cinema history), Take the Money and Run, had come out in 1969.

“Men of Crisis” seems more than a little perfunctory. Wallinger is clearly a substitute for Henry Kissinger, but there’s really nothing about the Kissinger-Nixon relationship (as it was perceived in 1971) that was all that funny; the humor lies in the notion of Woody being “the second most powerful man in America.” The movie was supposed to be an hour long, but the final product delivered by Woody ran only 25 minutes long. Clearly the subject of the reprehensible Nixon presidency (pre-Watergate, of course) did not really animate Woody. The movie feels a lot like an extended sketch from HBO’s “Not Necessarily the News” in the 1980s, which usually juxtaposed perfectly normal footage of e.g. Ronald Reagan with concocted footage to produce a ridiculous effect. One thing that makes “Men in Crisis” noteworthy is that it marks the first occasion Woody Allen and Diane Keaton worked together on a movie. Keaton plays Wallinger’s ex-wife, “Renata Baldwin, who attends Vassar College, where she studies to be a blacksmith.” (As a Vassar alum, I’m pretty fond of this joke.)

Richard Nixon had a knack for annoying liberal elites that was very similar to that of George W. Bush. Woody Allen was never the most political of artists; even when dealing with politics, such as in “Men of Crisis” or Bananas, the essentially surrealist nature of his humor tends to run roughshod over any particular satire. One gets the feeling, watching “Men of Crisis,” that Woody has contempt for Nixon mainly because he’s not highbrow enough (witness the gag about Nixon and Agnew knowing “almost” all of the numbers from 1 to 10).

PBS was worried about running the program, they were right to be. After all, the Nixon administration was so famously thin-skinned that Nixon personally exerted pressure on Jack L. Warner to remove the song “Cool, Cool, Considerate Men” from the movie 1776 because it seemed to poke fun at conservatives. (You can watch the musical number on recent reissues of the movie; it seems pretty harmless.)

If nothing else, the cancellation of “Men of Crisis” had the effect of cementing Woody’s determination to work in feature movies, where outside interference could be minimized. He said afterwards that the incident had reinforced his preference to “stick to movies.” According to The Vanishing Vision: The Inside Story of Public Television by James Day, the cancellation of “Men of Crisis” went down as follows:

The politically charged atmosphere of the early seventies should have warned those of us at NET that the times were hardly propitious for political satire—and certainly not on the public medium. But so eager were we to bring an element of lightness, a laugh or two, to public television’s overarching solemnity that we unhesitatingly accepted Woody Allen’s offer in late 1971 to produce a special. We didn’t even pull back after learning that he intended to use the show to satirize the Nixon White House. Allen approached us after having produced two prime-time specials for the commercial networks, fully expecting the public medium to give him greater artistic license to write and perform the kind of humor for which he is justly celebrated. He was wrong.

…. In the opinion of the PBS legal staff, the Woody Allen show “presents fairness problems … personal attack, equal time and taste problems,” a solid guarantee that no public station in the country would risk airing it. Except, of course, our own WNET.

What I and a brace of our attorneys screened with nervous interest was a mock documentary, Men of Crisis, that mimicked the style of the old March of Time, in which authentic news footage was combined with dramatic elements, a technique Allen later perfected in his feature film Zelig. The original hour-long script had been trimmed to the twenty-five-minute “documentary,” and the balance of the hour had been filled by an interview with Allen on the nature of comedy. Men of Crisis managed not only to lampoon the Nixon White House but to needle both the president’s foes (Humphrey and Wallace) as well as his friends (Agnew, Hoover, Laird, and Mitchell). Allen himself played the fictional Harvey Wallinger, high-living confidant and counselor to the president, whose resemblance to National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger was more than coincidental. As might be expected, the show included moments of questionable taste. Allen explained that “it is hard to do anything about the Administration that wouldn’t be in bad taste.”

I withdrew the show after the screening, hoping to find a broader context to make Men of Crisis acceptable to the system, perhaps by marrying it with other satiricial pieces that took aim with prudent impartiality at a broader range of political icons.