In the final moments of a documentary on Francis Bacon, made by a French TV channel, the great artist turned to camera and jovially announced, in his best Franglais, that he had lost all his teeth to his lovers. That is what he was like –dramatically revealing intimate scenes from his life at the most unexpected of moments. His paintings did the same, as they were images, which unnervingly presented the “brutality of fact,” within the most intimate and commonplace of locations – a bedroom, a living room, a toilet.

I once played Francis Bacon on his deathbed, tended by nuns. It was for a drama-documentary, which examined the Bacon’s work through his asthma. The idea was to find out how much this medical condition shaped the artist’s life. For as Bacon once said to critic John Russell:

“If I hadn’t been an asthmatic, I might never have gone on painting at all.”

If this was true, then arguably, it was his asthma that made him a painter, and his asthma, which induced the heart attack that killed him.

Of course, there have been other suggestions as to why Bacon became an artist: the childhood trauma of being locked in a cupboard by the family nanny, or more luridly, as writer John Richardson has claimed, it was Bacon’s masochism that inspired his work. Yet, neither of these fully explain his drive or resilience, or the influence of his strange relationship with his father had on his work.

Bacon was 82-years-old when he died in Madrid, on the 28th April 1992. In many respects, it is a surprise he lived so long. Bacon was a prodigious drinker, had a damaged and diseased heart, lost a kidney to cancer, and once, nearly lost an eye, after being “pissed as a fart” and falling down the stairs of his favored drinking den. But Bacon had resilience, rather than seek immediate medical attention he merely pushed the offending orb back into its socket, and continued with his afternoon debauch.

Bacon was a gambler. He saw himself as open to the opportunities of chance in both his life and his art. He made and lost small fortunes on the spin of the roulette wheel. He was an atheist who saw no hope of an afterlife, and gave credence to “the individual’s perceived reality.” He claimed he had been “made aware of what is called the possibility of danger at a very young age,” which led him to treat life as if it were always within the shadow of death:

“If you really love life, you’re walking in the shadow of death all the time…Death is the shadow of life, and the more one is obsessed with life the more one is obsessed with death. I’m greedy for life and I’m greedy as an artist.”

In the late 1940s, Bacon was told by his doctor he had an enlarged heart. One of his friends, Lady Caroline Blackwood, then wife to artist Lucian Freud, later recounted a tale of a dinner when Francis had joined her and Lucian, at Wheeler’s Restaurant :

“His (Francis) doctor had told him that his heart was in such a bad state that not a ventricle was functioning; he had rarely seen such a diseased organ, and he warned Francis that if he had one more drink or even became excited it could kill him.

“Having told us the bad news he waved to the waiter and ordered a bottle of champagne, and once it was finished ordered several more. He was ebullient throughout the evening but, Lucian and I went home feeling very depressed. He seemed doomed. We were convinced he was going to die, aged forty.”

Francis Bacon was born, of English parentage, on the 28th October 1909 in Dublin. Bacon later said he had few happy memories of his “traumatically painful childhood.” His father, Edward Mortimer Bacon, an ex-army captain, was according to Francis, “a failed horse trainer.’” He was a tyrant and a sadistic bully, known and feared for his wild outbursts of rage. He also had a Victorian moralizing attitude, which terrified the young Francis. Unlike his two other brothers and his two sisters, the young Francis soon realized he was never going to be the son his parents wanted.

Lady Caroline Blackwood claimed the subject of his Irish childhood made Bacon “freeze”:

“He became agitated whenever I broached it. He started to tug at the collar of his shirt as if he were trying to loosen some kind of noose which he found asphyxiating; for a moment he resembled the agonized figures in his paintings, whose faces turn a truly dangerous shade of indigo-purple.”

Because of his asthma, the young Francis was considered the “sickly child of the Bacon household.” Being the “weakling,” as Bacon later described himself, did nothing to win the affections of his macho father, who delighted in putting Francis “on a pony and sending him off to hunt at every opportunity.”

His father was well aware that any prolonged contact with horses or dogs caused Francis to suffer an asthma attack, which left the child bed-ridden, “blue in the face, desperately struggling for each breath.” It is ironic the “weakling” Francis was the only one of the three sons to live beyond the age of thirty. One brother died after an asthma attack; the other, according to Bacon “a hypochondriac,” died from tetanus after cutting his finger while peeling potatoes.

In his superlative biography Francis Bacon: Anatomy of an Enigma, Michael Peppiat notes what is so exceptional about Bacon’s childhood, is that we tend to see it through his eyes - in his occasional references to it, and above all through his painting. Bacon’s artistic temperament was fuelled by a need for high drama and extremity to feed his painting, and it colored everything that came into reach.

At one point or another, in his various interviews, Bacon referred to specific incidents of cruelty that impressed themselves on his mind. As Peppiatt explains, one of the most disturbing stories, primarily because Bacon was so specific about it, and because he suffered it personally, is the story of his father arranging for his small son to be regularly horse-whipped by the grooms and stable boys - a punishment which reflected the father’s misguided attempt to make a man of his sickly child.

Bacon was to have his revenge on his father when he seduced his father’s grooms. The grooms were a source of sexual excitement and fixation for the Francis.

From as far back as I can remember I used to trail after the grooms at home.’

That these grooms, with whom Bacon had his first sex were the same ones that horse-whipped him is a tempting conjecture in light of Bacon’s adult sado-masochism and the tangibly violent sexuality that suffuses so much of his paintings. Michael Peppiatt also notes Bacon was sexually attracted to his father, who “ordered and witnessed the floggings, carried out by the grooms, who were themselves a source of sexual excitement, then the complexity of emotions is more than sufficient to make any later violence, in life and in his art, almost too easy to explain.”

Bacon described himself as “completely homosexual”, and his father’s exasperation at Francis’s sexual orientation reached breaking point when he discovered the precocious boy dressing up in his mother’s clothes:

“One day my father caught me trying on some of my mother’s underwear. I must have been 15 or 16 at the time. He threw me out of the house.”

After being thrown out of his parental home, his mother organized a small monthly income, and his father had him shipped off to a tough military uncle, who promised to put some sense in the boy. The uncle took the impressionable Bacon to Berlin then Paris. The seemingly strict and austere tutelage offered by the uncle did not last long, as within two days of their arrival in Berlin, the uncle and nephew were in bed with each other.

If anything, this experience allowed Bacon to revel in his sexuality and to have his first taste of the Bohemian and artistic worlds that were so anathema to his father. The uncle would be the first of many older lovers who would help the young Francis with his artistic and social education.

It was during this first trip to Paris, in 1928, that Bacon saw the Picasso retrospective, which inspired Francis to become an artist. It was also in Paris, after his uncle had abandoned him for another young man, that Bacon had his first experiences as a male prostitute.

While sex proved liberating, it was, as Peppiatt notes, Bacon’s lifelong asthma, which was perhaps the most important key to understanding his childhood and his adult sensibilities that came from it.

“For an asthmatic, the simple process of breathing is a struggle, each attack is an ordeal to be overcome, and during Bacon’s childhood little existed to alleviate the protracted suffering.

“Nevertheless, asthmatics generally acknowledge that their condition sharpens the will to live, making mere existence - what Bacon called ’conscious life’ - a pleasure itself, since it has been so arduous to achieve.

“The asthmatic tends as a result to have a special fund of optimism, simply in order to surmount a new attack; and once the attack has passed, the optimism does in deed seem justified. Bacon himself referred all the time to his ‘optimistic nervous system’ (while qualifying it atheistically as ‘optimism about nothing’ ), and this can be understood more fully in the context of his permanent struggle with asthma.

“If this early ordeal gives the asthmatic unusual resilience and reserves of stoicism, it also tends to form a character that appears aloof to the daily miseries of living. A certain unfeeling superiority or ruthlessness characterized much of Bacon’s behavior in later life, to the extent that many people who came into contact with him failed to see the instinctive compassion and the sometimes startling generosity with which he responded to those whom he liked or in some way felt responsible for.”

Asthma was a hereditary ailment within the family, and in later life Bacon frequently toyed with the idea of living for part of the year in a dry climate, like his maternal grandfather, John Loxley Firth, who had tried to relieve his asthma by spending the worst of the winter in Egypt (a fact the grandson remembered because the location sounded so alluring).

Years later, after his father died and his mother remarried and settled in South Africa, Bacon seriously considered moving there to help ease the worst attacks of his asthma. Oftentimes during the damp, wet winter months in London, Bacon found himself struggling to breathe as he painted in his cold, cramped studio. With this in mind, Bacon’s paintings take on a different meaning, the blue faces gasping not screaming, their bodies convulsed in severe asthmatic spasms.

His affliction proved useful when Bacon was called-up for National Service during the Second World War. Francis hired a dog from Harrods and spent two days and nights lying and sleeping with the long haired mutt. When he presented himself at the call-up board, Bacon’s dire allergic reaction to the dog was more than apparent - his face was purple, his eyes were streaming, he was virtually unable to breathe. Bacon was excluded from service. However, he did volunteer for the ARP (Air Raid Precautions).

For Bacon, with his private sense of suffering and his imagination nourished by Greek tragedy, the scenes of death and destruction probably only confirmed an underlying belief in man’s inhumanity to man. Like everyone else who lived through the bombings, however, he was nevertheless deeply marked by the war. “We all need to be aware,” he later said, “of the potential disaster that stalks us everyday.’ Worsening asthma aggravated by the clouds of fine dust obliged Bacon to give up even his involvement in the war, though one must remember that, because of his medical discharge, he was not obliged to serve in any capacity at all.

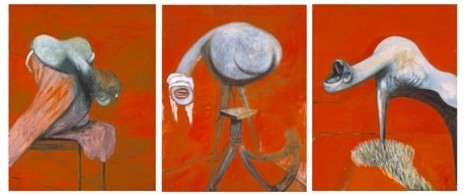

The war gave Bacon time to develop his artistic vision, which culminated in Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944).

Inspired by The Eumenides from Aeschylus’ The Oresteia, in particular the phrase “the reek of human blood smiles out at me,” as he explained to the French art critic Michel Leiris:

“I could not paint Agamemnon, Clytemnestra or Cassandra, as that would have been merely another kind of historical painting…Therefore I tried to create an image of the effect it produced inside me.”

It was a revolutionary and sensational painting, which announced Bacon as the foremost artist of his generation. Critics and patrons were unnerved by the work, The critic John Russell said he was shocked by:

“images so unrelievedly awful that the mind shut with a snap at the sight of them. Their anatomy was half-human, half-animal, and they were confined in a low-ceilinged, windowless and oddly proportioned space. They could bite, probe, and suck, and they had very long eel-like necks, but their functioning in other respects was mysterious. Ears and mouths they had, but two at least of them were sightless.”

At the time, Bacon lived a ramshackle life with his childhood nanny, Jessie Lightfoot, in a cramped London flat. The flat was so small, Lightfoot slept on the kitchen table. Together they ran an illegal gambling den, where Jessie vetted all potential suitors for the young artist, including the ‘gentlemen’ who applied to employ Bacon as ‘a gentlemen’s gentleman’.

Though unknown as an artist, Bacon was a recognizable figure around the Earl’s Court and Soho areas of London. His appearance was heavily made up with thick make-up, lipstick, and a strange combination of brown boot polish to darken his hair, and toilet scouring powder to whiten his teeth. He had also attracted the interest of a variety of policemen, after making public his penchant for wearing fishnet stockings, suspenders and women’s knickers under his trousers. As he would later recall, “The blackouts were a most wonderful time.”

Bacon had no formal training as an artist. Like his school education, he was self-taught and strongly influenced by some of his early lovers, Eric Hall and in particular Roy de Maistre.

Bacon’s paintings show a constant interest with the mouth and the internal dysfunction of the body. His subjects squirm, convulse, as if they had no control of their bodies. Bacon claimed that he was trying to find out a truth about the figures he painted, and admitted that he had to know a model well before he could inflict “such violence on them.’”

His paintings also merged elements from his life. For example, in Figure Study II(1945-46), shows a man bent over and half-naked, a coat is draped over the lower part of his back. The positioning of the body suggests both an act of sex, or the memory of Bacon being horse-whipped. What makes the painting more disturbing is the blind scream or gasp that emanates from the figure’s mouth, as if desperately trying to breathe.

The repeated use of the enclosed space, or ‘glass box’, as evident in the series of Popes (1951-65) or Heads’ (1949), also present the viewer with nightmarish images of suffocation.

Bacon cross-referenced his paintings with differing source material, from medical text books to Muybridge’s photographs. His portraits of Lucian Freud were taken from a picture of Franz Kafka that “suggested” something of the “look” of Freud.

As in the series of Popes, the portrait of Innocent’s face is not so much derived from Velazquez’s painting, but rather lifted from a photograph of Bacon’s father.

The image is made more complex as Bacon cross-referenced Velazquez with his own father and the iconic image of the shot nurse from Eisenstein’s Battleship Potempkin, which was one of Bacon’s favorite films. This he added to by making it a portrait of Jessie Lightfoot.

This cross referencing makes Bacon’s paintings all the more shocking, once the images are unraveled and their associations contextualized with the events of Bacon’s life.

Moreover, Bacon’s father haunts much of Francis’s work.The only time that Bacon claimed he had seen his father openly show emotion towards another human being, was on the death of his younger brother, Edward’s favorite son. Bacon’s brother allegedly died from an attack of asthma. It is with a bitter irony, and obvious personal pain, that Edward horse-whipped Francis for his asthma, and cried when his other son died from it. Peppiatt claims the image of the Pope reveals much more than just Bacon’s anger to his father, but also his “painful sexual betrayal.”

When once asked by the critic and writer, David Sylvester, whether the paintings of the Popes was in anyway influenced by his father (the words, as Sylvester pointed out, il papa meaning the father’), Bacon coyly but revealingly answered :

“I don’t know - it’s difficult to know what forms obsessions. The thing is I never got on with either my mother or father.”

And :

“Well, my relationship with my father and mother was never good. We never got on. They were horrified at the thought that I might want to be an artist. They said, well, you will never earn your living as an artist, there is no possible chance of it, so they were totally against it. I can’t say I had a happy home life. I had two brothers and two sisters, one of my brothers went out to Rhodesia, somehow he got tetanus and died. And my younger brother died very early on. I remember the only time that I saw my father show any emotion was when my younger brother died; he was really very fond of my younger brother. But I had no real relationship at all with my father. He didn’t like me and he didn’t like the idea I was going to be an artist. You see, there was no tradition of that kind in the family at all, and they thought it was just an eccentricity in a son of theirs to think he would like to be an artist.”

Originally posted on 01/29/11.