Scene: A suite at the St. Regis Hotel, New York City, 1938. The floor is knee-deep in coils of highly flammable nitrate film. It sprawls across the floor, hangs from light fittings, bedposts, armchairs, tables, and glistens like a pit of malevolent serpents.

Center of the room stands boy wonder, Orson Welles, fueled by coffee and brandy and chicken sandwiches. He stands, puffing on an oversized pipe, filling the room with big black cartoon clouds of train engine smoke punctuated with angry fireflies of tobacco sparks which threaten (at any moment) to set the whole place alight. Welles is intently staring at one roll of film he slides up and down between his hands. He is oblivious to the chaos and possible fatal disaster that surrounds him.

His assistant John Berry is wrestling with a movie projector on which a roll of film has become snagged and is now kindling to a burst of yellow flames. Berry carries the projector back-and-forth anxiously looking for a safe place to dump the now smoking machinery. In front of him, like the best stage farce, a selection of doors offer escape but all are closed shut.

At one, there is a-knocking of someone wanting to get in. The door opens hesitantly. It’s producer John Houseman who has come to see what’s going on with the latest project Too Much Johnson. Houseman enters, retreats, enters, retreats, as if shyly rehearsing dance steps. He eventually opens the door wide, coughs once, then enters the room. He opens his mouth to speak but the shock of seeing 25,000 feet of highly flammable film decorating the floor, Berry with a burning projector seeking escape, and an oblivious Welles smoking like a volcano is all too much for him. He attempts to retreat back to the hallway while comically elbowing Berry over who gets out first.

Exit Houseman and Berry with flaming projector.

This is roughly around the moment when Orson Welles fell in love with movie-making and decided making movies was to be his future career.

Orson Welles making magic out of thin air.

Welles and Houseman were the bright young bucks of NY theater. Their innovative, critically acclaimed, and highly successful productions of an all-black Macbeth in 1936, followed by Marc Blitzstein‘s socialist musical The Cradle Will Rock, led Welles and Houseman to form their own repertory company the Mercury Theatre in 1937. Their first production as the Mercury Theatre was a jack-booted, militaristic production of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar called Caesar. It earned the pair column inches of praise and reputations as a major force in American theater.

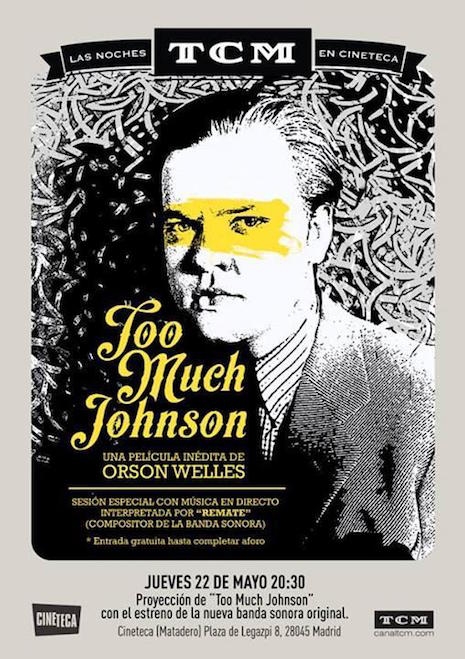

In 1938 came productions of The Shoemaker’s Holiday and George Bernard Shaw’s Heartbreak House. Both of these received five-star reviews for their direction, acting, and original and creative approach to theater. Welles was always thinking up new and fresh ways to present well-known dramas. The Mercury’s next production was to be William Gillette‘s farce, about the misadventures of an amorous young man, Too Much Johnson which was more Welles’ baby than the “scholarly” Houseman’s, who was left to raise the cash and carry props. Gillette was the American actor who was famous for his character-defining performance of Sherlock Holmes—an interpretation that gave Arthur Conan-Doyle’s fictional hero many of the accessories, mannerisms, and tics still associated today with the renowned Baker Street sleuth.

Thinking of how to make Too Much Johnson seem new and original for the audience, Welles decided on filming a twenty-minute introduction to the play, with two ten minute sequences to be screened before acts two and three. There was no money to shoot these inserts, so Welles begged and borrowed and cajoled Houseman to raise whatever cash he could find. Too Much Johnson was to open at the Stony Creek Theatre in Connecticut. Welles was going to use the stage actors to perform in the inserts but gave so much of his time over to working on his filmed inserts, he left himself little time to focus on directing the actors for the stage production. Not that Welles was bothered—he was keen on improvising parts of the stage show.

Filming started in July 1938 amid all of Welles other commitments to radio, writing, and directing other productions. Welles decided on making his short film a homage to the zany Mack Sennett comedies of the silent era. He asked Paul Bowles to write the music for these inserts, who in turn suggested to Welles he hire cameraman Harry Dunham.

Dunham came from a rich background, had graduated from Princeton then bummed around Morocco and Paris, where he got to know and hang-out with the likes of Andre Gide, Gertrude Stein, and Man Ray. He was, at one point, Stein’s “dog-washer.” Dunham had also shot his own documentary film about Mao-Tse Tung and the Red Army in 1936. He was a Communist and later made short campaign films for the Communist Party. Dunham understood exactly what Welles wanted to achieve, and the pair collaborated on making a startlingly original homage to the old silent two-reelers.

For his cast, Welles called on the actors from the repertory of Mercury players like Joseph Cotton, Mary Wickes (who later provided the live-action model for Cruella De Vil in Disney’s One Hundred and One Dalmatians), Edgar Barrier, Arlene Francis (who later became a regular on the panel show What’s My Line?), the model and actress Ruth Ford (sister of Charles Henri Ford), and vaudevillian Howard Smith, with Welles, Houseman, Berry, and Blitzstein playing extras.

Joseph Cotton and Edgar Barrier.

Three years before Citizen Kane, Too Much Johnson was Welles very first time directing behind a camera. With no money and no studio in which to work, Welles used his considerable imagination to make his ideas work. He used Central Park, Battery Park, and various sites in New York, with anyone not in front of the camera being asked to hold up the flimsy film sets. It was exhausting work. The crew was expected to work long days with few breaks and virtually no pay. On one occasion, when some of the crew broke to eat food after around sixteen hours of holding up the sets, Welles demanded what the hell did they think they were doing? His assistant Berry, who was one of the wall-holders, explained they had not eaten. Welles made a great show of organizing food for the crew, offering his director’s chair to Berry, so he could sit and eat. As Berry later recounted, this was Welles manipulating his crew to get what he wanted. Once sated, the crew reluctantly went back to holding up the sets.

During filming, Welles had to deal with the NYPD chasing the production off various locations as he had failed to organize a filming permit. He also had legal rumblings from Hollywood as one studio had the film rights to the play and considered Welles’ inserts copyright infringement. As the film sequences grew, Welles became more and more preoccupied with filmmaking rather than the stage production. He ran out of money and had to battle with the labs to have his footage processed. It was almost a premonition of what was to come for Welles’ movie career. But through all this, Welles had not factored in one key thing—it was not possible to screen the footage at the Albany Theater as there were no projection facilities.

The play eventually opened to mixed reviews with critics and audience alike left confused by the lack of connecting storylines which were filmed but never screened. Too Much Johnson was long thought lost but turned up among Welles personal belongings at his home in Spain in 1970. However, a fire at this home destroyed the print. All was thought lost until a second print of the film was discovered in Italy in 2008. A long process of restoration then followed which left a total of almost an hour of rushes from with the following is but one cut.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

‘Touch of Evil’: The movie that finished Orson Welles in Hollywood

Orson Welles hated Woody Allen

F is for Orson Welles’ FBI file