From the late 1930s until the early 1970s, a sprawling 32-acre spread in northeast Ohio known as Hines Farm, with its own open-air juke joint and enclosed night club, regularly attracted thousands of African-Americans with its ass-kicking blues parties. Hines Farm must have been a really special place, an oasis of incredible blues music, southern food, and (by the way) racial tolerance. It offered good times for all, with a roster of entertainments you wouldn’t find in New York City quite so quickly: roller skating, amusement park rides, exhibition baseball games, horse races, hobo car races, motorcycle races, squirrel hunts…. the list goes on and on.

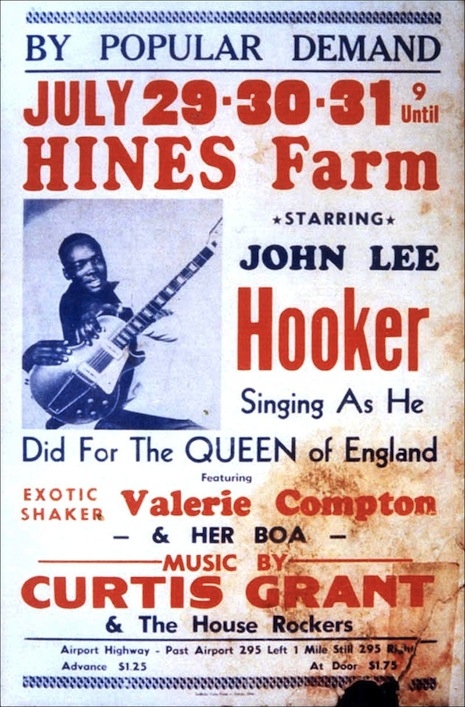

Some of the biggest names in blues played there—B.B. King, Bobby Blue Bland, and John Lee Hooker, as well as jazz figures like Louis Jordan and Count Basie. Basie and his full orchestra were hired to play the grand opening of an outdoor pavilion in 1961. The pavilion doubled as a roller rink and a dance floor and could accommodate 1,500 people. People would come from miles around, from as far as Detroit or Cleveland, for the rollicking fun on summer weekends.

When B.B. King thinks of Hines Farm, he recalls the “good food, good music, and pretty girls. It was the only place that was happening.” John Lee Hooker called Hines Farm “a one and only place—wasn’t no other place like that I have been to that was like Hines Farm.” Hines Farm’s identity as an informal place for African-Americans to unwind, relax, and enjoy life started in the basement of Frank and Sarah Hines in the 1930s. By the late 1940s they had the first liquor license held by an African-American in northwest Ohio, and by 1957 they constructed an actual blues club.

Blind Bobby Smith, a Toledo blues guitarist who did session work for Stax Records, used to play in their basement in the early days. According to Smith, “After they’d close down outdoors we’d all pile in the basement. In the wintertime [Frank Hines] just ran it out of the house. It was, you know, everybody talkin’ at the same time ... passing the bottle around, and Hines wishin’ everybody’d get out of there so he could go to bed.”

Sarah and Frank Hines

For African-American men, Hines Farm was a place for sex, a place to dance and meet women. A neighbor recalled wistfully, “Man, it was good to go back there in the woods. See, I never took my car. I’d just walk back there and have me a cold beer and watch ‘em dance. See, that place back there, they used to dance. Chicks would come out of Toledo. Some of them ol’ gals was good lookin’. I’d sit there and drink beer and watch ‘em from mid-afternoon. Hell, I wouldn’t leave ‘til dark ... watchin’ them chicks shake it up.”

According to Big Jack Reynolds, one of the regular performers in the club’s early days, Mexicans and whites were perfectly welcome as well: “There was no discrimination there.” As Marlene Harris-Taylor, who has co-produced a documentary about Hines Farm, said, “When most African-Americans came north, they moved into urban areas. Most of the jazz and blues clubs that sprang up were in the urban settings. Hines Farm was unique. It was like home for African-Americans who had moved here from the rural South.”

The interior of Hines Farm Blues Club

It was Frank Hines’ job to keep the peace. Hines would check everybody for knives and guns and just take them, then return them when they left. Frank’s wife Sarah was the same way, wouldn’t let any trouble start. Henry Griffin, who owned the property of Hines Farm after the blues club was discontinued in 1976, remembered, “One time Sarah broke a beer over a guy’s head. He got out there and played like he was drunk and was sayin’ a lot of filthy talk in front of the women, and she tried to get him to hush, you know, and he wouldn’t do it. So she went to him a couple of times. The third time, he started all kinds of that filthy talk, and she just took a beer bottle and went up there and hit that son-of-a-bitch on top of his head. That damned bottle shattered all to pieces, man, and that guy said, ‘She tried to kill me.’ He grabbed his head and said, ‘She killed me. I’m gonna tell Sonny’—that’s what everybody called Frank Hines. She said, ‘I don’t give a damn if you tell Sonny—just get the hell out of here.’ And it was peaceful the rest of the night.”

It also had motorcycle races, which were a really big deal. It’s the one thing that everyone who was there recalled, aside from the food and music. Griffin remembered: “Hines would send out a flyer that he was havin’ a motorcycle race and he would have people come from Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and they’d get on their motorcycles and ride right up there. And there’d be thousands of ‘em.”

Hines Farm shut down in autumn 1976 and quickly fell into disrepair. Steve Coleman, son of Griffin, who passed away in January 2013, has the place up and running again.

In this documentary clip, B.B. King and John Lee Hooker reminisce about Hines Farm:

Thank you Charles!

Sources for this post include “Historical Blues Club to Reopen” and “Remembering Toledo’s Blues Showcase,” both from the Toledo Blade, and this expansive piece from Toledo’s Attic by Thomas E. Barden and Matthew Donahue. Matthew Donahue is the author of I’ll Take You There: An Oral and Photographic History of the Hines Farm Blues Club. Buy it!