In early February, I attended a weekend of rare Seijun Suzuki films at the American Cinematheque here in Los Angeles. Although big screen showings of his work are happening more frequently and Arrow Films is putting many of his films out on disc, when these mind-melting cinematic explosions come around they ALWAYS fall into the “cancel everything else you had planned and get tickets for every show” category for me. This particular retrospective was almost all 35mm, early work and many were flown in especially from Japan. There was no way I was skipping it.

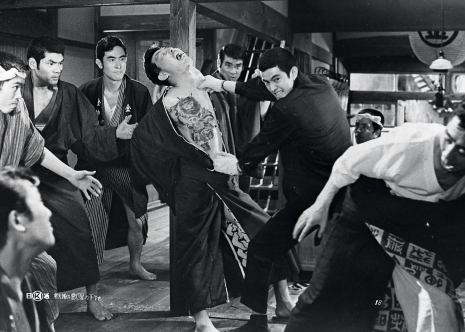

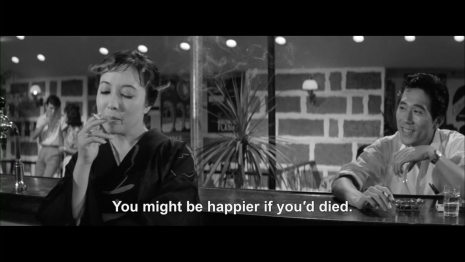

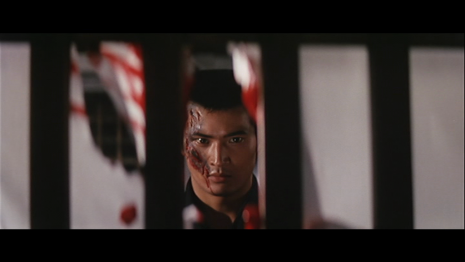

A few films were the most stunning prints I have seen in ages. The theatrical experience of Suzuki’s first color film Fighting Delinquents (1960, also titled Go to Hell, Punks!) was better than any date I’ve had in ten years. Provided by the Japan Foundation Film Library, this 35mm print was in excellent condition; its color exceptionally deep and rich. The film preservationist in me was going apeshit while the film fan was swooning like a teenager at a Beatles’ show. Shot in Cinemascope, Delinquents filled the screen, allowing Suzuki to exploit every goddamn inch. Seijun Suzuki’s cinema should be experienced in a theatrical space if possible. His female characters are tough and nuanced, his Yakuza guys are bizarre but kickass, and the music is always amazing. Seijun Suzuki makes a lot of films that seem like fever dream surrealism (he’s known for being “crazy”) but I experience them as wild and exciting takes on traditional genre work. He makes THE BEST juvenile delinquent, crime and Westerns movies. He just synthesizes them through Japanese and his own patented “Seijun Suzuki-ness.”

I am grateful that my friend and colleague, Will Morris, a programmer at the American Cinematheque who planned and executed this magical series in tandem with another wonderful Will—Will Carroll. Carroll made the magic of this Suzuki Retrospective happen in the first place and is a fascinating human! I spoke briefly with him about how these prints came to the US in the first place, picking his Suzuki-riddled brain. Will is currently a PhD candidate in Cinema and Media Studies at the University of Chicago. His dissertation, Suzuki Seijun and the Redemption of Cinephilia, deals with Suzuki Seijun and the fallout from his firing by Nikkatsu Studios in 1968, focusing particularly on the ways in which his films were subsequently championed, or perhaps commandeered, by various groups of film theorists. Sounds awesome, right???

Dangerous Minds: Thanks so much for organizing such an amazing retrospective of rare works. Can you give a short account of how this process occurred?

Will Carroll: A few years ago, Tom Vick released his book on Suzuki and put together a traveling retrospective. I ended up going to New York and Boston to see some of the films that weren’t playing in Chicago (we had a very abridged version of the series: the only rare films that screened here were Carmen from Kawachi and Clandestine Zero-Line) and I decided to put together an event on campus to bring another one of the rare films to us. I contacted Tom Vick (whom I had never met before) and he very generously put me in touch with Japan Foundation and helped me put the event together, and came out to do a Q&A for it. After that, I made inquiries with Japan Foundation about what other rare Suzuki films they had in subtitled prints. For the series, I just picked all of the rarest films that they had: either films that didn’t screen as part of the traveling retrospective in North America a few years ago, or really good ones that had played in other places but not Chicago and weren’t widely available (notably Eight Hours of Terror, A Tale of Sorrow and Sadness, and Capone Cries in His Sleep).

Why is it so difficult to see Seijun Suzuki films? What would you say the most difficult one(s) are to see?

Suzuki gained the attention of student cinephile circles in Japan starting around Gate of Flesh (Nikutai no mon) in 1964. There had been a little bit of interest in him before then (Kanto Wanderer got a single vote for Kinema Junpō‘s ten best list in 1963), but it was really after that film that interest took off, and newly emerging student film groups like Tokyo Cine-club began hosting retrospectives of his films in the mid-1960s, but with the emphasis always being on the later Nikkatsu films…The interest in Suzuki really took off when he was fired by Nikkatsu and Cine-club tried to hold a complete retrospective of his work, but Nikkatsu blocked the release of his prints. It led to large student demonstrations, and the involvement of filmmakers like Ōshima Nagisa, Matsumoto Toshio, and other new left filmmaking figures. The event was somewhat analogous to “the Langlois Affair” in France the same year (which wasn’t lost on observers in Japan—in 1968, film journals like Eiga Hyōron had entire sections dedicated to “The Langlois Affair and the Suzuki Incident”). The irony was that at the point he became this famous, nobody could watch his films because Nikkatsu was blocking their circulation. I think this moment might have aroused interest in some of the earlier films, and some of the films that hadn’t gotten so much attention yet, but since no one could watch them, the emphasis in all the writings that came out about Suzuki at the time were on the films that his defenders already knew: Youth of the Beast, Kanto Wanderer, Gate of Flesh, Tokyo Drifter, Fighting Elegy, and Branded to Kill. He didn’t become known in the West particularly until the Taisho films traveled on the festival circuit in the 1980s, and eventually some of his Nikkatsu films began playing at retrospectives in Europe and North America, but again the emphasis was always on these same films.

The most difficult film of his to see is There is a Bird Within a Man (Otoko no naka ni wa tori ga iru), a television project he made in 1969 that was completed but never released…There are a few films of his available on DVD in Japan that haven’t been released in the U.S. or the U.K., though some of them in limited pressings: Harbor Toast: Victory is Ours, The Age of Nudity, Carmen from Kawachi, Capone Cries in His Sleep, and a few others that are now coming out with the new Arrow box sets. In general, though, you have to rely on repertory screenings of the films either in Tokyo or on Nikkatsu’s movie channel (Neco) to see a lot of the earlier films.

So these new Arrow Films DVD/Blu-ray box sets—Seijun Suzuki: The Early Years. Vol. 1 Seijun Rising: The Youth Movies and Seijun Suzuki: The Early Years. Vol. 2. Border Crossings: The Crime and Action Movies —are being released very soon. As a Suzuki scholar, what are your thoughts?

The fact that Arrow has now released two Suzuki Blu-ray box-sets in the past year and are scheduled to release another one later this year is certainly promising. I actually ended up swapping around a few films that were in the series after they announced the first box-set…The one I kept in was Born Under Crossed Stars, because I think it’s too good…

The one film that’s part of the second upcoming set that has never been officially subtitled (as far as I’m aware) is Tokyo Knight (which is great fun, by the way). I’m glad that with these new box sets of the early work, we are starting to see some attention drawn to some of the earlier films that have thus far been largely written out of the Suzuki narrative. There are some really odd items among his early films, including quite a few that aren’t among the ones getting released. But there are also some films from his late Nikkatsu period that haven’t gotten as much attention that I’m hoping to see a wide release of at some point as well, notably The Call of Blood (a.k.a. Our Blood Will Not Forgive) from 1964 and Carmen from Kawachi from 1966, which are, to my mind, two of his best films. I guess all I can say for now is: I’m hopeful.

_465_198_int.jpg)

“Seijun Suzuki: The Chaos of Cool” via Criterion.

Seijun Suzuki interviewed at the NuArt Theatre in Los Angeles, 1997