Bones. This is what we come to once we’re dead and the soft tissue has gone. Bones. The sturdy architecture that shapes and protects our bodies. Most of us will end up as dust or ashes, or if very, very lucky, may one day become fossilized and exhibited in a museum as an example of a dumb 21st-century Homosapien. There’s nothing else once we’re dead. No seventy-two virgins (or is it dried fruit?), no Alleluia chorus, no wings and no harp, just the remnants of a structure that once held us together.

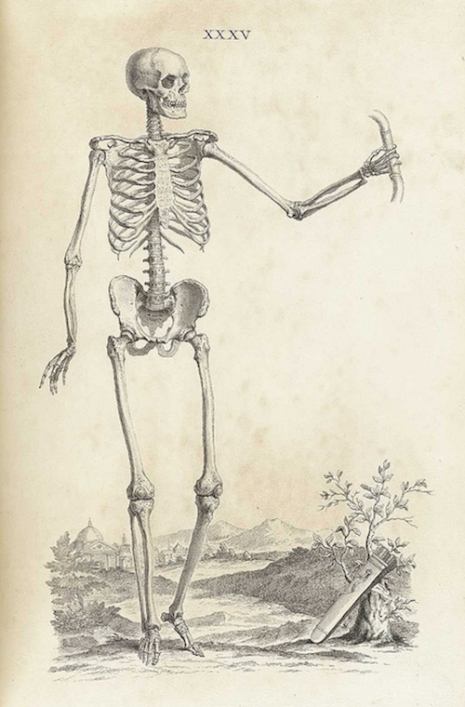

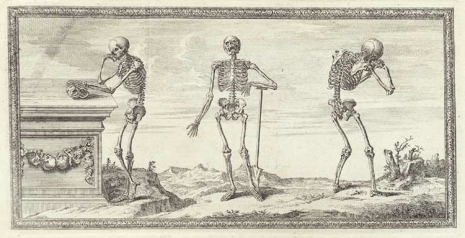

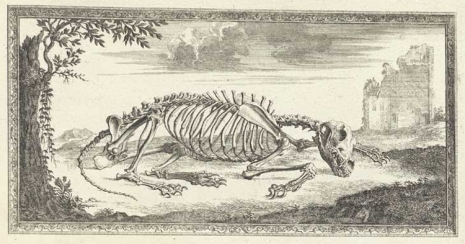

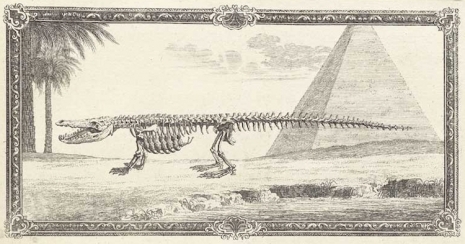

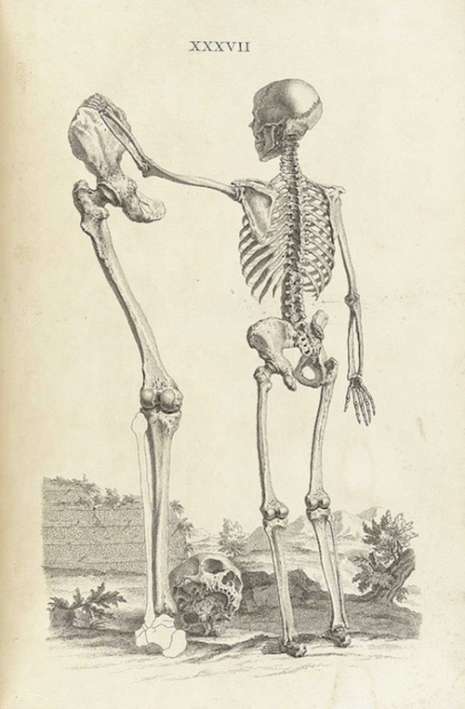

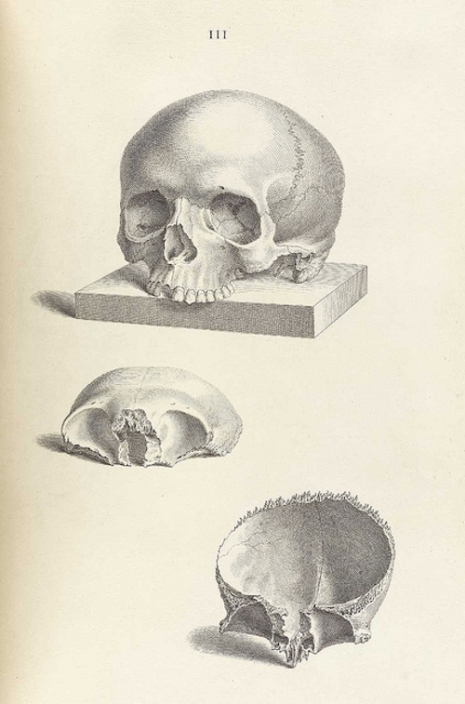

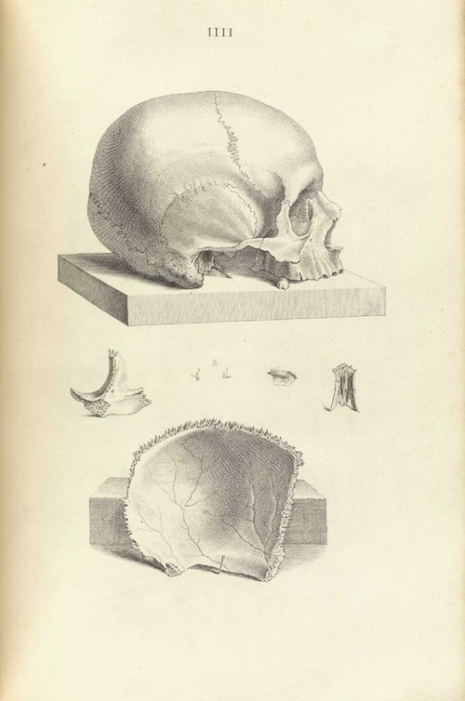

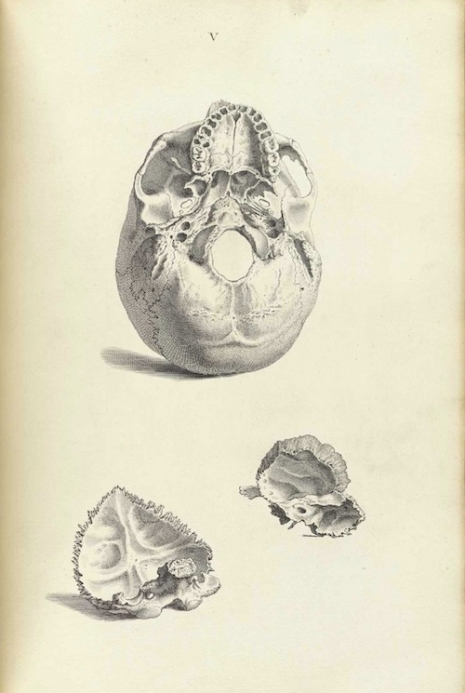

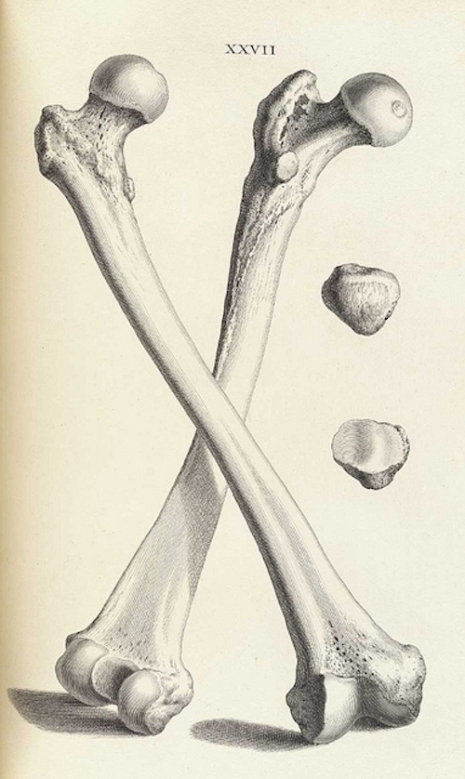

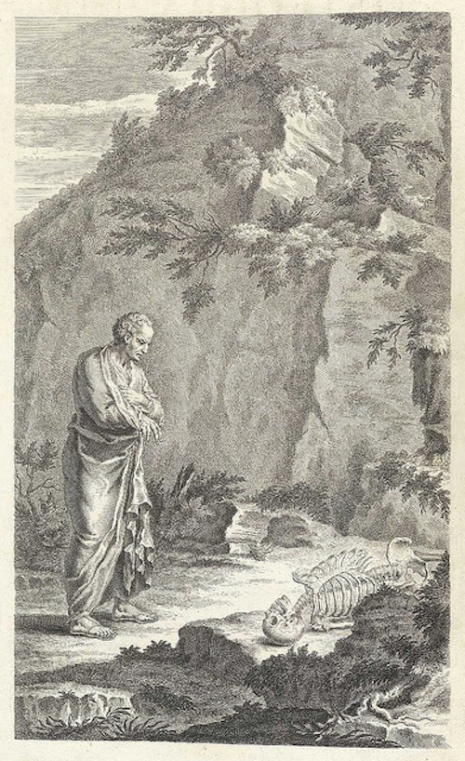

Humans are born with 270 bones which gradually fuse during childhood to become the 206 individual bones of adulthood. Bones are damned amazing things. They are tough, flexible, and protective. They are made of a composite of materials including collagen fibers and calcium phosphate. In 1733, William Cheselden (1688-1752) published his Osteographia or The Anatomy of Bones—a lavish and beautifully illustrated book of human and comparative osteology. It was the first fully accurate description of the human skeletal system. Cheselden was already renowned for his previous volume The Anatomy of the Human Body (1713) and now hoped to do for bones what he had done for the flesh.

Cheselden was a surgeon and teacher based in London. He was appointed surgeon at St Thomas’ Hospital in 1720 and then at St George’s Hospital in 1733. His specialty was in the removal of bladder stones, though he later became far better known for his work in eye surgery, especially the removal of cataracts. He was also surgeon to Queen Caroline. As a teacher, Cheselden wanted to share as much of his medical knowledge and experience as possible.

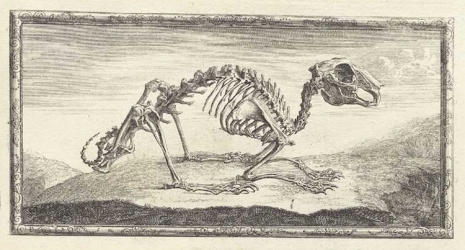

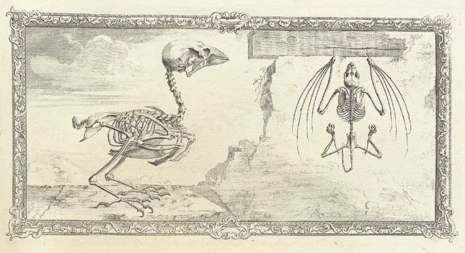

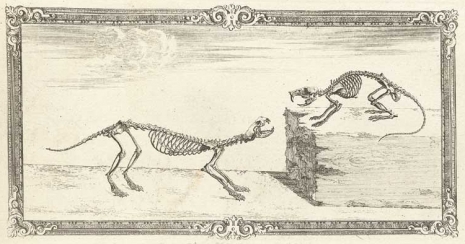

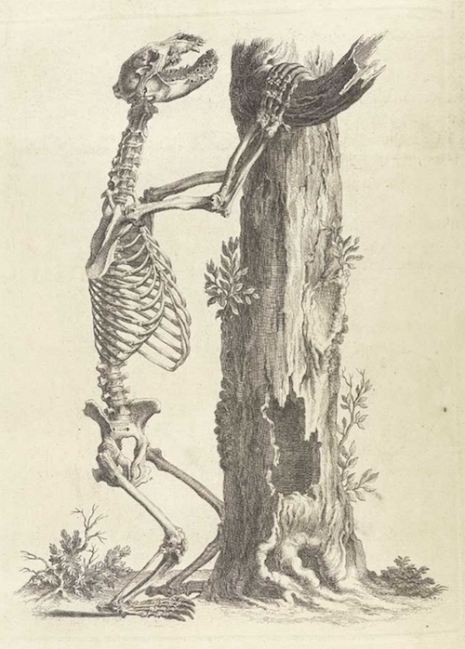

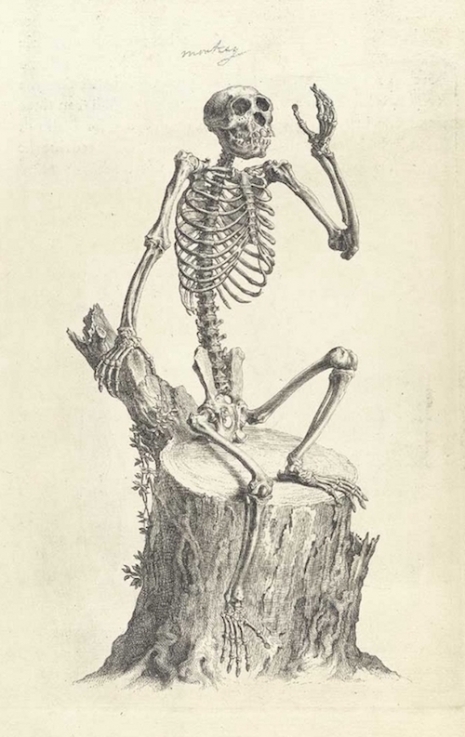

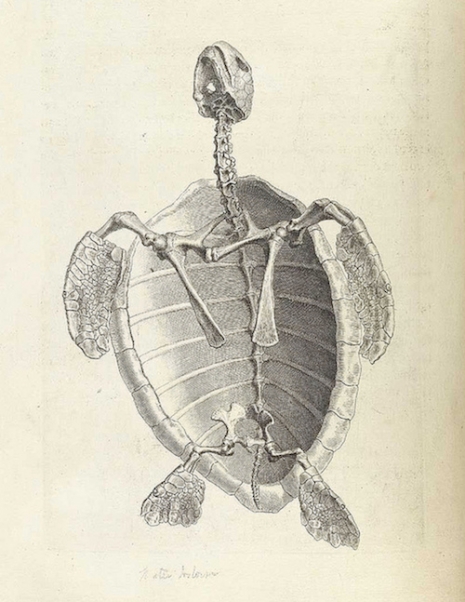

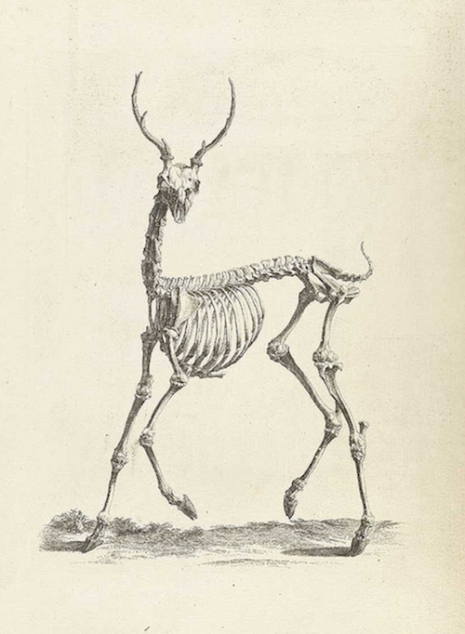

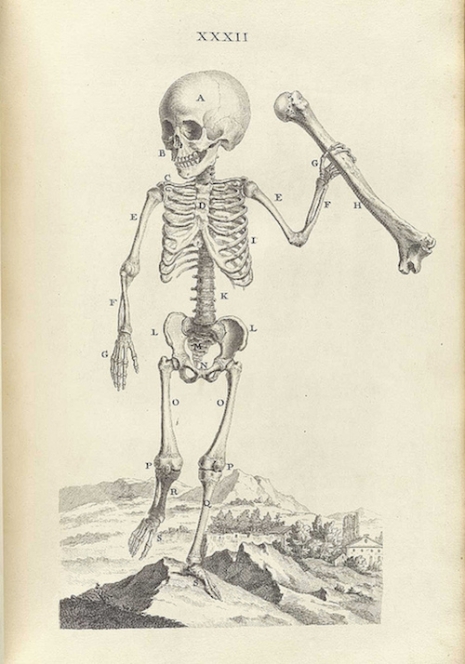

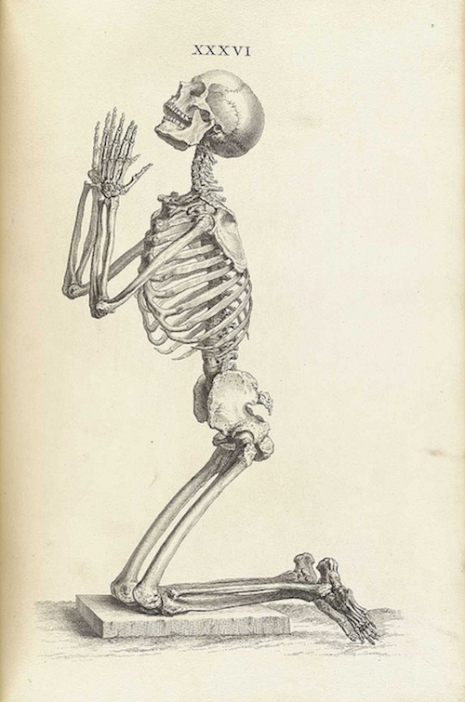

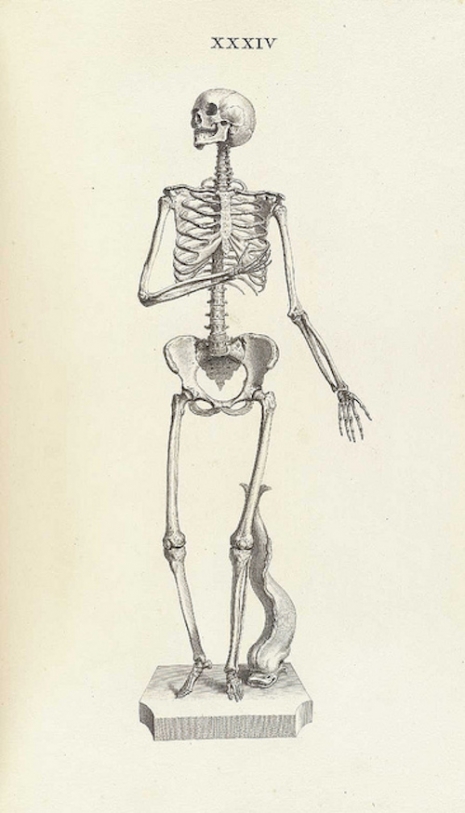

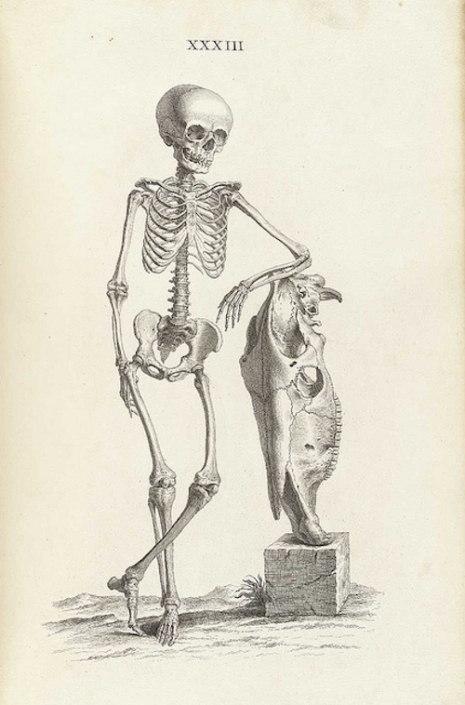

For the Osteographia, Cheselden employed two artists, Gerard Vandergucht and Jacob Schijnvoet, to illustrate the anatomy of bones. To ensure accuracy in the illustrations, Cheselden made use of a camera obscura which transposed the image of each bone onto paper for the artists to copy. However, many of the skeletons were presented in strange so-called realistic positions—for example the skeleton of a cat arching its back at the sight of an approaching dog, or a man kneeling down praying. This was achieved by wiring the skeletons into position, which more often than not detracted from any attempt at factual representation. Thus the book proved to be a failure, though today Cheselden’s Osteographia is considered one of the great historical works of art and science.

Those with an interest can view the whole book here.

Via Public Domain Review.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

Disturbingly beautiful (almost dirty) images of human anatomy from the 1700s (NSFW)

Jeepers Creepers: Surreal illustrations of witchcraft-caused eye diseases from the 16th century

Exterminate!: Anatomy of a Dalek