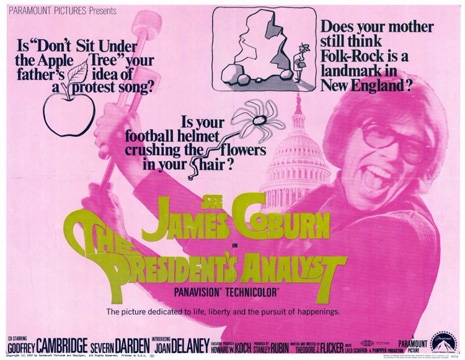

Twelve years ago I found myself at Cinefile Video in West Los Angeles when I happened to notice a movie poster on the wall for the 1967 film, The President’s Analyst. The duotone pink and green poster depicted James Coburn wearing a `60s mod wig and sunglasses holding two gong mallets in his hand with the tagline, “Is your football helmet crushing the flowers in your hair?” What the hell kind of movie is this? I had recently developed a fascination with James Coburn after discovering the sixties spy-spoof films Our Man Flint, and the sequel, In Like Flint. Perhaps it was due to exposure to late `90s pop culture references like the Beastie Boys album Hello Nasty or the movie Austin Powers (both of which named dropped the character Derek Flint) that Coburn had been embedded into my subconscious at that time.

I went home that night and watched The President’s Analyst. It was absolutely fantastic in the way it ridiculed virtually every important `60s institution—establishment and anti-establishment alike. But unlike most 1960s-era political satires and comedies, it was surprisingly fresh, relevant, and still laugh-out-loud funny in the present age. A man I had never heard of named Theodore J. Flicker was credited as the film’s writer and director. After repeated viewings I began to wonder: who is Theodore J. Flicker? How come nobody’s ever heard of him? How is it possible for someone to make a film this good and then vanish completely from sight? The lack of information available on the internet only fueled my interest, but I eventually learned that Mr. Flicker had been blacklisted from Hollywood. But why, how could that happen? I would end up going to great lengths to answer these questions, including a trip to Santa Fe, New Mexico to find Flicker, who spent the last twenty years of his life as a sculptor.

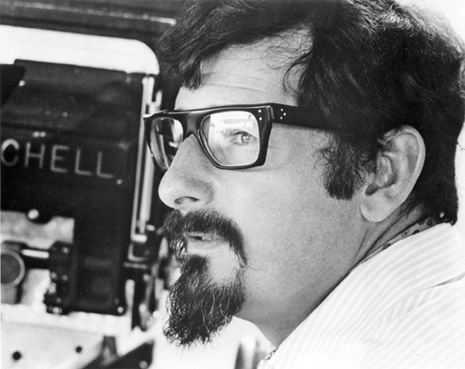

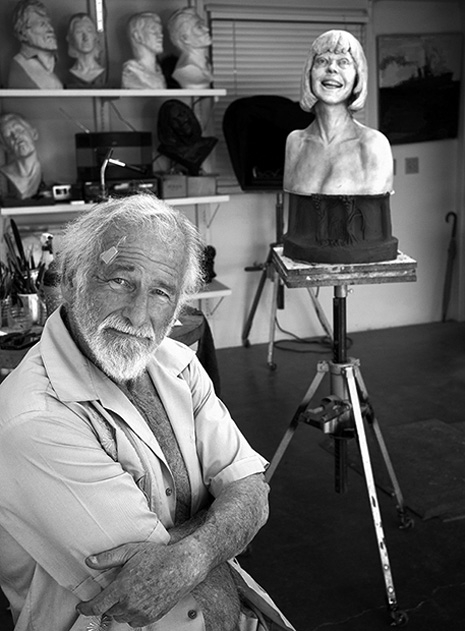

Ted Flicker in Santa Fe, Sept 2013. Photo by Doug Jones

After failing to open a theater of his own in New York City, Theodore J. Flicker headed to Chicago in 1954 to check out the improvisational Compass Theatre by recommendation of his college friend Severn Darden. According to Flicker, the Compass was in terrible shape when he entered: the players were unprofessional, wore street clothes, had a lack of respect amongst their fellow performers, and were basically “all over the place.” However, Flicker saw potential in the company and in 1957 he launched his own wing of The Compass Players at the Crystal Palace in St. Louis. Mike Nichols and Elaine May arrived in St. Louis, and Flicker auditioned Del Close who had come highly recommended by Darden despite the fact that he had no previous improv experience. Ted hired Del on the spot after seeing him perform a fire-breathing act from the work of Flaminio Scala. They all felt that the “meandering” Chicago style of improv did not sustain the audience’s attention for an entire show. Realizing that new techniques were needed if improvisation were to transform from an acting exercise into an art form, Flicker began developing a new technique which he referred to as “louder, faster, funnier”… the audiences responded. His goal was to re-create the Chicago Compass without any of the people involved and without the experience of Viola Spolin’s teachings, Flicker wanted to invent his own way. Every morning after a show, he would sit down with Elaine May and examine what went wrong the previous night and then determine how it could be corrected. Through these sessions “The Rules” for publicly-performed improv were formulated, including the importance of the Who? Where? and What? of each scene needing to be expressed, avoiding transaction scenes, arguments, and conflict as they usually lead to dead ends, and playing at the top of one’s intelligence. “We came up with a teachable formula for performing improvisation in public in two weeks,” Flicker said. These new rules differed greatly from the rules of Viola Spolin, who wasn’t a performer and explored improv only as an acting exercise. This was a new era of improvisation.

Following the collapse of The Compass Players, Paul Sills launched the successor troupe “The Second City” in 1959. Nichols and May went on to become a smash hit on Broadway. Del Close moved back to Chicago and spent the rest of his life developing, refining, and experimenting with Ted’s rules. Del became an improvisational guru for three decades with a student roster that included Dan Aykroyd, John and James Belushi, John Candy, Bill Murray, Chris Farley, Andy Dick, Harold Ramis, Mike Myers, Bob Odenkirk, Stephen Colbert, Amy Sedaris, Andy Richter, Tina Fey, and all three founding members of the Upright Citizens Brigade (Matt Walsh, Matt Besser, and Amy Poehler.) Unquestionably some of the biggest and most influential names in the comedy world, and it all circles back to Flicker. “I never could have done it without the sheer force of Ted’s will and discipline,” Close said.

But what was next for Theodore J. Flicker? In the sixties he wed Barbara Joyce Perkins, television actress and star of dozens if not hundreds of commercials, and the two set their sights on Hollywood. Theodore’s first feature film The Troublemaker, which he co-wrote with Buck Henry, described as an “improvised adventure” and was a moderate success, and the next thing he knew the phone started ringing. He was offered to write a feature film to launch the careers of Sonny and Cher; however, when the project fell through Flicker instead penned a screenplay for Elvis Presley, the 1966 “racecar musical comedy” Spinout.

It was Paramount Pictures that gave Flicker a chance to write and direct a major motion picture studio film in 1967, the first movie Robert Evans greenlit as a studio executive. The President’s Analyst was a fantastic, on-target satire. James Coburn plays Dr. Sidney Schaefer, who is awarded the job of the President’s top secret psychoanalyst. When Dr. Schaefer’s paranoia sinks in and he realizes he “knows too much,” he decides to run away and the film becomes a fast-paced action adventure romp involving spies, assassins, the FBI, CIA, a suburban family station wagon, flower power hippies, and even a British pop group. An unusual sci-fi plot twist reveals the movie’s most surprising villain: The Telephone Company (referred to in the film as “TPC”).

Problems began when the FBI got ahold of the screenplay. Robert Evans claims he was visited by FBI Special Agents who didn’t appreciate their unflattering and incompetent portrayal in the film. When Evans denied their request to cease production, they began conducting surveillance on the film’s set. Evans refused their demands, but increasing pressure led to extensive overdubs during the film’s post-production phase: the FBI became the FBR, and the CIA became the CEA. Even the Telephone Company got wind of their negative portrayal in the film, and Evans believed that his telephone had begun to be monitored by either the Bureau or the phone company. Evans’ paranoia would ironically mirror that of James Coburn’s character in the film’s storyline.

The President’s Analyst hit theaters on December 21st, 1967, the same day as Mike Nichols’ The Graduate. Both films were instant hits and received critical and box office praise. Roger Ebert called The President’s Analyst one of the “funniest movies of the year.” However, two weeks later Flicker received an unsettling phone call from his agent who told him, “You’ll never work in this town again.” Apparently FBI head J. Edgar Hoover had seen the film and was outraged by 4’7” actor Walter Burke whose character name Lux (like Hoover, a popular brand of vacuum cleaner) as the head of the “FBR” was blatantly poking fun at him. J. Edgar called the White House who called Charles Bluhdorn at Paramount, who called Flicker’s agent to inform him they were pulling the movie from theaters immediately. “What the hell are you trying to do to me?” Bluhdorn said on a phone, “But we have a hit!” “What the hell do I care about your hit, I have 27 companies that do business in Washington?” A millionaire at age 30, Charlie Bluhdorn didn’t just own Paramount; he owned Gulf and Western, Madison Square Garden, and Simon & Schuster publishing. As Flicker delicately put it, “The shit hit the fan.” Overnight he was officially no longer part of Hollywood’s A-list. He and Barbara had to foreclose their home and his agent stopped returning his phone calls.

With the Hollywood movie studio doors now closed, the ‘70s found Theodore J. Flicker working as a character actor, director, and writer in television. While the studio system may have wanted nothing to do with him anymore, he was surprised how thrilled TV welcomed a former A-list filmmaker with open arms. He wrote and directed memorable episodes of The Mod Squad, Rod Serling’s Night Gallery (an episode titled “Hell’s Bells” in which he also portrayed the Devil), Banacek, The Man From U.N.C.L.E., and The Streets of San Francisco. In 1974 he co-created the hit police detective sitcom Barney Miller set in Greenwich Village. According to Flicker he and producer Danny Arnold came up with the premise in about an hour. The TV series was largely successful amongst viewers and even developed devoted following among real-life police officers; however, by the end of the first season Danny Arnold and Flicker had a falling out, which began a 10-year lawsuit.

There was a new and even more exciting outlet on television for Ted to show off his skills: “The Movie of the Week.” Not only were television movies largely successful and a cultural touchtone for a generation of Americans, but they allowed for more ambitious plots (often based on true stories), with material so daring and controversial that Hollywood studios never would have greenlit them in a million years. In 1977 Ted wrote and directed Just a Little Inconvenience for Farrah Fawcett and Lee Majors’ production company. His assignment was to write a TV movie that would accommodate the handicap of actor James Stacy, who had only four years previous lost his left arm and leg in a motorcycle accident in the Hollywood Hills. Stacey played double amputee Vietnam veteran Kenny Briggs, who returns to his favorite sport of skiing as part of his physical rehabilitation. The role earned Stacy an Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actor. The 1978 TV movie The Last of the Good Guys, written and directed by Ted, starred Robert Culp and told the story of four compassionate cops who convince the force that their fellow police officer is still alive after he loses his battle with leukemia so that his wife can collect his maximum pension. Los Angeles Times TV writer Cecil Smith called it “one of those rare films that combine stark tragedy with riotous comedy that you never see on television. Rarer still, it works.”

The 1970s also gave Ted a chance to make two low-budget, independently produced feature films outside of the Hollywood studio system. After famed B-movie producer Sam Arkoff had scored a smash with Three In the Attic which hit screen right at the height of the sexual revolution of the late ‘60s, he approached Ted to write and direct the pseudo sequel Up in the Cellar. The brilliant political satire about a student poet who seduces his college president’s wife, daughter, and mistress over lost financial aid (the tagline boasts “What a nifty way to get even”) was filmed entirely in New Mexico, and it was upon location scouting for this film that Ted first visited and fell in love with the land of enchantment, a place where he would later move and spend the rest of his life. Ted hired his oldest, best friend, Larry Hagman, to play the college president. Larry modeled the character Maurice Camber after his own father, attorney Ben Hagman. According to Ted’s wife Barbara “it was, of course, what became J.R.,” referring to (of course) Hagman’s role that followed on the 1980s prime time television soap opera Dallas. Ted recruited teen heartthrob Wes Stern, Altman muse David Arkin, Three in the Attic star Judy Pace, and like Larry Hagman, another old friend from his early days at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art: Joan Collins. The film’s atmosphere, tone, and cute cast of characters could easily be mistaken as a Wes Anderson film today. Sadly Up in the Cellar never got the proper release it deserved and was quickly swept under the rug.

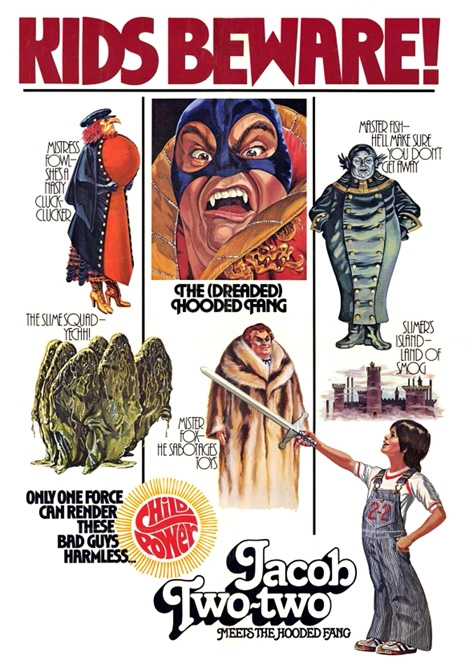

In the late ‘70s Ted and his wife Barbara traveled to Montreal to meet Canadian author Mordecai Richler, and Ted was handed the job of turning Richler’s children’s book Jacob Two Two Meets the Hooded Fang into a movie. Flicker jumped at the opportunity to write the screenplay and direct the story about a little boy who is taken to the strange nightmare world of the Hooded Fang, played by American football player and professional wrestler Alex Karras. Ted’s wife Barbara remembers, “The budget was shrinking day by day, and there were so many special effects and extraordinary costumes. I don’t know how they did it, but they did. It looked like a million dollar budget. Louis Furie did the score which was very edgy for a children’s picture, but I think it worked. And Teddy found all these great actors from Montreal theater to play the characters. They had a French-speaking Canadian crew who were excellent. Ted did speak pretty fair French, so it wasn’t a problem for him.” Jacob Two Two Meets the Hooded Fang only received a limited release in Canada and then quickly disappeared; however it’s rumored to be Ted’s personal favorite movie he worked on.

In 1982 Barney Miller ended a successful seven year run on television and even won a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Comedy alongside several other nominations despite the ongoing court battle. Finally in the mid-‘80s the lawsuit reached a multimillion-dollar settlement, which ruled in Ted’s favor. Now a rich man, Ted decided it was time to retire from the business forever; he and Barbara packed their bags and moved to Santa Fe, New Mexico where they would spend the rest of his life.

In September 2013 I was on tour across the southwest with video blogging collective Everything is Terrible! I had read on IMDB that Ted was now a sculptor living in Sante Fe with his wife of 48 years. Knowing that I would be in the Santa Fe area within the next few days, I wondered if there was any way I could possibly find Mr. Flicker and ask him all the questions that had been plaguing me for so long. I e-mailed Sante Fe-based art dealer and gallery owner Wade Wilson hoping he could put me in touch with the Flickers. The following day he e-mailed me back to let me know that he was “on the road” but assured me that he would forward my e-mail to Ted and Barbara. The day I left for the two week tour I received a call on my cell phone right as I was climbing into my Enterprise Rent-A-Car. It was Barbara Flicker, and she graciously invited me to their home for a personal tour of Ted’s sculpture garden. I was ecstatic. I would finally get to meet the man I had been idolizing for the past twelve years. What questions would I ask him? Would he even want to talk to me about anything other than his sculpture work?

Barbara assured me GPS would only get me lost so with her specific directions I arrived at “Flickfair” on time, and Ted warmly greeted me at the door. We hopped into a golf cart and he drove us through his beautiful four-plus acre private garden holding seventy-six works of art. All the sculptures were created entirely by Ted, and the rock paths handmade entirely by Barbara. The performer side of Ted emerged as he began telling me the stories behind all of his magnificent pieces of work. A very animated man for the age of 83, Ted shared sculptures inspired by his wife, important people and muses throughout his life, and Bible stories modernized with his own comedic flair. Some pieces such as one titled “Adam’s 2 Wives” Ted described as a Bible story he came up with himself. “This is not in the Bible, this is my invention, this is my Bible story, this is how I think it worked.” Another sculpture titled “Tamar” was inspired by the woman who married the patron saint of masturbation. The couple produced twins, one of whom Ted claims parented the line that produced King David and Jesus Christ. Ted admitted to taking Bible stories and readjusting the storyline if he didn’t like the ending because “Why not?” Another fact that was undeniable when viewing Ted’s work: Ted loved naked women. “All beauty in this world begins with women.”

After the sculpture garden tour, Ted and his wife invited me into their home for lunch; Barbara had made us all fresh tomato sandwiches. We sat and talked. “How come you decided to move to New Mexico?” I asked him. Ted told me he first discovered and fell in love with New Mexico while location scouting for a film. “Ah, Up in the Cellar… I love that movie!” I exclaimed, thus outing myself as a fan of his film work for the first time that afternoon. He was surprised that I had ever seen it, or any of his films for that matter, and the conversation eventually led us to talking about The President’s Analyst. “You can ask me anything you want,” Ted said before dishing out all the juicy details, much of it information that helped me write the article you are reading right now. When I asked him about his improv background and told him that I had studied and learned the teachings of Del Close, Ted boasted, “I taught Del Close improv!” After detailing his drama with J. Edgar Hoover Ted said that had he known at the time that Hoover was a crossdresser he would have incorporated that into his movie as well. My mind was blown.

“So how come you hate the phone company so much?” Ted explained, “Everybody universally hated it then, everybody universally hates it now, nothing’s changed.” Ted detailed his own war with Verizon over the poor service and lack of cell phone reception at the Flickers’ home in Santa Fe. The war escalated to the point that Ted even threatened to take out a full-page ad in The New Mexican and denounce Verizon as “lousy, miserable, lying bastards.” The Verizon customer representative told Ted he would have to call him back. The following afternoon the representative called Ted from a “secure” line and gave him the direct phone number to someone very high up in the company. “I know you who are, Mr. Flicker, and I’m going to help you.” Once again, a real life incident ironically mirrored one of Ted’s own movies.

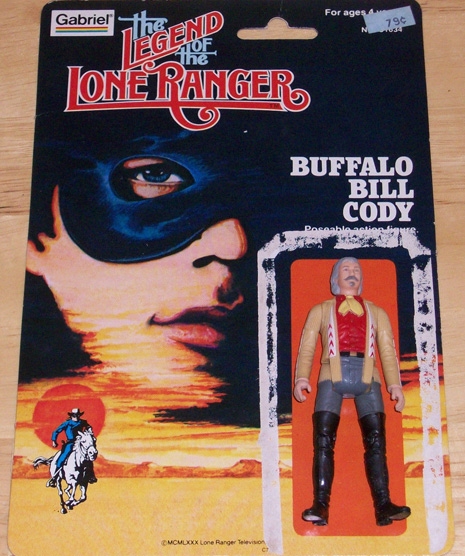

Ted told me it was time for his afternoon nap, but before I left he showed me his garage where he kept all the memorabilia from his Hollywood film and television years: movie posters, lobby cards, b&w production stills, studio memos, and clapperboards. But one particular item on the wall stood out as extraordinary and I had to ask about it. “I’m the only one I know who has an action figure of himself,” Ted said in reference to his role in the 1981 film The Legend of the Lone Ranger, which happened to spawn a line of action figures created by the toy company Gabriel. The action figure line included the characters of Tonto (played by Twin Peaks actor Michael Horse who became a lifelong friend of Ted after the filming), Butch Cavendish (as played by Christopher Lloyd), and Buffalo Bill Cody as played by Ted. Ted sent me back onto my road trip with an autographed DVD of The President’s Analyst and thanked me for making his day.

In September 2014 one year after my visit with the Flickers, Ted and Barbara attended an evening art opening at Wade Wilson’s Gallery in Santa Fe. Guy Cross, the editor and publisher of THE Magazine snapped Ted’s portrait that night not knowing it would be the final picture of him ever taken. Later that evening when they got home, Barbara found Ted lying on the floor, and minutes later he passed away. Ted had been in and out of the hospital for years with complications of a lung infection that he believed was brought about by chemicals found in the clay he used to sculpt. Ted left behind his wife Barbara, his two brothers Dr. Marvin Flicker and Robert Flicker, and his faithful German Shepherd. He was 84 years old.

Ted Flicker lived a long and incredible life, and he passed away peacefully as an intensely happy man. While he may not have gotten the opportunity to make all the other pictures he wanted to make, he still leaves behind a thoroughly impressive body of work which sits waiting to be discovered by film fanatics of tomorrow. His contribution of “The Rules” for improvisational theatre is still being taught every day and will continue to catapult the future generation of comedians for decades to come. But with all those accomplishments under his belt, Ted still referred to sculpting as the most profoundly satisfying thing he’s ever done. “And I’ll tell you another thing that’s fun about sculpture,” Flicker said. “I never have to show it to some schmuck from the studio.”

Special thanks to Barbara Flicker, David Ewing (whose documentary Ted Flicker - A Life in Three Acts is currently seeking distribution), and Nathaniel Thompson.

Ted Flicker in his studio, 2011. Photo by Elliott Mcdowell