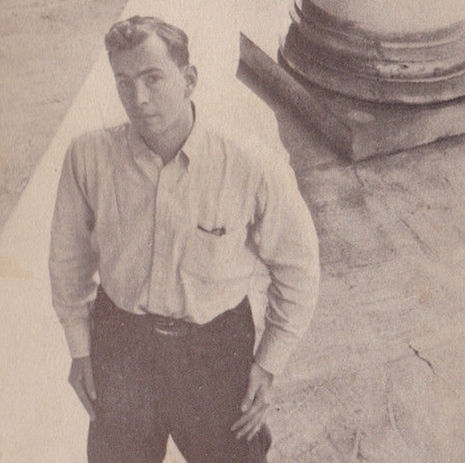

Jack Kerouac, 1953

“What did you and Jack do?” Allen Ginsberg asked Gore Vidal one cold January night in 1994.

“Well, I fucked him,” Vidal was pleased to reply. On the night of August 23, 1953, the two men of letters had banged one out in a Chelsea Hotel room following a Greenwich Village bar crawl. Kerouac published a fictionalized account of the assignation in The Subterraneans but, aside from a morning-after moment of “horrible recognition,” he left out the sex. Vidal was annoyed, and said so:

I challenged Jack. “Why did you, the tell-it-all-like-it-is writer, tell everything about that evening with Burroughs and me and then go leave out what happened when we went to bed?”

“I forgot,” he said. The once startlingly clear blue eyes were now bloodshot.

Palimpsest, the first of Gore Vidal’s two memoirs, fills in the lacuna with a detailed record of the evening’s events. It began with William S. Burroughs. Kerouac and Vidal had met before, and in a 1952 letter to Kerouac, Burroughs expressed interest in meeting the author of The Judgment of Paris:

Is Gore Vidal queer or not? Judging from the picture of him that adorns his latest opus I would be interested to make his acquaintance. Always glad to meet a literary gent in any case, and if the man of letters is young and pretty and possibly available my interest understandably increases.

Gore Vidal on the back cover of The Judgment of Paris, 1952

The three writers met at the San Remo bar the following year, after Burroughs’ return from Mexico. Kerouac, Vidal writes, “was manic. Sea captain’s hat. T-shirt. Like Marlon Brando in Streetcar.” Burroughs asked about a Turkish bath in Rome that Vidal had described in The Judgment of Paris. They moved on to Tony Pastor’s, a lesbian bar; afterwards, Kerouac swung around a lamppost out front, “a Tarzan routine that caused Burroughs to leave us in disgust.” Vidal was ready to go back to his father’s apartment uptown, but Kerouac had a different notion:

“Let’s get a room around here.” The first law of sex is never go to bed with someone drunk. Corollary to this universal maxim was my own fetish–never to have sex with anyone older. I was twenty-eight. Jack was thirty-one. Five years earlier, when we first met, I would have overruled the difference, but I had also arbitrarily convinced myself that Conrad’s “shadow line” extended to sex: So from the age of thirty on, a man or woman was, for my purposes, already a corpse–not that I ever had much on my mind when it came to sex with men. In my anonymous encounters, I was what used to be called trade. I did nothing–deliberately, at least–to please the other. When I became too old for these attentions from the young, I paid, gladly, thus relieving myself of having to please anyone in any way. But now here I was stuck with Jack, who had certainly once attracted me at the Metropolitan when that drop of clear water slid down his cheek. Now there was real sweat. I stared at him. We were the same height and general build. With some misgiving, I crossed the shadow line.

At the nearby Chelsea Hotel, each signed his real name. Grandly, I told the bemused clerk that this register would become famous. I’ve often wondered what did happen to it. Has anyone torn out our page? Or is it still hidden away in the dusty Chelsea files? Lust to one side, we both thought, even then (this was before On the Road), that we owed it to literary history to couple.

I remember that the bathroom was near the entrance to a large double room. There was no window shade, so a red neon light flickering on and off gave a rosy glow to the room and its contents. Jack was now in a manic mood: We must take a shower together. To my surprise, he was circumcised. [...]

Where Anaïs and I were incompatible–chicken hawk meets chicken hawk–Jack and I were an even more unlikely pairing–classic trade meets classic trade, and who will do what?

Gore Vidal, 1948

“Jack was rather proud of the fact that he blew you.” Allen sounded a bit sad as we assembled our common memories over tea in the Hollywood Hills. I said that I had heard Jack had announced this momentous feat to the entire clientele of the San Remo bar, to the consternation of one of the customers, an advertising man for Westinghouse, the firm that paid for the program Studio One, where I had only just begun to make a living as a television playwright. “I don’t think,” said the nervous advertiser, “that this is such a good advertisement for you, not to mention Westinghouse.” As On the Road would not be published until 1957, he had no idea who Jack was.

Thanks to Allen’s certainty of what Jack had told him, I finally recall the blow job–a pro forma affair, which I put a quick stop to. At what might nicely be called loose ends, we rubbed bellies for a while; later he would publish a poem dedicated to me: “Didn’t know I was a great come-onner, did you? (come-on-er).” I was not particularly touched by this belated Valentine, considering that I finally flipped him over on his stomach, not an easy job as he was much heavier than I [...]

Jack raised his head from the pillow to look at me over his left shoulder; off to our left the rosy neon from the window gave the room a mildly infernal glow. He stared at me a moment–I see this part very clearly now, forehead half covered with sweaty dark curls–then he sighed as his head dropped back onto the pillow. There are other published versions of this encounter: in one, Jack says that he spent the night in the bathroom. On the floor? There was a shower but no tub. In another, he was impotent. But the potency of other males is, for me, a turnoff. What I have reported is all there was to it, except that I liked the way he smelled.

Alas, there is no sex tape, but you can watch part one of the fascinating Omnibus profile of Vidal below (part two here).