The Clash busking in York, 1985

In its official version, the story of The Clash ends with the firing of lead guitarist Mick Jones in 1983. Though founding members Joe Strummer and Paul Simonon subsequently led a five-piece version of the group until the first months of 1986, it is not a polite thing to mention at parties. The 384-page coffee-table book The Clash

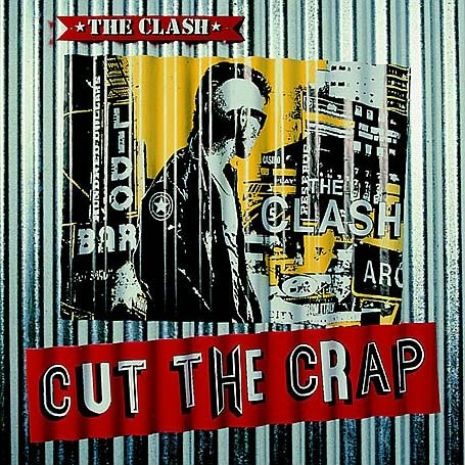

devotes less than a single page to the final two and a half years of the band’s career, and the 1985 album Cut The Crap has been left out of every Clash box set to date. In the words of Rolling Stone, “It doesn’t count, and the whole thing has basically been erased from history. The Clash as we know them ended at the 1983 US Festival.” The new Clash met the same fate as the new Coke.

While no one would dispute that it was a poor choice to fire Mick Jones, the Clash did a few things worth remembering between 1984 and 1986. Determined to make a radical break with stardom, they went on a busking tour of the U.K. that included a stop in the parking lot of an Alarm show, where the headliners reportedly came out to watch. Strummer never sounded so fired up in interviews as he did in 1984, and rock critic Greil Marcus reported that, despite the new Clash’s shortcomings, he’d “never seen Strummer more exhilarated, or more convincing” than at a January 1984 show in California.

Strummer and Simonon interview, 1984 (part two)

Danny Garcia’s documentary The Rise and Fall Of The Clash, a whodunit about the breakup, is the first movie to shed light on this bizarre period. Based on interviews with original members Mick Jones and Terry Chimes, late-period members Pete Howard, Nick Sheppard, and Vince White, comrades Pearl Harbor, Viv Albertine, and Vic Godard, and others from the band’s circle, the movie largely focuses on the role of manager Bernie Rhodes.

The Rise and Fall of The Clash trailer

Evaluations of Rhodes’ actual contribution to the band vary widely, but most parties agree that Strummer trusted the manager while Jones did not. The Clash fired Rhodes in 1978—they were managed by big-timers Blackhill Enterprises during the recording of London Calling and Sandinista!—but they hired Rhodes back in 1981. “Joe wanted Bernie back because there was no excitement in the situation with Blackhill and Joe needed to have someone like Bernie around to give him confidence,” Simonon says in the coffee-table book.

The documentary makes it clear that Rhodes exploited Strummer and Simonon’s resentment of Jones’s “rock star” behavior (dating models, showing up late, etc.) to force Jones out and seize control of the band. This part of the story reveals unfathomable dimensions of weirdness. For instance, according to Jones, in the days before he was fired, the band gathered in Rehearsal Rehearsals to write new material. There, Jones says, ruthless manager Rhodes had the Clash working on the follow-up to the platinum-selling Combat Rock, an album of. . . New Orleans jazz?

Rhodes’ ascendancy culminated in the recording of Cut the Crap, an utterly strange hybrid of contemporary punk and hip-hop styles, co-written and co-produced by Strummer and Rhodes. Drum programming replaced Pete Howard’s playing, and much of the material is covered with haphazard synth bleats that sound like a cat dancing on a Casio. There is a (perhaps apocryphal) story that a contemporary British music magazine dispatched Cut the Crap with the shortest record review ever printed: “Cut the ‘cut the.’ ” Side two, however, has its moments:

Cut the Crap side two, track one: “This Is England”

Cut the Crap side two, track two: “Three Card Trick”

There is a touching moment near the end of The Rise and Fall of The Clash. In a denouement worthy of a romantic comedy, Strummer, having suddenly realized he was mistaken to trust Rhodes and that Mick Jones had been his true and honest mate all along, rushes to Jones’s house and finds his former bandmate waiting for a cab to the airport. They share a spliff, Strummer jumps in Jones’s cab, and together they fly to Nassau. Jones wouldn’t come back into the Clash, because he’d formed Big Audio Dynamite, but Strummer and Jones would collaborate on BAD’s second album No. 10, Upping St.

Here’s little-known footage of The Clash 2 performing “Brand New Cadillac” at the 1985 Roskilde Festival, one of their final performances: