Last night before diving greedily back into binge watching Daredevil, I was extremely happy to see that Netflix was streaming Toby Amies’ 2013 documentary, The Man Whose Mind Exploded—and even featuring it prominently on their “new releases” homepage. I first saw the film last summer and it was easily one of the very best things I saw last year, as I enthusiastically related to our readership at the time. However, at that point to actually see the film yourself, you’d have had to have gone to the iTunes store, something that I’m reasonably sure that only a tiny percentage of you bothered doing… I know, I know, give me convenience or give me death. Although it’s difficult to imagine too many things easier than simply downloading something as you just sit on your ass otherwise, now that Netflix is ready to pump this extraordinary film right into your home like water or gas with the mere push of a button or two, you’ve got no excuse. I wanted to republish this interview with Toby Amies from 2015 to get this film on our readers’ radar screens again, in hopes that they’ll be watching it later tonight on their HDTV screens. We’re in the Age of Consumer Enlightenment, people. Why not take full advantage of the modern world before President Trump starts World War III?

Anyway, I think it’s very safe to say that you’ve never seen a story like this one before.

*****

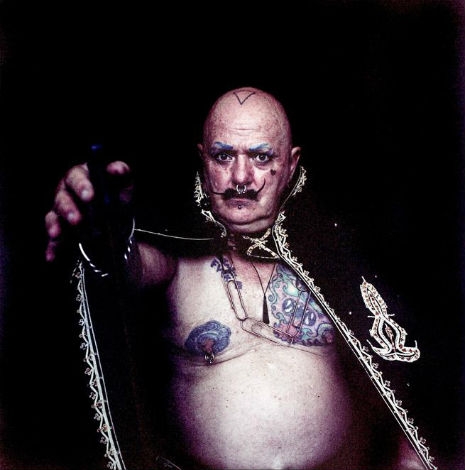

The titular focus of Toby Amies’ extraordinary, sensitive and lyrical 2013 documentary, The Man Whose Mind Exploded is one Drako Zarharzar, who is, when we meet him, 76 years old, exotic, theatrical and utterly flamboyant, but due to brain injury, he cannot remember much of anything about his long and eventful life. He “knows” for instance, that he knew—and posed for—Salvador Dali and that he once had a career onstage in show business, but he doesn’t remember what happened yesterday. Or who someone is from one day to the next.

Drako lived “completely in the now,” his mind unable to create new memories, a condition called “anterograde amnesia.” In order to get around this obviously monumental handicap, he created a 3D collage—a sprawling, kaleidoscopic, pornographic hoarder’s mobile hanging from string around his tiny, unhygienic flat in Brighton—to compensate. When one entered Drako’s cave-like dwelling, they were in effect entering his autobiography and mind. Additionally he modified his own body with Memento-like tattoos, including his motto/philosophy “TRUST ABSOLUTE UNCONDITIONAL” which was how he saw—or at least coped with—the outside world as he encountered it.

The Man Whose Mind Exploded, beyond being a moving portrait of an extremely eccentric (and unwell, yet happy) character facing life against such daunting headwinds, brings up all kinds of philosophical notions about time, memory (or complete lack thereof) and gives the viewer a great sense of empathy for what it’s like to care for someone who literally cannot remember who you are each time they encounter you.

The soundtrack, which is gorgeous, was done by Adam Peters (who I think is a musical genius).

I asked Toby Amies—who you might recall from MTV in the 1990s—some questions via email.

Richard Metzger: How did you meet and befriend Drako?

Toby Amies: I first saw Drako in Kemptown in Brighton, he swished past me on his bike in a cape like a Surrealist superhero! Then I met him properly through a mutual friend David Bramwell when I made a film for his band Oddfellow’s Casino that starred Drako. When I saw inside Drako’s extraordinary and bizarre home, where every room was filled with a sprawling 3D autobiographical collage, it reminded me of the so-called “outsider” art I’d seen and studied in the US. Ever since visiting S.P. Dinsmoor’s “Garden of Eden” in Lucas, Kansas I’ve long been fascinated with what I call “automonuments” where people, usually men, build tributes to themselves, but there was something very sweet and intimate about Drako’s home work, as it was designed to remind him of his self.

Drako and Toby Amies

Yes, he’s a bit of an outsider interior decorator, isn’t he? How long before you started visiting him with a camera? Was he okay and cooperative about you making a film from the start?

I began filming him on the second day I met him. Initially it was disconcerting, because of his mantra “Trust Absolute Unconditional,” he would happily agree to anything that we asked him. And this made it obvious to me from the start that there was a tremendous responsibility associated in working with someone who had chosen to believe, as a result of brain damage, in a completely benevolent universe. The onus was on us to make sure we did right by him. There were times when Drako clearly tired of my questions, and in one instance this is recorded in the film. Because I’d made a radio documentary about him first, we contacted his immediate family and his closest friend to ensure that we had a consensus that it was okay by the people who cared most about him that we were recording and documenting him. Consequently this tight community of concerned individuals became part of the film, because one of the things it explores is what our responsibility is towards someone who may not be able to care for themselves, and from a filmic point of view they are exceptional, funny and kind people.

Although there is the Salvador Dali story that he keeps repeating, and the photo of him in the singing group, there’s precious little of Drako’s past life and career that’s touched upon in the film. Was this a deliberate decision on your part, to keep Drako, as it were tabula rasa and in his “eternal now” for the audience, or was it more a matter of him having precious few memories of his past that he could even tell you about?

In the early stage of the editing we found that much of the biographical material was interesting from a cultural and historical point of view but looked like pretty boring cinema, or, as I call it: “television.” What was much more compelling to me and my editor Jim Scott was the actuality, the experience of being in Drak’s never-ending now. Film is such a great medium for communicating the emotional immediacy of a situation and I wanted to make the audience feel what I felt in visiting that bizarre and wonderful environment, though no film, could come close to the olfactory experience of that place, it would defeat even the greatest practitioners of Odorama. The biographical elements that remain are usually there to provide context to understand the comedy, battles and struggles that happen in the moment. Drako’s memory worked in such a way that whilst he had access to memories of events that happened before the accident that damaged his hippocampus, he remembered them in a way that seems more biographical than autobiographical. And also he would often tell the same story in exactly the same way no matter the circumstance. Often ending it with a very sweet “Did I tell you that already?”

He might have lost part of his memory but his manners were always immaculate and likewise his sense of humour was always present. That became the foundation of our friendship, our ability to make each other laugh, and what better version of “the now” is there than two people laughing with each other? Those were the moments I wanted to record and share, the ones where the greatest empathy is possible. In making the film I was very careful never to present Drako as an object except when we see others react to him on the street. It was important to keep the audience’s relationship with him subjective, even though to many folk he might look weird and behave in a bizarre manner, I wanted to make sure he was included in our definition of what it is to be human whilst expanding the possibilities of that definition a little. In other words, he’s one of us, but broadens the definition of “us” in the process.

The body modification and tattooing that he was into—is this something that happened before or after the events that stole his memory?

Even though when I knew him, Drako was in the process of externalising his memory to compensate for the loss of inside his mind, hence the film’s title, I think it’s fair to say that he had started the writing of his story on himself long before. Some of his tattoos were to remind him of things said to him in a coma, but most were there before, and he was a pioneer in piercing and extreme tattooing long before they became ubiquitous. His superb “ram fucking the moon” body tattoo was done by the properly legendary Alex Binnie. Even though I didn’t meet him then I am pretty sure Drako and I were first in the same room together at the Stainless Steel Ball, a get together organized by the Piercing Association of the UK in Brighton, waaaay back in the day.

Do you think that it was in fact brain damage that caused his perpetual sunny outlook on life?

Well, I can only offer an opinion, but following a conversation with our superb Neuropsychological Consultant Professor Martin Conway I wondered whether Drako had in a sense hypnotized himself to cope with the loss of so much of what he used to take for granted. As his friend Mim suggests in the film, perhaps the mantra, said to him in his second coma: “Trust Absolute Unconditional” had transformed from a question into an answer. This upset me for a bit, the idea that Drako had to hypnotise himself to happiness, but then I thought about the meaningless of my existence as I hurtle down the shrinking highway of my life towards inevitable death; and I thought don’t we all in some sense hypnotize ourselves into thinking that in spite of our grim fate there is still a point, of our own invention, to life, in spite of death? Also as his nephew Marc says, within his ability to do so, Drako lived how he wanted, and did exactly what he wanted to do, without harming anyone else in the process, which is a lifestyle that would make most folk happy I reckon.

When you pointedly ask him if he remembers you, he says that he doesn’t, that “you’re new every time.” Did you have to establish who you were each time you visited him or did he kind of recall you after a while? Like when his sister arrives after some time and starts speaking French to him, he seems to immediately know who is speaking and responds enthusiastically (without seeing her, she’s on the intercom outside of his flat)

There was a good lesson there for me—even though I knew Drako had a unique mind and had suffered serious brain trauma, who the fuck was I to decide how consistent his memory loss should be? I had the sense that he had a rough idea of who I was after several visits and was comforted to see my name appear on notes in the house, but then there were moments even late in the relationship where I was clearly someone new. I dealt with that by thinking that pretty much any opportunity that teaches you how little you matter in a wider context than your own head is helpful, and by following Drako’s lead and trying to be as present as possible in the moment. That made the filming intense, difficult, and exciting, a kind of improvisational theatre that put my background as a photographer and TV presenter to effective use. Drako still had access to memories from before his accident, but could not record ones effectively afterwards. He described it in terms of a magnetic tape machine, the playback head works, but the record doesn’t. So Anne existed for him but the time they spent together didn’t so much. Perhaps that ended up being harder for the people who wanted him to remember the time they had together, their shared narrative, than for Drako himself. Maybe that’s one of the reasons I made the film, to preserve and share my part of that extraordinary story.