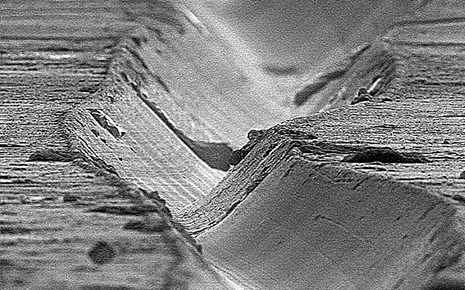

Yesterday Dangerous Minds brought you some incredible close-up electron microscope footage of a needle moving across the grooves of a record.

That footage jogged a fuzzy childhood memory of watching That’s Incredible!, a Ripley’s Believe It Or Not style program that aired on ABC from 1980-84, and seeing a man who could identify music simply by looking at the grooves on a record.

I had to consult the Internet to make sure I didn’t dream that up, but this man does in fact exist and his name is Dr. Arthur B. Lintgen.

A 1982 TIME article describes Dr. Lingten’s bizarre talent:

With the label and other identifying marks covered, of course… Lintgen simply holds a disc flat in front of him, turning it slightly this way and that and peering along its grooves through his thick glasses. After a few seconds he calmly announces, as the case may be, “Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring” or Strauss’s Atpine Symphony,” or “Janacek’s Sinfonietta.”

A passionate music buff and audiophile, Lintgen (pronounced Lint-jen) has been regaling friends with the stunt for five years, ever since being challenged at a party and finding, to his surprise, that he could do it.

Performing recently for a television crew from That’s Incredible! he scored 20 for 20 in a demonstration set up by Temple University Musicologist Stimson Carrow.

Lintgen, who has been called a savant, applies his encyclopedic knowledge of classical music to the “quiet” and “loud” portions of the disc, which show up as darker or lighter “grooves,” to make an educated guess as to what a particular piece might be. A 1981 New York Times article explains:

How does he do it? All is explainable—up to a point. First, Dr. Lintgen is a dedicated audiophile with an extensive knowledge of the record catalog past and present. He can identify only music that he knows, and he guarantees a high rate of success only in orchestral music ranging from Beethoven to the present.

“I have a knowledge of musical structure and of the literature,” he said. “And I can correlate this structure with what I see. Loud passages reflect light differently. In the grossest terms, they look silvery. Record companies spread the grooves in forte passages; they have a more jagged, saw-tooth look. Soft passages look blacker.

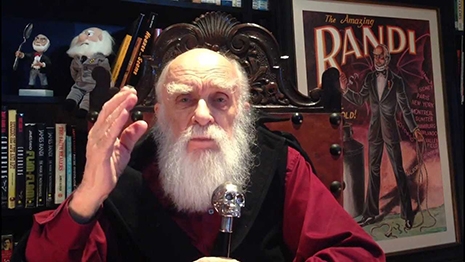

Acclaimed skeptic James Randi tested Lintgen and concluded,“certainly, Arthur Lintgen comes as close to (a real magician) as I ever hope so see!”

The Amazing Randi put Lintgen to the test.

This Los Angeles Times article details the astounding showdown between Randi and Lintgen:

Although Randi was skeptical about Lintgen’s claims, he nevertheless asked Lintgen if he would be willing to participate in a scientifically controlled test. Lintgen agreed and thereby outlined his talent as follows:

He could only identify post-Beethoven classical music that was fully orchestrated. He could not identify spoken-word recordings or the works of contemporary classical composers who were relatively unknown.

Since Lintgen had put some limitations on his abilities, Randi believed that it was a claim that could be easily tested. Randi designed a controlled test in which he assembled a number of popular recordings, carefully covered the labels and matrix numbers, slipped them into unmarked jackets and had a disinterested aide shuffle them.

A number of “controls” were placed in the test. These were two different recordings of Stravinsky’s “Le Sacre du Printemps,” an Alice Cooper recording and a spoken-word recording.

These controls were mixed in with Ravel’s “Bolero,” Tchaikovsky’s “1812 Overture,” Holst’s “The Planets,” a pair of famous Mozart symphonies and other known classical recordings. As a further precaution, Lintgen was not provided a list of the recordings used in the test.

Lintgen, a very nearsighted man with thick glasses, took the first recording off the pile, removed his glasses and placed his eye at the edge of the recording and slowly rotated it. He looked slightly puzzled.

“I think that this is Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony,” he said. “However, there is an extra movement in here that I can’t understand. Is it a strange recording?”

Randi replied that he could offer no clues. Lintgen examined it further and declared, “Yes! It is the Sixth Symphony, but it also contains an additional overture that I will guess is the ‘Prometheus Overture.’ “

Lintgen was right.

He then pulled out another recording from the batch and identified it as Stravinsky’s “Le Sacre du Printemps.”

At that time, Randi did not know if the recording that Lintgen was holding was indeed Stravinsky’s “Le Sacre du Printemps,” but he knew that there were at least two different copies of that piece in the controlled test. At this point, Randi knew the man had the talent.

Lintgen pulled out the next recording and said with a wink, “Ah. You are trying to fool me! This is a different recording of the same piece.”

He proceeded to provide further information about the recording. “This version was performed by a German orchestra,” he stated.

An astonished Randi could hardly contain his reaction. “How could he possibly know whether the orchestra was French or German?” he wondered to himself!

Lintgen went on to correctly identify the rest of the classical recordings in the test.

He did declare that one of the recordings was “disorganized and gibberish.” That one turned out to be the Alice Cooper recording.

One other control amused Lintgen. “This is not instrumental music at all,” he declared, squinting at it closely. “I’d guess that it’s a vocal solo or spoken-word recording of some kind.” That recording was one of the controls, an instructional record titled, “So You Want to be a Magician?”

After the test was completed, Randi asked Lintgen to explain how he identified the recordings.

Lintgen told Randi that he was not picking out individual notes or reading the music from the grooves. “I can’t imagine anyone doing that,” he said.

The trick, Lintgen explained, is to examine the physical construction of the recording and look at the relative playing time of each one of the movements or separations on the recording.

According to Lintgen, a Beethoven symphony will have a slightly longer first movement relative to its second movement, while Mozart and Schubert would compose in such a fashion that each movement in many cases would have the same number of bars. Beethoven, however, had set out in a new direction and that changed the dynamics of the recording. In addition, if there was a sonorous slow beginning, one could look at the recording at that point and see a long undulating groove that would not contain the sharp spikes that would identify sharp percussion.

Alice Cooper, deemed “disorganized and gibberish” according to groove-reader Arthur Lintgen.

Once it was disclosed that his powers were an uncanny ordinary sense perception, rather than extra-sensory perception, the mass media and the public quickly lost interest in Lintgen.

Still, what an unbelievable talent… Try doing that with the waveforms of your mp3s. As they said back in 1982: “That’s incredible!”