Piedra Rodante was the Mexican version of Rolling Stone that existed in late 1971 before shutting down as a result of intense pressure from the Luis Echeverría administration. The magazine was in Spanish, of course, and the content was a combination of original reporting on Mexican issues alongside translations of recent content from the U.S. version of Rolling Stone. It existed for only eight issues, and its demise arguably heralded the end of La Onda Chicano, a rock music movement that drew inspiration from La Onda (The Wave), the name for the countercultural stirrings in Mexico.

For reasons I cannot fathom, the existence of Piedra Rodante has been all but written out of the Rolling Stone narrative.

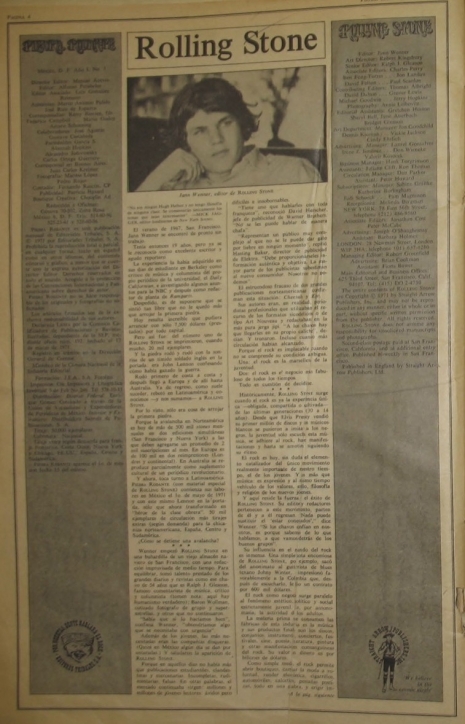

Details on Piedra Rodante are somewhat scarce. All eight issues are available as an image archive at the website for the Stony Brook University. Google suggests that the picture below is of the magazine’s editor, Manuel Aceves, but I don’t know and don’t have any easy way of knowing. (The page it came from lost its 3rd-party hosting privileges at some point.)

Is this Manuel Aceves, editor of Piedra Rodante?

Stony Brook University has an admirable summary of the magazine’s brief existence and the social stirrings to which it was linked. The key points of reference that are necessary to understand are the Tlatelolco massacre in late 1968 in Mexico City, in which the Gustavo Díaz Ordaz regime brutally suppressed the thousands of students protesting the Olympics to be held in Mexico City a little more than a week later, leading to at least 300 fatalities and 1,300 arrests. The Olympics had to go on.

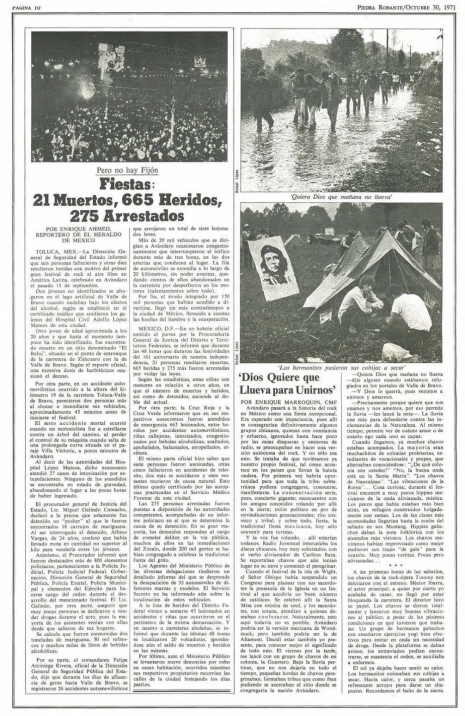

On June 10, 1971—Corpus Christi—there was a similarly brutal crackdown when government-trained paramilitaries—known as the Halcones, or “Falcons”—attacked a protest march outside the Santo Tomás campus of the National Polytechnical Institute. After a first wave of paramilitary soldiers attacked the protesters with bamboo and kendo sticks, “los Halcones” then attacked the students with high-caliber rifles for several minutes. The death toll was roughly 120—the event became known as El Halconazo, or the “hawk strike.”

The magazine wasn’t up and running yet, however. During the magazine’s brief duration, on September 11–12, 1971, occurred one of the largest and most significant rock and roll gatherings in Mexican history, the Avándaro Rock Festival. Avándaro had an entirely domestic roster of bands and was specifically modeled after Woodstock, which had taken place two years earlier. The event drew some 200,000 people, if not many more, and pretty much wigged out the authorities, which enforced a crackdown directly afterward that led to the demise of the magazine.

Here is part of Stony Brook’s summary of Piedra Rodante’s brief lifespan:

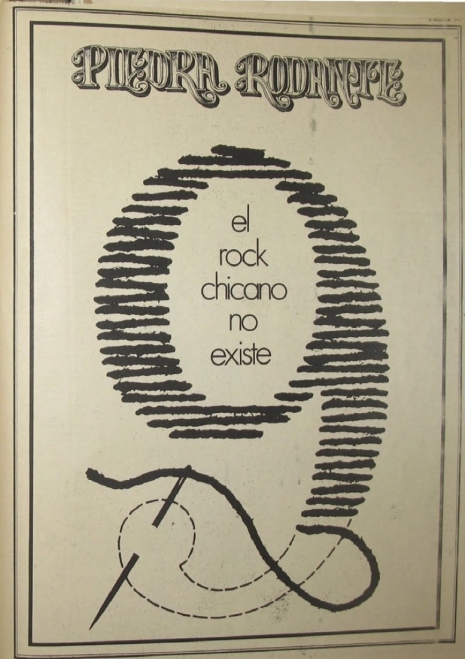

Mexican middle-class youth yearned to be recognized participants in the global counterculture. By around 1967, the cultural landscape of these youth reflected those yearnings, as expressed now not only through locally produced music but also through fashion, aesthetic choices, and a new youth argot. Collectively, this incipient countercultural movement was labeled within the media as “La Onda” (The Wave). Although intellectuals and more radical students generally regarded La Onda with a certain degree of disdain—judging it as “mere imitation” of a more authentic youth counterculture found abroad—in truth, the values and aesthetic choices linked to La Onda had seeped into all corners of youth cultural practice more broadly. This became especially apparent during the massive student-led demonstrations in the summer-fall of 1968, which culminated in a violent crackdown by the government on October 2 (“Massacre at Tlatelolco”). In the aftermath of the crackdown, La Onda was transformed by a generation of youth whose optimism had been shattered by the repression of a one-party state, into a vibrant vehicle for national protest.

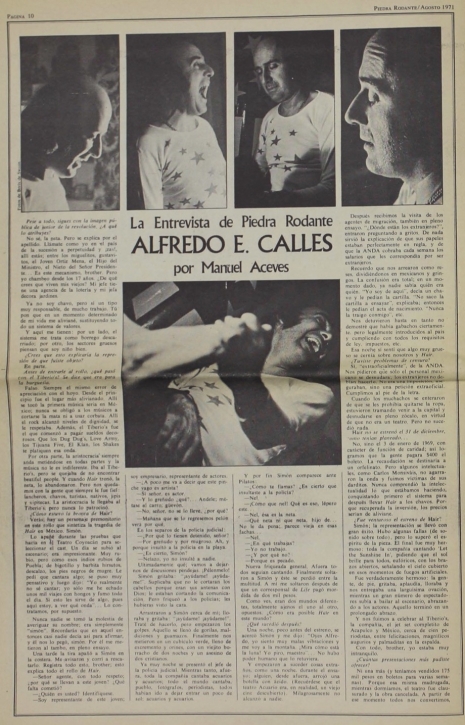

In late 1970, Manuel Aceves, who was at the time working successfully in advertising, decided to give up his job and put together a magazine similar to Rolling Stone. Imitating Rolling Stone’s own take on the New York Times motto “all the news that’s fit to print,” by using “all the news that fits,” Aceves chose “el periódico de la vida emocional” (the newspaper of emotional life), meant as a pun on “el periódico de la vida nacional” (the newspaper of national life), which was the motto of Excélsior, one of Mexico’s two major newspapers at the time.

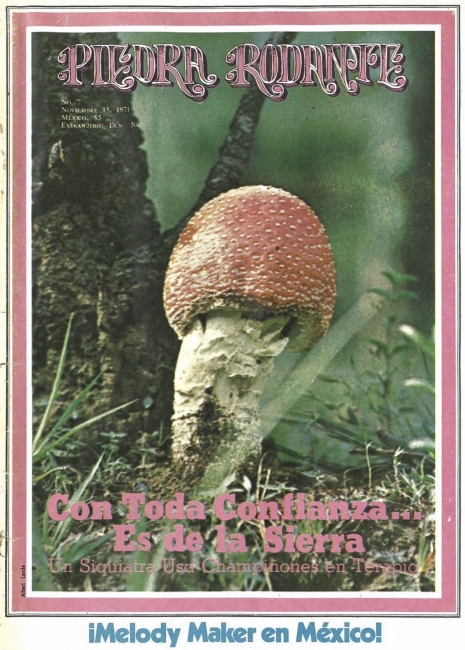

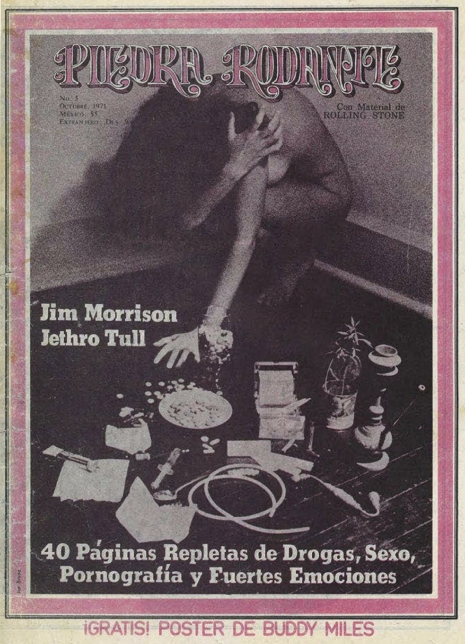

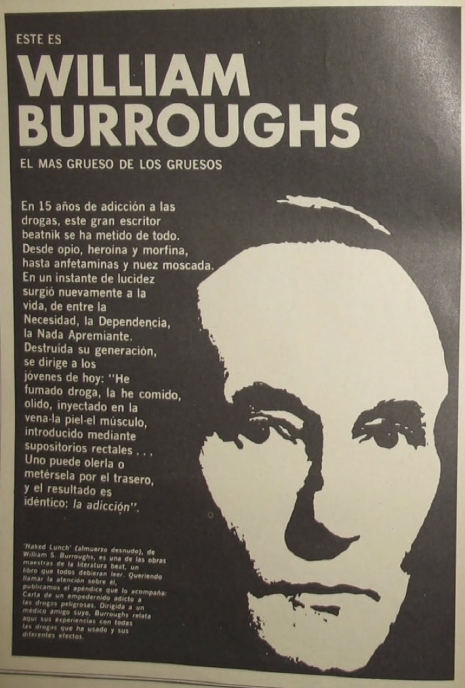

Aceves liked testing the boundaries of what could be published in Mexico, and Piedra Rodante’s reporting on the counterculture, as well as events and protests related to the regime crackdown after the Tlatelolco episode, soon reached a point the government of President Luis Echeverría (1970-76) was not willing to accept. After only eight issues, La Piedra, as it had become known, was abruptly shut down. Still, the magazine did manage to devote a whole issue to the 1971 Avándaro music festival, Mexico’s equivalent to Woodstock, and by then had become a vibrant forum for young writers interested in the new musical and cultural milieu of La Onda, at home and abroad.

The rise of La Onda Chicana led to some extravagant expectations of a new branding of Mexico as a locus of exciting musical and artistic currents. Hand in hand with that was the commercialization of the music scene, a process of which the most prominent Anglo American participant was Polydor, by far.

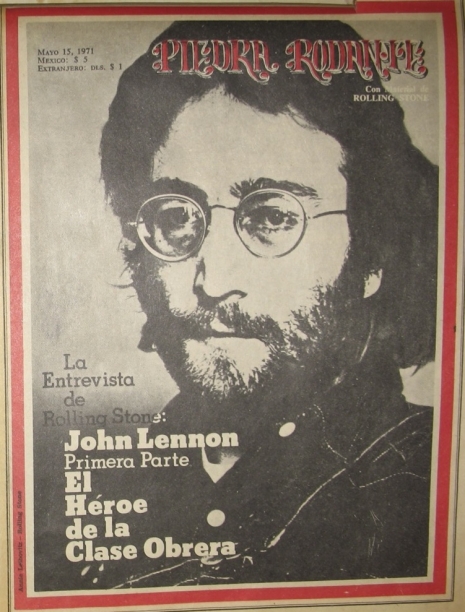

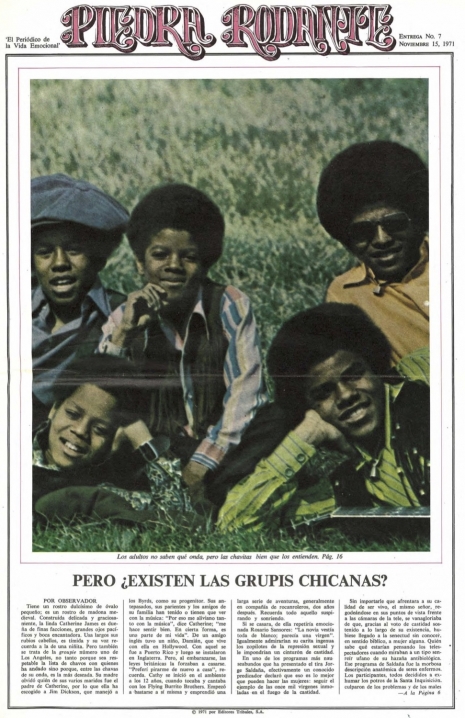

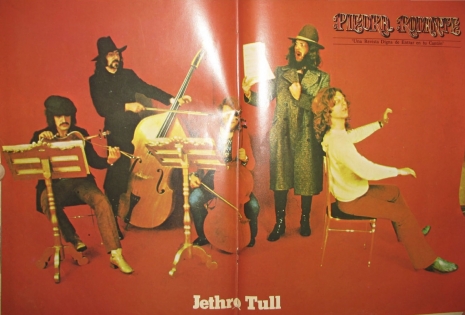

Notable translated content from the Mother Ship included Allan R. McDougall’s interview with Stephen Stills, Jonathan Cott’s obituary of Igor Stravinsky, Jann Wenner’s interview with John Lennon, David Felton’s profile of Elton John, Ben Fong-Torres’ profile of the Jackson 5, and Fong-Torres’ obituary of Jim Morrison.

After the magazine was shut down, Aceves, the editor-in-chief, did not stay in the publishing or the counterculture, instead becoming an expert on the Swiss psychiatrist C.G. Jung. Aceves died in 2009.

In his book Refried Elvis: The Rise of the Mexican Counterculture, Eric Zolov explains:

Another casualty of the crackdown was the countercultural magazine Piedra Rodante. Combining often-daring articles on drugs, politics, and the counterculture in Mexico and abroad with translated material from its parent magazine in the United States, Piedra Rodante quickly proved too much for a regime that sought to recontain the rock movement; after eight issues, the magazine was forced to shut down. Claiming a distribution of 50,000, the magazine not only aimed at a national audience but reached Central and South America, Spain, and the “Chicano youth of North America”––indicated as including the borderlands, New York, and Chicago—as well. As editor Manuel Aceves recognized, the survival of such an effort in Mexico “requires an atmosphere of liberty, both in an objective sense and at the level of consciousness,” which he believed the apertura democratica under Echeverría would provide. “We sincerely hope we aren’t mistaken about this sexenio [six-year presidential term],” he wrote in an opening editorial. During the eight issues of its existence, Piedra Rodante consistently tested the boundaries of the political opening offered by the new regime. An advertisement in its last issue provocatively queried, “How much freedom of the press exists in Mexico?” To fill this gap, the magazine offered “Youth’s viewpoint about their own world versus that of adults. Without inhibition, shame, sweat, or reserve, the sole truth about drugs, politics, sex, rock, art ... a new type of journalism. Enlightened journalism. And enlightening ... The first long-haired news journal.” But its bold testing of political and cultural tolerance––one issue boasted “40 pages replete with drugs, sex, pornography, and strong emotions”––proved too much, especially in the context of an antipornography moralizing crusade spearheaded by conservatives. While called to the attention of the ineffectual Qualifying Commission of Magazines and Illustrated Publications (the government censorship bureau for printed matter) in a letter by a member of Congress, the magazine nonetheless met a quicker fate than what would have been the arduous process of bringing the publisher to court under the rules of the commission: facing threats of physical harm, the editor simply ceased publication.

Rolling Stone celebrated its 50th birthday last year, and there has been no small share of adulatory artifacts, including a big exhibition at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, and a two-part documentary on HBO called Stories on the Edge. In neither case was there any mention of Piedra Rodante, at least as far as I can remember. (The HBO doc jumps more or less directly from the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago to the rise of Bruce Springsteen.) The subject also doesn’t seem to come up In Robert Draper’s 1990 tome Rolling Stone Magazine: The Uncensored History, and it also was apparently not mentioned Sticky Fingers: The Life and Times of Jann Wenner, Joe Hagan’s book on Wenner that came out last year (Amazon searches on “Piedra” in the book yield 0 hits).

What follows are a wealth of images from the magazine’s brief run.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

An early Rolling Stone promotion sent every new subscriber a free roach clip!