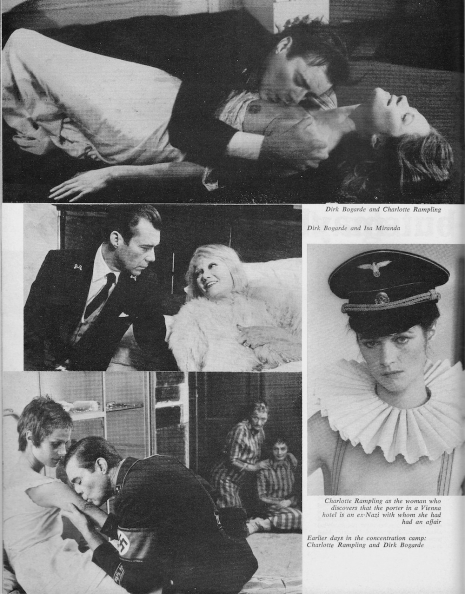

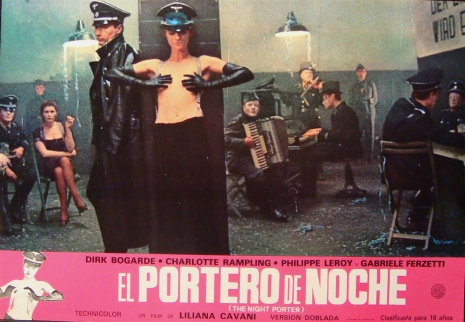

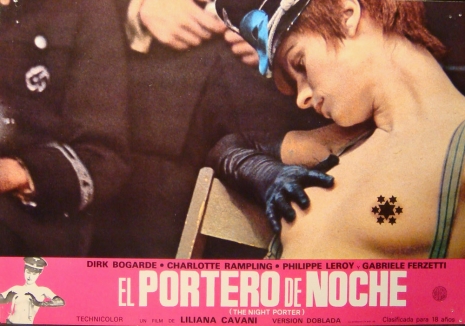

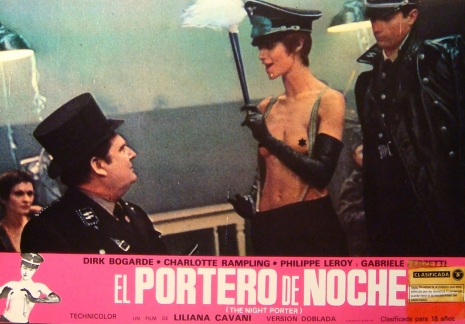

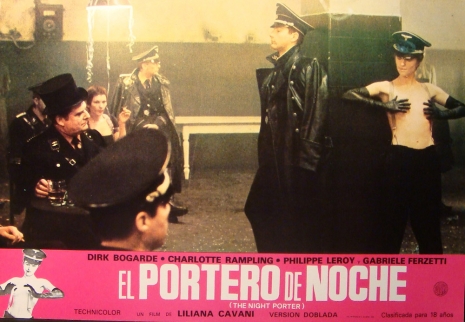

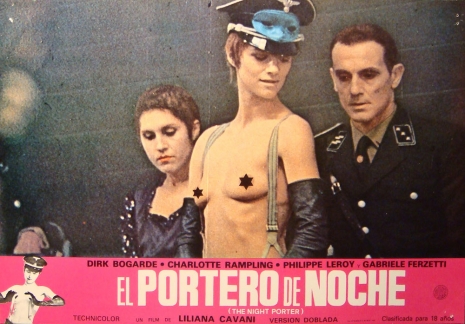

The actor Dirk Bogarde was standing outside the Karl Marx-Hof workers’ apartments in Vienna ready to shoot a scene for Liliana Cavani’s film The Night Porter. Bogarde was playing Maximilian Theo Aldorfer, a Nazi SS officer. who had pursued a sadomasochistic relationship with a concentration camp prisoner called Lucia played by Charlotte Rampling. Bogarde was “shit-scared” wearing a black Nazi uniform in public. He wondered how the local citizens would take to his appearance. He had covered his costume with a raincoat while he waited for his cue. It was almost thirty years since the end of the Second World War when the full horror of the Nazis’ depravity had been revealed.

A large crowd gathered to watch the filming. Bogarde waited for the signal to walk across the cobbled, tram-lined street and enter the apartment. The camera turned-over. Bogarde removed his coat to reveal the SS uniform underneath. On seeing his military outfit, the crowd of onlookers cheered and clapped. They sang the “Horst Wessel Song.” Small children ran towards him just to touch the uniform. The old woman, whose apartment they were using in the film, bent down to kiss Bogarde’s gloved hand and said, “It’s the good days again.” Bogarde felt sick.

During the war, Dirk Bogarde had served as an intelligence officer. He was one of the first officers to enter the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where he witnessed the “mountains of dead people” as he walked through the camp and looked inside the huts where there was “tiers and tiers of rotting people, but some of them who were alive underneath the rot, and were lifting their heads and trying ....to do the victory thing. That was the worst.”

After the war, Bogarde became the pin-up of 1950’s British cinema, most notable for his performance as Simon Sparrow in the highly popular series of Doctor.. movies—starting with Doctor in the House in 1954. But Bogarde never wanted to be a matinee idol. He, therefore, decided on a series of controversial film roles starting with Victim in 1961, where he played a gay barrister, at a time when homosexuality was illegal in Britain, who is blackmailed over a sexual relationship with another man. He followed this up with Joseph Losey’s The Servant, then The Mind Benders, John Schlesinger’s Darling, Losey/Harold Pinter’s Accident, Visconti’s films The Damned and Death in Venice.

It was after the five grueling months of filming Death in Venice when the character of Gustav von Aschenbach had so possessed him, that Bogarde he decided on taking a break from movie-making. He returned to his farmhouse in France with his partner and manager Anthony Forwood, where he spent his time gardening and writing and tending to the 400 olive trees on his land. Time-off was great, but as Forwood pointed out one sunny day, Bogarde needed money to keep his home and lifestyle together. He, therefore, decided to go back to making movies.

Unfortunately, because of his critically acclaimed performances in films like The Servant, The Damned, and Death in Venice, the roles Bogarde was offered tended to be “degenerates,” spies, and Nazis. These scripts began to pile up in his basement.

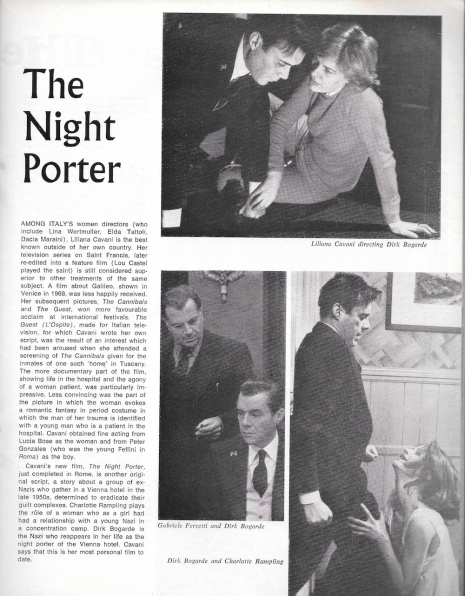

One day, Bogarde was enthralled by a movie about Galileo on television. Though in Italian, he immediately recognized the film as a work of real artistic brilliance and originality. He waited until the end credits rolled so he could find out the name of the director. It was Liliana Cavani. The name was familiar. Cavani had sent him a script which he had deposited in his basement. It was called The Night Porter.

As Bogarde described this script in his biography An Orderly Man:

[T]he first part was fine, the middle a mess, the end a melodramatic mish-mash. Too many characters, too much dialogue, two stories jumbled up together where only one was necessary, but the point was that in the midst of this tumult of pages and words, buried like a nut in chocolate, there was a simple, moving, and exceptionally unusual story; and I liked it.

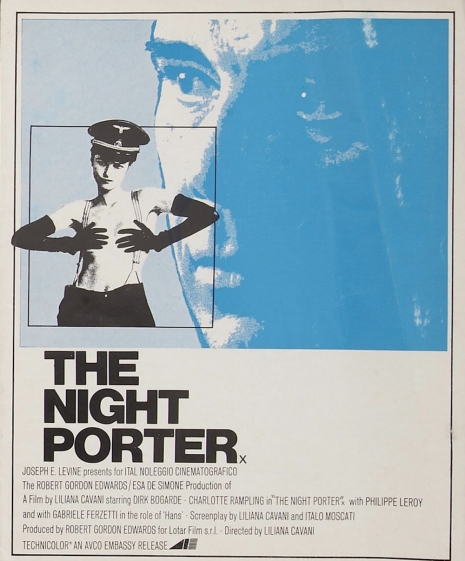

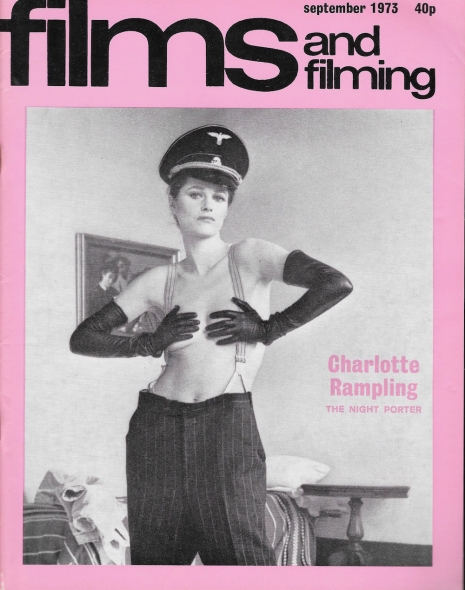

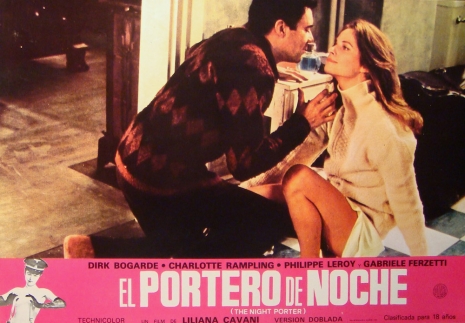

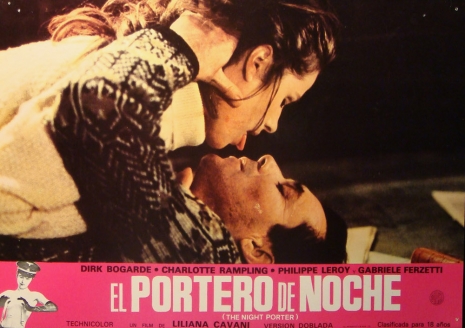

The story was a dark erotic psychological drama centered around the relationship between an SS officer and a young female prisoner, who meet up twelve years after their first encounter inside a concentration camp. In the film, Max is working as a night porter in a German town where the residents are fellow Nazis hiding from prosecution for war crimes. Lucia’s arrival at the hotel rekindles the sexual relationship with Max while threatening the former Nazis with disclosure. The script may have been a “mish-mash” but Bogarde was attracted to the central relationship between Max and Lucia—more so after he found out Cavani had based her script on actual events:

She had been making a documentary for Italian TV on prison camps in, I think, Dachau. Bad weather had forced work to a halt. Sitting under an umbrella in the mud she saw a smartly dressed woman walking through the drenching rain carrying a sheaf of red roses, and she watched as the woman searched among the sites of the long-demolished huts where the prisoners had been held. In time she found the place for which she was looking, the brick angle, flush to the ground, of the hut foundations, and knelt there placing the roses on the spot, and remained, head bowed, in the rain for a few moments, then rose and walked away. With Cavani in pursuit.

She caught up with the woman “who had obviously come to mourn her family” but soon, according to Bogarde, found a far more intriguing story than she had anticipated.

There had been no family. She was not Jewish. She came back, she said, every year on the anniversary of her lover’s death. He was a member of the SS, she was a girl who had been imprisoned for holding Socialist beliefs, and having a well-known Socialist father. The hut foundations, where she placed her roses, were the site of the one in which she had been imprisoned; the day was the anniversary of the day on which her lover had been executed by the liberating Americans. She lived now in America but came back every year on that day. It was perfectly simply told, and unemotional. She left in the rain leaving Cavani with a story which haunted her for months.

What, she thought, would have happened if the SS man had not been killed? Had escaped and gone to ground like so many others, and years later, in some unexpected place, at some unexpected time, the two had met again? What then? She wrote ‘The Night Porter’.

In his authorized biography of Bogarde, John Coldstream wrote:

On Cavani’s own, slightly more prosaic account, she had interviewed for her documentary two Italian women—both partisans, neither Jewish—who had survived the camps. One of them had been in Dachau between the ages of eighteen and twenty-one, and, since the war, had returned every year on her holidays, for reasons she would not—perhaps could not—explain. The other, a bourgeoise from Milan, had found on being freed from Auschwitz that she could not go back to her husband and children because she was treated like a wretch, and made to feel she was an embarrassment, a reminder of something too disturbing. She had experienced cruelty, horror, ordeals—but what she could not forgive was being made by the Nazis to perceive the depths of human nature. She told Cavani: ‘Don’t think that all victims are innocent.’ So the director, troubled by what she had heard, set out to tell a story that took human nature ‘to the limits of credibility’, through a sado-masochistic relationship made possible by the extreme situation in which the principals find themselves. In the same interview, Cavani did not use the word ‘love’. She stated openly that because of the way human nature worked, for her, the basic text in life was de Sade; it should be taught in schools. However, in Dirk’s much publicised view they were to tell a ‘love story’—‘rather like a tiny flower thrusting through the brutality and degradation of a battlefield’. At a different level, the role of Max the porter was one afforded an extraordinary opportunity to exorcise—a cynic might say exercise—demons, at very high risk.

The script was edited down by Cavani then added to and changed by Bogarde, Forwood, and Rampling. The finished film asked more questions than it answered but it proved to be more successful in Europe, where the scars of the Second World War were still very visible, than in America where it was myopically dismissed as “junk,” “vile,” and “depraved.”

H/T Happyotter.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

‘The Mind Benders’: The true story behind the cult classic psychological thriller

Dirk Bogarde still cool

Dirk Bogarde: A Life of Letters

Dirk Bogarde makes a TV ad for sunglasses in Rome, meets Luchino Visconti, 1968

Dirk Bogarde: Never screened on TV interview from 1975