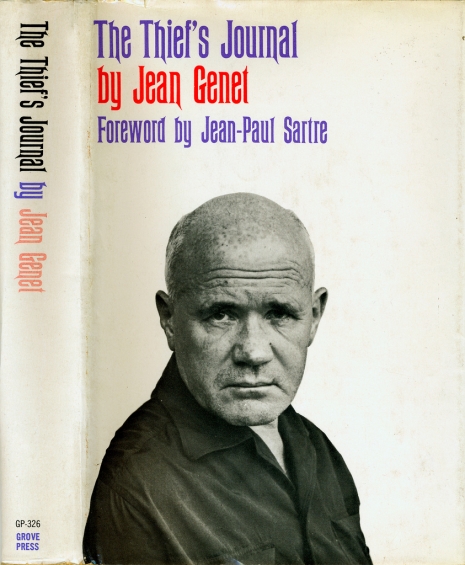

In 1950, the great French criminal, poet, novelist, playwright and homosexual Marxist revolutionary, Jean Genet—one of the towering literary talents of the 20th century—directed his only film, Un chant d’amour (“A Song of Love”), a silent, 26-minute black-and-white short depicting the sexual fantasies of two male prisoners, one young, one older, and a self-loathing prison warden who gets off watching them. In the role of the younger prisoner, Genet cast his then lover, 18-year-old Lucien Sénémaud, who would later leave him for a woman.

Un chant d’amour is one of the earliest classics of queer cinema and the film caused scandal and censorship crackdowns for several years when attempts were made at public screenings. This controversy—and the difficulty of actually seeing the film allowed Genet to put his well-honed conman skills into action as he sold “the only” print to several wealthy porn collectors. Like his books Un chant d’amour kept Genet’s name in the news with near constant censorship battles.

When Jonas Mekas wanted to screen the film in New York, he had to smuggle it past customs officers by hiding the film—cut into several pieces—in his pockets. As Mekas explains in his intro to Cult Epics DVD release of Un chant d’amour, he happened to be seated next to British playwright Harold Pinter who was flying to America for the 1964 Broadway premiere of his play The Homecoming. Pinter’s fame helped him distract a star-struck customs officer as Mekas whistled by.

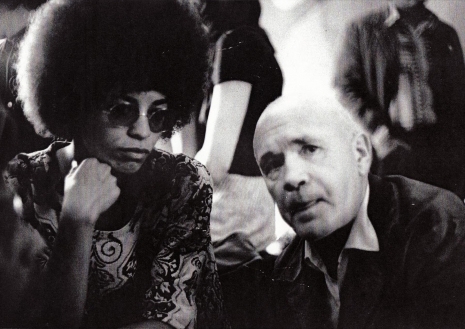

Jean Genet with Angela Davis

From an extensive and thoughtful essay about Un chant d’amour at Jim’s Reviews:

When Mekas screened the picture at the Film-Makers’ Cooperative (which he’d co-founded, as he later would Anthology Film Archives and Film Culture magazine), police burst in, beat Mekas, threw him in jail, and sneered that he should be shot for “dirtying America.” The case was later dropped, since Genet was himself something of a celebrity, with two plays running in New York; but Mekas received a suspended six-month sentence for screening another landmark LGBT film, Jack Smith’s gender-bending Flaming Creatures. Déjà vu: more police raids a few months later in San Francisco when Genet’s film was shown to private groups.

The American Civil Liberties Union brought suit, enlisting the expert testimony of the brilliant critic Susan Sontag, but to no avail. The California District Court of Appeals banned the film, and the decision was upheld by the US Supreme Court.

Unwittingly, Genet had helped narrow the US’s legal definition of obscenity, which had earlier been expanded to include explicit works with “literary or scientific or artistic value.” In the UK, despite a scattering of underground screenings over the years, the film was not even presented to the British Board of Film Classification (i.e., censorship) until 1992. Happily, times have changed – even if it’s taken several decades – and we can now appreciate Genet’s film on its own terms… even if, ultimately, Genet himself could not.

Today, perhaps the most shocking aspect of Un chant d’amour is Genet’s denial of it, beginning around 1975 when he huffily refused a 90,000 franc award from the Minister of Culture, of office which he equated (not unjustly) with censorship: and by the way, hadn’t he made the film a quarter of a century earlier. Edmund White offers some intriguing speculations about Genet’s denunciation: “perhaps because as his sole film it seems a slender accomplishment given his overwhelming lifelong ambitions towards cinema, perhaps it reminded him of a sterile, unhappy period in his life and of his now-dead love for Lucien, or perhaps because it was one more instance of his trafficking between art and pornography in an ambiguous territory he never felt happy about… [And] the extra-artistic reactions to his work – legal, moral, titillated – irritated him. He told Papatakis he didn’t like the film because it was too bucolic and not sufficiently violent. It is also Genet’s last attempt to portray homosexual desire.”

Genet marching with two of his revolutionary queer literary compatriots, Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs at the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago.

If you look at late 60s issues of The Village Voice and other underground newspapers, there were often small ads advertising screenings of Un chant d’amour along with films like Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks or Scorpio Rising (or Andy Milligan’s Vapors, which mostly takes place in a gay bathhouse) at cinemas with names like “The Tomkat Theater” or “The Adonis Lounge.” These film titles were pretty much code words indicating gay cruising scenes, but in a manner likely to fly right over the heads of the NYPD’s vice squad.

Interesting to note that today, Un chant d’amour, this once ultra-controversial, nearly-impossible-to-see banned film—along with Jack Smith’s Flaming Creatures, mentioned above—is today just another YouTube clip.