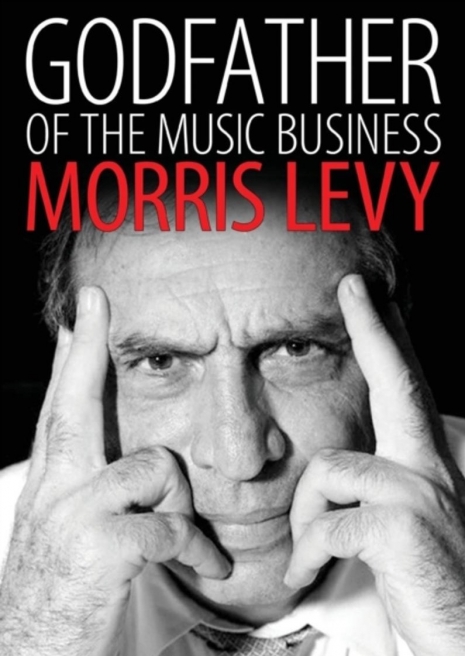

Last April, we told you the story of Richard Goldman, the singer/songwriter who found out that albums of his songs were released without his knowledge or permission. The LPs were issued as part of tax shelter deals, a common practice from 1976-1984. Albums of this sort were ostensibly designed to fail; vinyl collectors later dubbed them “tax scam records.” This article is the first in a two-part examination of the label that set the standard for issuing tax shelter albums. It’s a company that was started by one of the most infamous figures to ever make a buck in the music business.

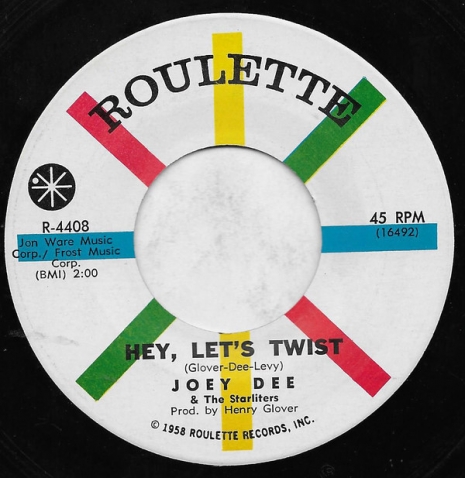

Morris Levy was born in New York City on August 27th, 1927. As a teenager, Levy started working in nightclubs which were controlled by the mob. In 1949, he opened Birdland, a venue that would go on to become one of the most beloved jazz clubs in the world. In 1957, he founded Roulette Records, a label that subsequently issued a number of hit records, including “Peppermint Twist” by Joey Dee and the Starliters, and “Hanky Panky” by Tommy James and the Shondells. Levy learned early on the value of music publishing, and would often add his name to songwriting credits, even though he didn’t have a hand in their creation and had no musical talent.

In his book, Me, the Mob, and the Music, Tommy James says Levy never paid him royalties, despite the fact he had recorded quite a few hits for Roulette. James does concede that he was given artistic freedom, which he wouldn’t have had if he’d signed with another label.

Tommy James and the Shondells, Morris Levy, and a Gold record for “Hanky Panky.”

A number of mafia figures were regular visitors to the Roulette building, including Gaetano “Corky” Vastola, a New Jersey gangster and one of the owners of the label. Tommy James also frequented the company’s office, observing enough to learn why Levy had a reputation for using strong-arm tactics.

It is always reported that there are five major crime families in New York—Gambino, Genovese, Colombo, Lucchese, Bonanno—and that’s mostly true. But back in the sixties, there were six families. All of the above and the Roulette family. It was not for nothing that Morris Levy was called the Godfather of the music business. People from all over the industry called him or came to him to sort out problems. If somebody from Atlantic Records or Kama Sutra found out that their records were being bootlegged, they called Morris.

It seemed like once a month Morris would grab [his associate and bodyguard] Nate McCalla and a few baseball bats, which were in his office, and take off for somewhere in New Jersey or upstate New York. It was a ritual. “KAREN,” he would yell out to his secretary, baseball bat in hand. “Call my lawyer.” And off they would go. (from Me, the Mob, and the Music)

There were a number of subsidiary labels connected to Roulette, including Tiger Lily Records. The company was incorporated in 1976, and released over 60 albums that year. Levy gathered content from seemingly anywhere he could find it, using such cast-offs as demos, outtakes and live recordings for the Tiger Lily LPs. He even reissued a handful of albums that originally came out on the Family Productions record label, which wasn’t affiliated with Roulette. The majority of the artists on Tiger Lily would be unknown to the general public. In my view, this was done, in part, to ensure a plausible deniability if the I.R.S. was to come calling. “Tax scam records” were meant to bomb, giving investors the maximum amount they could deduct on their taxes, while spending as little cash as possible. By putting your money into an artist that showed promise, a case could be made that, ‘Hey, we took a chance, but nobody bought it.’ This also meant that the label looked for artists that exhibited a certain level of talent, resulting in a number of Tiger Lily albums by obscure acts who had exceptional material.

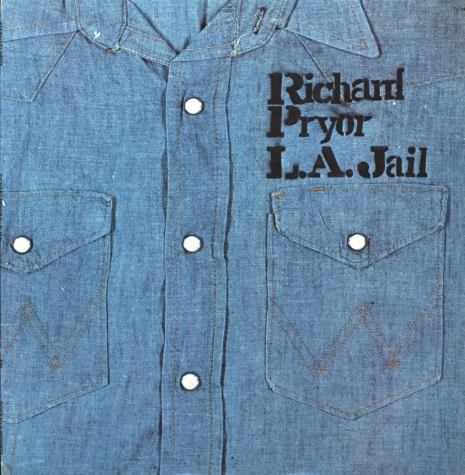

One of the easiest (and cheapest) Tiger Lily albums to acquire is L.A. Jail, a collection of Richard Pryor stand-up recordings. There has been much speculation about whether Pryor authorized this release, and there are a couple of clues that he was, at the very least, aware of the LP’s existence.

In the December 24th, 1977 issue of the influential trade magazine, Billboard, there are three chart listings for Pryor noting that Tiger Lily contributed to sales of his records. This leaves little doubt that Pryor knew about the album. It also implies that L.A. Jail sold well, which is odd, considering how Tiger Lily seems to have had little interest in promoting or circulating copies of their other records.

Another indication of Pryor’s involvement comes via another major publication, Variety, and a Morris Levy interview that appeared in a spring 1978 issue of the magazine. It’s also the most fascinating. Levy’s admission of releasing a Pryor LP for tax shelter purposes provides a rare glimpse into the inner workings of the label.

He [Levy] said he did one tax shelter deal, with Richard Pryor tracks, and made money, adding “I wouldn’t go into a tax shelter deal unless I was in the record business.”

Levy’s reveal that he participated in a tax shelter album is a big deal, mainly because other inferences can be made—namely that Tiger Lily was indeed a cog in a tax shelter operation. There’s no way Levy would’ve told an interviewer this if the Pryor undertaking wasn’t legal, ensuring he did this one by the book. It provides evidence as to why there are so many copies of L.A. Jail still around, as Levy surely pressed up the required legal minimum of 1,000 copies, and probably a lot more than that. It also means the LP was adequately distributed to stores, explaining how it sold enough to garner multiple listings on Billboard charts. Doing one tax shelter record legally with a name act could have been an attempt to legitimize the label, as well. But Levy only admitting to the single release is also telling. Why only bring up just that one Tiger Lily LP, if everything was on the up and up?

Levy worked closely with another company, R.A. Inbows (get it?). This corporation was in the business of buying and licensing master recordings, among other pursuits. They were also involved with tax shelters (read a court document detailing the company’s role in a motion picture tax shelter here). Copyright credits for R.A. Inbows appear on the back cover of every Tiger Lily LP. Their agreement with Tiger Lily likely involved them leasing masters from Levy (despite the copyright notices implying ownership), which they would, in turn, license to investors. These recordings formed the basis for the tax shelter albums on Tiger Lily.

Levy’s other obligations included creating the album package and pressing up records; he would be compensated for this work by investors. Levy was also responsible for placing the albums in stores (Roulette was the distributor for Tiger Lily) and promotion, but other than the Pryor LP, there’s little evidence he did any of that. Conventional wisdom is that Levy unloaded some of the Tiger Lily albums via his record store chain, Strawberries, but that the majority of the label’s stock was simply warehoused and/or destroyed.

While it’s true Tiger Lily issued LPs without the knowledge of the performers featured on the records, that wasn’t always the case. Though we can’t be definite about Pryor, a number of artists have acknowledged that, for various reasons, they willingly made deals with the label.

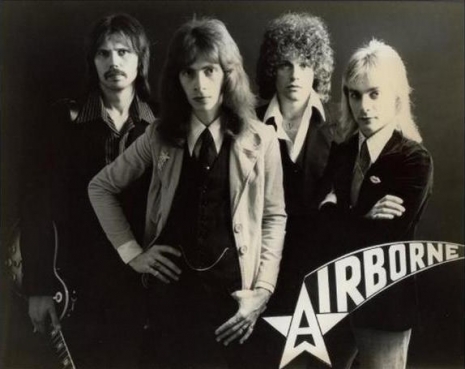

Airborne was formed in 1973 by a group of twenty-somethings who had been classmates at a New Jersey high school. Airborne’s bassist, Barry Fields, was a member of the New York City glam band, Teenage Lust, when they sang back-up for John Lennon during a concert at Madison Square Garden.

Airborne publicity photo. Barry Fields is second from the right.

The band issued two demonstration discs, in the hopes of attracting a record contract, but nothing materialized. After years of trying, Airborne was offered a deal with Tiger Lily. “Our manager/agent in New York was trying to get us a major record deal with a large label,” Barry Fields relayed to me in 2013. “He told us about the Tiger Lily/Morris Levy one record deal, and we all agreed that it might be a good thing to get the attention of a larger label, and that it would open doors for us to play larger venues (which it did).” A contract was signed, and master tapes were sent off to the label, which became their self-titled album. Fields says that they “were presented with a check for a few thousand dollars, which we gladly accepted. Bob [West], our manager, did inform us that this record deal was part of some sort of tax scam; we really didn’t care.”

The Airborne album, largely consisting of melodic pop and glam-inspired rock, is quite good. A couple of the tunes had potential to have been AM radio hits, had the circumstances been different, while a track like “Give Us a Kiss,” a spirited, New York Dolls-inspired number (with a couple of nods to the Beatles), was probably too off-kilter and anachronistic to have swayed another record company to sign them—as great as it is.

Airborne was just one of many promising groups that had a record on Tiger Lily. The band was in the midst of compiling new songs to present to other labels, when their aforementioned manager died suddenly. Though they secured new representation, they never quite got back on track. By the late ‘70s, the band had thrown in the towel. In 1997, Barry Fields co-founded the Father’s House Christian Fellowship church, and ten years later earned a Doctorate of Divinity. Pastor Barry passed away last April at the age of 65.

There’s a digital reissue of Airborne on Amazon, though its legitimacy is suspect.

There are quite a few holes in the Tiger Lily discography, which has left collectors wondering. Was this due to carelessness on the part of the label, or are there TL albums that are so rare they haven’t been discovered yet? An answer appeared around 2014, when Jim Armstrong’s Feels Like Spiders seemingly feel from the sky. After someone spotted the record at UK flea market (and purchased it for just 50p), various queries for the LP began appearing online. One message board posting by an “Uncle Jimmy” seemed to have been written by the man himself. I contacted this person, and, turns out, it was indeed Jim Armstrong.

“I’ve been playing with bands most of my life,” he wrote in an email. “I was recording in P.C.I. Recording Studio in Rochester, NY with a band named Spyders, when someone asked me if I wanted to sell the album to Roulette Records as a tax shelter deal; considering the band had broken up, I accepted.”

Armstrong’s lawyer put together a contract, and the two met with Morris Levy and Fred Balin, producer/A&R at Roulette. In addition to some money, Armstrong was to receive twenty-five copies of Feels Like Spiders. He remembers Levy telling him, “Don’t expect any more money or royalties.”

A copy of Feels Like Spiders recently turned up on eBay. The seller uploaded three audio samples, and it appears that, as of this writing, it’s the only way to stream anything from the LP. The first excerpt, “Penny Pinchin’ Mama,” is the highlight of the bunch, an acid rocker that conjures up the Deviants and Overnite Sensation-era Zappa. Armstrong says the song received a bit of radio airplay in Boston.

Jim Armstrong later become a teacher and a novelist. He still plays music. Check out his post-Spyders band, Naked Lunch, on ReverbNation.

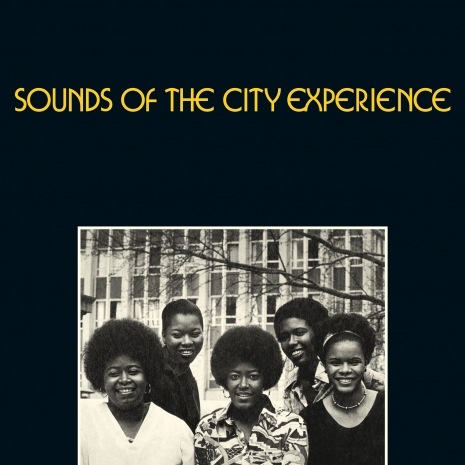

The recordings for the funky Sounds of the City Experience LP were provided by songwriter/musician/producer, Mario Sprouse. “I put together some master tapes from sessions I had done with my band,” Sprouse told me. He did so at the request of a friend of his, Lori Butler, who was a personal manager (she’s now deceased). “Lori mentioned to me that she knew someone who was buying masters for albums. That’s all I knew.” Sprouse felt that a Tiger Lily LP would act as a kind of business card, which would help secure future work. He didn’t have direct contact with anyone from the label, and never even heard of Morris Levy until decades later.

The Sounds of the City formed in New York City in 1963. There were many lineup changes over the ensuing years, with Sprouse among the few mainstays in the group. In 1970, he got a job as the musical director for a college play entitled, Seek and You Shall Find. Three of the Sprouse-penned songs written for the production—utilizing the Sounds of the City as the backing band for the studio recordings—ended up on the Tiger Lily LP. Additional cuts had been previously released on singles, which came out via the group’s own label, including the funktastic, “Keep on Keepin’ On.”

This tune and a couple of others had come out under the name Flypaper, named after another college musical Sprouse had been a part of. The photograph featured on the cover of the Tiger Lily album was originally used to promote Flypaper!, and featured five of the young women in the play.

Mario Sprouse left the Sounds of the City in 1978. Forty years on, he’s still active and involved in a number of projects, including a new musical based on the life of Josephine Baker.

In 2013, Jazzman Records made the Sounds of the City Experience album available once again on LP and CD (with bonus tracks). It’s one of the few Tiger Lily records to receive an authorized reissue.

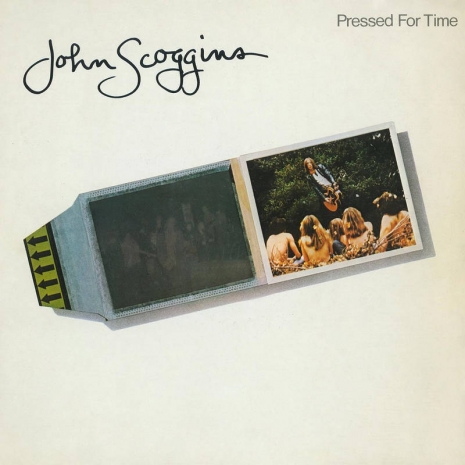

The most high-profile Tiger Lily LP to get the reissue treatment is Pressed for Time, a power pop record by one John Scoggins. The Long Island-based singer/songwriter was the leader of a group called the Ramparts, which had been together in one form or another since the dawn of the seventies. The Ramparts gigged often, performing at Max’s Kansas City and other bars in and around New York City. They played some bigger shows, too, including an arena date opening for Neil Young.

Scoggins had been working part-time as a roadie and a gas station attendant, when the Ramparts were offered a contract with Tiger Lily—over the phone! The label claimed they had heard the Ramparts’s demos at a recording studio.

Pressed for Time is a remarkably solid album, considering it’s a collection of songs that were never intended for release as-is. The record is full of strong, well-played material, with first-rate harmonies. Scoggins’s George Harrison-like vocal leads the way on power pop numbers like “Treat Me Right,” a track so good that, in a just world, it would be played on Classic Rock radio every damn day.

Another standout is “Mr. Questions,” a sublime slice of singer/songwriter pop, with some killer guitar/sax interplay and a closing riff to die for.

The only real misstep on the LP is the goofy “She’s Long, She’s Tall,” a live staple that was recorded despite Scoggins’s objections. The album ends with a cover of the Easybeats’s nugget, “Good Times.” It’s a departure from the overall tone of the record, but that’s okay, because it totally rocks.

As for the cover art, it features an awkward image of Scoggins posing in front of a group of topless female onlookers.

Despite Tiger Lily’s lack of artist support, Scoggins, more than any other performer on the label, took the release of his Tiger Lily album seriously. He actively promoted the record, taking out ads in rock magazines, and mailing copies of his LP to various media outlets (he regularly visited the Tiger Lily office to pick up boxes of Pressed for Time). Scoggins even went to the trouble of correcting the credits, pasting over the faulty information on the back covers, and inserting promotional items (like photos and bios) into the jackets before sending them off.

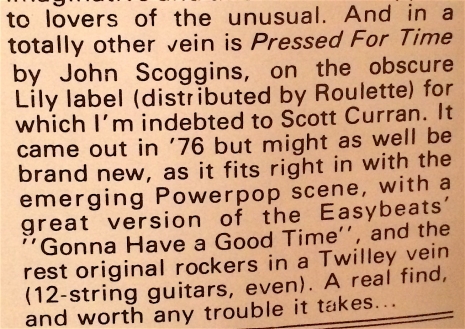

The LP did get manage to get some radio airplay, including spins on the popular New York station, WPLJ. Scoggins also scored an appearance on the long-running New York TV program, The Joe Franklin Show. In addition, the album received some sporadic print coverage. A positive review by Greg Shaw appeared in the November 1977 issue of Bomp! magazine. Shaw references the curious matter that the record, despite being a relatively new release (it came out in December 1976), was already hard to come by.

A 1979 newspaper article on Scoggins noted that he and the Ramparts had just completed an East Coast tour, and that he was in talks concerning the release of his follow-up album, but said record never arrived. Following a 1982 tour of California, Scoggins faded from view.

After years of searching, writer/collector Collin Makamson finally tracked down Scoggins around 2009. The former Tiger Lily signee struck Makamson as an odd duck: “He seemed particularly jittery for an ex-musician when I spoke to him.” Scoggins didn’t want to even reveal where he lived, but did clarify that all of the promotion for the record was done by him, without any support from Tiger Lily. I asked Makamson if Scoggins knew the true purpose of the label. “As for being aware of the scam, he never led on that it was anything illegal, just that the label wasn’t very supportive…so I’m not sure how aware he really was.”

In 1989, Levy sold off Roulette and his collection of various labels, with Rhino Records acquiring the North American rights. In 2010, Rhino put out a digital-only version of Pressed for Time, and last year the label made the LP available again for Record Store Day. Collin Makamson co-wrote the liner notes. Scoggins is said to have been thrilled with the reissue.

There are a few vintage John Scoggins videos on YouTube. They were uploaded by “jessefingers” to promote Rhino’s 2010 re-release of Pressed for Time, though they were edited together in a bizarre, haphazard manner. We’ve embedded the best segment—which features footage of the Ramparts playing songs from Pressed, plus excerpts of Scoggins on The Joe Franklin Show—but it’s still quite rough.

In about a week’s time, we’ll take a look at a few other acts that had albums on Tiger Lily, though these artists were in the dark about it until years later. Their Tiger Lily LPs are now so rare and sought-after that one has sold at auction for five figures. We’ll also recount the downfall of Morris Levy.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

‘Tax Scam Records’: Artist discovers albums of his songs were released by shadowy companies in 1977

‘Almost Famous’: Artist discovers his music was released by shady record companies in 1977 (Part II)

The strange tale of the unauthorized albums of the Beatles Christmas recordings