This is a guest post by Spencer Kansa, author of the Marjorie Cameron biography Wormwood Star, coming out soon in a new edition.

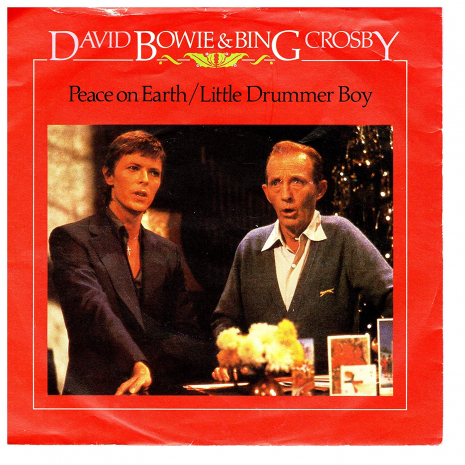

Bing Crosby and David Bowie bookend the 20th century of popular music. Massively influential and innovative in their own individual ways, these master vocalists were bona fide icons of their respective generations, with careers spanning 50 years. Still, few at the time would have believed that their collaboration in 1977, on Crosby’s Merrie Olde Christmas TV show, would become the beloved cultural artifact it is today.

On paper, it seemed an improbable pairing. The easygoing crooner, whose smooth reassuring voice helped shepherd Americans through the Depression and Second World War into peacetime prosperity, singing carols with the premier rock star of the Space Age, who’d risen to become the artistic driving force behind Western popular music. But any lingering doubts were banished that magical moment when Bowie’s cockneyfied croon gels perfectly with Bing’s bass-baritone and they start to sing.

For Crosby, the duet was a marvellous capper on an illustrious career in which he conquered the mediums of radio and television; become an Academy Award-winning actor and one of the biggest box office draws of the 1940s and 50s and, above all, reigned as one of the most successful recording artists in history, with a staggering 41 #1 hits, including “White Christmas,” which remains the world’s best-selling record of all time with over 50 million copies sold.

For Bowie, the duet was another surprising left turn that confirmed his status as the most audacious and uncategorizable pop artist of the 1970s; occurring at a midway point in his imperial period, that had seen him revolutionize how pop music was synthesised and presented on stage, on video, and on a dozen long-playing masterpieces. An astonishing creative streak that would further yield the new wave classics Lodger and Scary Monsters; the pop perfection of Let’s Dance and the global domination gained by its accompanying Serious Moonlight Tour, culminating with his commanding performance at Live Aid in 1985.

But the story behind the duet has generated certain myths over the years, and to iron out a few of them, I recently spoke with Bing’s daughter, the actress Mary Crosby, who, in 1980, rose to international prominence herself playing Kristin Shepard, the conniving, sloe-eyed seductress in the popular soap opera Dallas, and famously fired a couple of slugs into the dastardly J. R. Ewing, in a cliffhanger reveal watched by over 350 million viewers worldwide.

Since they began being broadcast in 1970, Bing Crosby’s Christmas specials had become a televisual tradition: a welcome, perennial presence in American homes. The 1977 episode happened to coincide with Bing’s 50th anniversary in showbiz, and as part of that celebration included concert performances in the UK that autumn, the programme-makers decided to film and set that year’s show in England, casting British entertainers. According to Mary, the idea to invite Bowie onto the show came from one of the producers, whose attitude was: ‘Wouldn’t it be wild?’ “They knew it was a long shot but it was a stroke of genius.” The offer came at an opportune for both singers who were, fortunately, able to synchronise their busy schedules. Bowie was already in England to drum up publicity for his latest single and album, Heroes, which was set to be released on September 23rd and October 14th respectively.

His TV itinerary began on September 7th, when he travelled to Granada Studios in Manchester to sing the title track on the teatime TV show fronted by his old mucker, Marc Bolan. He sang it to a backing track created by Bolan’s studio band, which included previous Bowie alums, Herbie Flowers (on bass) and Tony Newman (on drums), with Bowie himself trying his best to approximate Robert Fripps’s original guitar lines. Although they’d planned to end the show duetting a new song together (“Sitting Next To You”), this was scuppered when Bolan slipped off his monitor and the jobsworth crew refused to shoot another take.

Four days later, Bowie arrived at Elstree Studios in Borehamwood to perform “Heroes” again and “do something” with Bing Crosby.

For Mary Crosby, who performed on the show, alongside her actress mother, Kathryn, and her brothers, Harry and Nathaniel, Bowie’s arrival proved particularly memorable: “My brothers and I were teenagers at the time and Bowie walks in with this woman and they’re both wearing mink coats with full makeup on and red hair – and they matched! It was such an outrageous entrance.” Although she concedes that Bowie’s appearance – especially his Ziggy red hair – might not have been exactly as she remembers it, she’s adamant that he and his female companion – whom she assumed was his wife, although it was most likely Coco Schwab, Bowie’s personal assistant, as Bowie’s marriage to Angie was already in tatters – entered wearing full make-up. “Your memory changes with history, but their entrance was so outrageous. And they cleaned Bowie up for sure. They took off his full make-up. We were tickled; we were stunned. And we thought it was fantastic – and it was!”

One of the great anomalies of the show is the repeated story about how Bowie refused to sing the suggested “The Little Drummer Boy” song because he hated it and threatened to walk unless he was given an alternative number. This is the reason given for why the “Peace on Earth” counterpoint was hastily composed by the show’s writer, Buz Kohan, the composer, Larry Grossman, and the show’s music director, Ian Fraser. And yet, Bowie does actually perform “The Little Drummer Boy” tune; he and Crosby sing the first eight bars together before Bowie launches off into the counter-melody, and Mary Crosby believes this change of heart happened “once they got together. Any resistance there may have been was shifted when they realized they were in good hands with each other. When they went to the piano and started playing, David was nervous and dad was leery, but the moment the song started they both relaxed because it was all about the music.”

Bowie and Bing rehearsed this new arrangement, as well as their playful banter, which played upon their intergenerational differences, for an hour and then recorded the finished song in three takes. According to Kohan, Bing “loved the challenge,” and Mary relates how gracious and accommodating her father was when Bowie asked if they could change the original key to better suit his voice. For whatever reason the counterpoint was created, it proved to be an inspired course of action because it created a dynamic that wouldn’t have existed if they’d just settled on a straightforward singalong of the song. Mary agrees and remembers watching in amazement as the duet took shape: “My brothers and I didn’t know how it would pan out, and we watched as they worked through it on the soundstage, and it made me really happy when it happened. Even at the time, I knew magic was being made. I knew it was an extraordinary moment in time.”

The premise of the TV special sees the Crosby family travelling to England to spend Christmas at the home of their posh, long-lost relative, Sir Percival Crosby; and the show spoofs several characters from the then-popular British period drama, Upstairs, Downstairs, the Downton Abbey (without the budget) of its day. The Scottish comic actor, Stanley Baxter, drags up as Mrs. Bridges, the cook, and Rose the scullery maid, as well as portraying Hudson, the butler, from the original show.

English thesp, Ron Moody, does a turn as Charles Dickens, and Bowie’s Pins Ups cover co-star, Twiggy, duets with Bing on “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas.” Bing then provides a moving introduction to Bowie’s performance of “Heroes”: “Love and loneliness, just as painful and just as beautiful as they ever were. Whether you’re a novelist, a poet or even a songwriter. It’s all in the way you say it.” This version of “Heroes” is the most alluring of all the TV appearances Bowie made at the time, as being an American programme, he was allowed to sing to the actual original track, and he delivers a mesmerising rendition, with some romantic pantomiming thrown in.

Those present recall how the two legends appeared to get on very well during the taping. Kathryn Crosby was taken with how respectful Bowie was around her husband, and Bowie himself was initially very positive about the encounter, recalling, a few years later, how much he enjoyed discussing the roots of American popular music with Crosby; its evolution from spirituals through early blues and jazz and into rock n roll.

The resulting duet highlighted a very productive period in both men’s lives, albeit one marred by grief and tragedy. The day after filming it, Crosby began recording sessions on what would become his final album, Seasons, and also began rehearsals for his two-week, sold-out string of engagements at the London Palladium, starting at the end of that month.

On 16th September, he and Kathryn were interviewed on DJ Pete Murray’s Open House radio show, where he discussed the upcoming TV special and was highly complimentary about its guest star: “I think we’ll see a different kind of David Bowie. There’s no wild makeup or beard or anything. He’s very clean-cut. We sing a duet and he sings a solo. And I think he’s going to be a real fine… a real great contribution to the show.”

PM: “The funny thing is about David Bowie when he first started, it was a number of years ago, he wasn’t unlike Anthony Newley. I don’t know what he sounds like now but…

BC: He sounds great. He sounds wonderful.

PM: But he’s not doing any of the wild stuff with you?

BC: (Laughs) No. In fact, in the little dialogue scene, he reads lines very well; he could be a good actor, I would think.

KC: It’s a wonderful duet that they sing. Bing does “Drummer Boy” and David does a counterpoint, which is just wonderful, “Peace on Earth.”

BC: If we could release it as a record, that would open up a new field for me. If I could get hooked up with David Bowie’s crowd (laughs). I’ll be a big gun.

PM: This week David Bowie, next week Elton John; what about it?

BC: (Laughs)

KC: Demand the world!

BC: That’s it! Right! (Laughs)

And in a message recorded for his UK fan club, Bing was equally effusive: “You may think it strange, David Bowie appearing with an ancient like me, in a programme to celebrate Christmas, because, I guess, David Bowie’s always been known for rock, hard rock, whatever. The fact is he’s one of the best, but in this show, he appears clean-shaven. He and I sing a duet, he sings a solo, we play a little scene, and I think he’s just wonderful, and a very nice young man.”

For Bowie, September 16th took on a far different resonance. As it marked the day when, barely a week after they reunited on television, Marc Bolan was killed in a car crash, just two weeks shy of his 30th birthday. His funeral was held four days later, and Bowie was observed weeping openly. He’d subsequently take financial steps to assist in the upbringing and schooling of Bolan’s nearly two-year-old son, Rolan.

Bing, meanwhile, wrapped his UK tour and travelled to Spain to unwind with a spot of golf. On October 14, he finished a successful round but suffered a seizure and collapsed on his way to the clubhouse. Although he was rushed to hospital, he was pronounced dead on arrival, due to a fatal heart attack, aged 74. Kathryn and the family were back in America when it happened and speaking later to reporters, she tearfully mused: “I can’t think of any better way for a golfer who sings for a living to finish the round. He’s always been a very simple man. I think he is remembered in songs, isn’t he? I think that’s the way it should be.”

When Bing’s special was broadcast in the US, on November 30th, it aired with an introduction from his widow, who hoped viewers would enjoy the show her husband never got to see.

Five days after Crosby’s death, Bowie made a rare appearance on Top of the Pops, where he delivered another live vocal for “Heroes.” However, a Musicians Union diktat at the time meant artists could only sing along to their original recordings if the musicians on that record were also present in the studio, and so another ad hoc backing track was created featuring Low guitarist Ricky Gardner and Sean Mayes on keyboards (who would join Bowie’s band for the Isolar II World Tour the following year). Tony Visconti supplied bass and recorded the resulting track at his Good Earth studio in Soho. Robbed of Eno’s atmospherics and Fripp’s soaring guitar drone, however, this rather muted version lacked the triumphant power and majesty of the original, which may help explain why Bowie’s greatest anthem was only a minor UK hit at the time of its release.

For five years the Bowie-Crosby collaboration remained unavailable except on bootlegs, until 1982, when RCA released it as a Christmas single. Although Bowie didn’t sanction the release, believing it little more than a novelty, the public had the final say and it reached no. 3 in the UK charts, becoming his biggest-selling single to date.

For a while, at least, its success sat well with Bowie’s mid-80s stature as an all-round entertainer, a man who no longer wanted to be viewed as “an information bureau with red hair.” But when the song re-emerged in the early 90s, after receiving repeated airplay on American radio and heavy rotation on MTV, he appeared genuinely flummoxed by its enduring appeal. Whenever the subject was raised in interviews, he would often downplay its significance and engage in some self-serving revisionism, such as claiming there had been little or no communication between him and Crosby while it was being made. He further alleged that Crosby didn’t know who he was and couldn’t remember his name (in the playful preamble to the duet, Bing pronounces Bowie’s name using the Americanised “Boo-ie” after Jim Bowie, the famous frontiersman, whose hunting knife inspired Bowie’s stage name) and that neither of them were really “present” at the time: Bing due to dotage; Bowie via drugs (which contradicts the official line that Bowie cleaned up his cocaine habit during his residency in Berlin).

In fact, as the footage attests, neither men look particularly out of it at all. Bowie would also draw on the experience for comedic effect, like in 1997, when he told Conan O’Brien “(Bing) just loved the whole Heroes period. He tried for months to get Eno to work with him on his next album.”

Perhaps part of the reason for Bowie being so uncharacteristically ungallant was that, in the 90s, he was overly concerned with re-establishing himself on the cutting edge of popular music, and crooning with Der Bingle didn’t jive with his ‘Avatar of Art-Rock’ status. But in a 1999 interview, with Q magazine’s David Quantick, Bowie was particularly uncharitable: “I think the thing with Bing is the most ludicrous… it’s wonderful to watch. We were totally out of touch with each other.”

DQ: Can you remember what you were thinking when you did it?

DB: “Yes. I was wondering if he was still alive. He was just… not there. He was not there at all. He had the words in front of him. (Deep Bing voice) ‘Hi, Dave, nice to see ya here…’ He looked like a little old orange sitting on a stool. It was the most bizarre experience. I didn’t know anything about him. I just knew my mother liked him. Maybe I would have known (sings) “When the mooooon…’ No… (hums) ‘Dada da, da dada, someone waits for me …’”

DQ: What about “White Christmas”?

DB: “Oh yeah, of course. I forgot about that. (Kenneth Williams voice) ‘That was his big one, wasn’t it?’”

But Bowieologist, Kevin Cann, believes such statements have more to do with Bowie’s habit of feeding an interviewer lines they want to hear rather than any genuine sentiment: “Bowie was often a journalist-pleaser and he kind of fell into Quantick’s trap, who sadly decided to belittle that recording. I’ve absolutely no doubt that Bowie would not have said those slightly derogatory things about Crosby had Quantick not put the whole collaboration down. Overall David had a high regard for Bing, having been brought up with him pretty much on radio and on film. Evidently, his mother was a big fan and she would often take David to see his latest film when he was a kid. I remember he told the producers of the Christmas special that one of the reasons for doing it was to impress his mother, but David was also very astute. Crosby was a giant in his day and David wouldn’t have agreed to appear on the show just to please his mum or to promote a single. I’m sure David had nothing but great respect for Bing as an artist and understood more than anyone how important he was in the history of the business.”

In that same Q interview, Bowie also maintained that his collaboration with Crosby helped pave the way for the I’ve Got You Under My Skin” duet Frank Sinatra sang with Bono on his own Duets album in 1993. Although one could argue that that precedent had already been set back in 1960 when Sinatra welcomed Elvis home from his army service in Germany with a duet on his TV show. But their performance was mostly played for yucks, with the duo comically aping each other’s style and trading two of their signature songs (“Love Me Tender” and “Witchcraft”).

The fact that they performed together at all was surprising considering, just three years earlier, Sinatra infamously disparaged rock n roll as the “most brutal, ugly, desperate, vicious form of expression it has been my misfortune to hear.” Adding: “It fosters almost totally negative and destructive reactions in young people. It smells phony and false.”

He followed this up by making what was widely seen as a thinly-veiled attack on Elvis himself: “It is sung, played and written for the most part by cretinous goons and by means of its almost imbecilic reiterations and sly, lewd – in plain fact dirty – lyrics, and as I said before, it manages to be the martial music of every sideburned delinquent on the face of the earth. This rancid smelling aphrodisiac I deplore.”

In a respectful rebuttal, the Memphis Flash counter-argued: “(Sinatra) has a right to his opinion, but I can’t see him knocking my music for no good reason. I admire him as a performer and an actor, but I think he’s badly mistaken about this. If I remember correctly he was also part of a trend. I don’t see how he can call the youth of today immoral and delinquent. It’s the greatest music ever, and it will continue to be so. I like it, and I’m sure many other persons feel the same way. I also admit it’s the only thing I can do.”

Despite his subsequent musical detente with Elvis, Sinatra’s aversion to rock ‘n’ roll continued into the 1970s, where there are stories of him berating Ahmet Ertegun, founder and head of Atlantic Records, at a party, for inflicting Led Zeppelin on his eardrums. And yet Harry Maslin, Bowie’s co-producer on 1976’s Station to Station, claims Sinatra visited Bowie at Cherokee Studios while they recorded that album, and was so knocked out by Bowie’s version of “Wild is the Wind,” the two men bonded over dinner together. By the early 80s, Sinatra was even warming to the idea of Bowie portraying him in an upcoming biopic, something Bowie had been pitching, publicly, since 1975. And though that never panned out, Sinatra finally reached an accord with rock in the 90s, mainly through partying with Dylan and Springsteen and, eventually, Bono, which is how their duet came about. But, as Mary Crosby rightly points out, “Back then dad and David did it in the flesh, not in separate studios.”

Sinatra’s musical narrow-mindedness could never swing with Bing, who’d actually sung the praises of rock ‘n’ roll on the Cole Porter-penned number “Now You Has Jazz,” in the 1956 film High Society (one of the first times that term was mentioned in a motion picture). “Dad was willing and open to sing anything with anyone,” Mary asserts. “When people were still poo-pooing The Beatles he did the album Hey Jude/Hey Bing. He was open to all the above.”

The bandleader, Artie Shaw, once memorably described Crosby as “the first hip white person born in the United States,” and during his successful salad days, Bing certainly revelled in the hedonism that came with being a popular multimedia entertainer. He considered his biggest musical influence, Louis Armstrong, as “The beginning and the end of music in America,” and it was “Reverend Satchel Mouth” – as Bing fondly referred to him – who originally turned him onto marijuana, and his use of the herb (back when it was still legal) deepened his appreciation of music and helped shape his mellifluous phrasing. In one of his final interviews, Crosby even advocated for its legalization.

SK: People forget how cool your dad was; he helped popularize jazz.

MC: Yes, dad was a huge part of that; he helped create it. He was so involved with jazz. He would finish his radio show and go and see Louis. He knew all the players. He wasn’t limited to any one style. Like the duet with Bowie, it was all about the music.

SK: Isn’t it a shame there’s no footage of your dad and Bowie working through the song?

MC: I know, but there were no outtakes. I think they were both private men and dad wouldn’t have been on board with people seeing that. It went well and they had a great time but then David was on his way; other scenes had to be done.

Although clips of the Bowie-Bing collaboration only currently total around ten million combined views on YouTube (where it’s noticeably devoid of the snark and bile you usually find in the comments section), this is only because previously posted clips, with tens of millions of views each, have been taken down over the years. And millions more have watched the duet across other social media platforms, where it tends to get reposted, especially this time of year. The festive favourite features on the new compilation Bing at Christmas: Bing Crosby & the London Symphony Orchestra (Decca Records). And the album is produced by Nick Patrick, who has pedigree when it comes to such projects, having previously married the music of Elvis, Roy Orbison and The Beach Boys with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra to great success. This time around, Crosby’s Christmas classics have been digitally remastered and enhanced with fresh orchestral arrangements courtesy of the prestigious LSO (London Symphonic Orchestra), and the Crosby family are pleased as Christmas punch with the recording: “Dad’s voice is crystal clear; it sounds more like him than ever,” his daughter enthuses. “White Christmas” is also featured, of course, and this year marks its 80th anniversary. Bing’s signature tune served as a stirring anthem for American troops during World War II, and the Crosby Estate recently shared examples of correspondence between him and some of the servicemen he entertained abroad, as well as poignant letters he sent and received from their families back home. It says a great deal about the man that Crosby kept this mail secret, even from his loved ones, until it was discovered decades later by his widow, locked and squirrelled away in a corner of an attic.

Bing Crosby sings “White Christmas” with Marjorie Reynolds from the movie ‘Holiday Inn.’

SK: In one of your father’s biographies, it’s asserted that the duet with Bowie helped bridge and heal the generation gap that opened up in the late 60s, especially the intergenerational opposition to the Vietnam War.

MC: Well, music crosses all borders, backgrounds and ages, and dad was an equal opportunity player. It’s what separated him from the pack. He was flexible; he would sing with anybody. He thought David was wonderful, and they were both very happy with the result.”

It just wouldn’t be Christmas without them.

Bing at Christmas: Bing Crosby & the London Symphony Orchestra (Decca Records) is out now and is available to purchase at Amazon

This has been a guest post by Spencer Kansa. A new, updated, bumper edition of Wormwood Star, his biography of Marjorie Cameron, will be published imminently and will be available to purchase wherever books are sold.