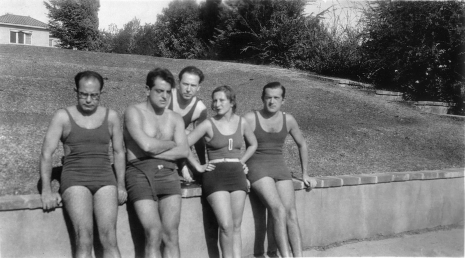

Eduardo Ugarte, Luis Buñuel, Jose Lopez Rubio, Leonor and Tono at Charlie Chaplin’s house, 1930

Whenever someone voices alarm about the “war on Christmas,” I think of my hero, Luis Buñuel, and smile. In 1930, Buñuel disrupted a Christmas party in Los Angeles by leading an attack on the tree and, when it proved hard to destroy, jumping up and down on the presents. Among the guests was Charlie Chaplin, whose house Buñuel often visited “to play tennis, swim, or use the sauna”; sometimes, he sat by the pool drinking with Sergei Eisenstein.

I seem to remember Buñuel or his son, Juan Luis, saying somewhere or other that Buñuel and his comrades attacked the Christmas tree because they found both it and the custom of gift-giving intolerably bourgeois. In My Last Sigh, however, the director writes that he was offended by a patriotic gesture.

He and his roommate, the screenwriter Eduardo Ugarte, were at the house of the Spanish comedian Tono and his wife Leonor, who had been Buñuel’s companions on the recent voyage from Le Havre to Hollywood:

At Christmastime, Tono and his wife gave a dinner party for a dozen Spanish actors and screenwriters, as well as Chaplin and Georgia Hale. We all brought a present that was supposed to have cost somewhere between twenty and thirty dollars, hung them on the tree, and began drinking. (Despite Prohibition, there was, of course, no shortage of alcohol.) Rivelles, a well-known actor at that time, recited a grandiloquent Spanish poem by Marquina, to the glory of the soldiers in Flanders. Like all patriotic displays, it made me nauseous.

“Listen,” I whispered to Ugarte and an actor named Peña at the dinner table, “when I blow my nose, that’s the signal to get up. Just follow me and we’ll take that ridiculous tree to pieces!”

Which is exactly what we did, although it’s not easy to dismember a Christmas tree. In fact, we got a great many scratches for some rather pathetic results, so we resigned ourselves to throwing the presents on the floor and stomping on them. The room was absolutely silent; everyone stared at us, openmouthed.

“Luis,” Tono’s wife finally said. “That was unforgivable.”

“On the contrary,” I replied. “It wasn’t unforgivable at all. It was subversive.”

The following morning dawned with a delicious coincidence, an article in the paper about a man in Berlin who tried to take apart a Christmas tree in the middle of the midnight Mass.

On New Year’s Eve, Chaplin—a forgiving man—once again invited us to his house, where we found another tree decorated with brand-new presents. Before we sat down to eat, he took me aside.

“Since you’re so fond of tearing up trees, Buñuel,” he said to me, “why don’t you get it over with now, so we won’t be disturbed during dinner?”

I replied that I really had nothing against trees, but that I couldn’t stand the kind of ostentatious patriotism I’d heard that evening.

Below, the French TV series Cinéastes de notre temps catches up with Luis Buñuel in ‘63 or ‘64.