I was in a record store the other day when I noticed an LP I’d never seen before—a sealed copy of a 1977 album called William Shatner Live with a $25 asking price. We’ve all heard about Shatner’s sublime 1967 album The Transformed Man, of course, but this record was another animal altogether. For one thing, it’s “a talking album only,” to quote the disclaimer on Elvis Presley’s 1974 album Having Fun with Elvis on Stage.

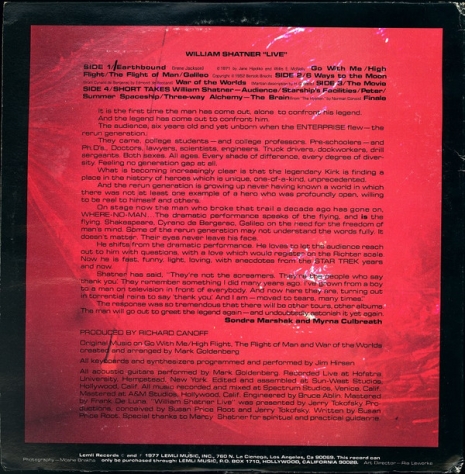

One of the hilarious things about William Shatner Live is the back cover, which has some of the most over-the-top liner notes I’ve ever seen. Here it is:

The overwrought, hyperbolic text is credited to Sondra Marshak and Myrna Culbreath:

It is the first time the man has come out, alone to confront his legend.

And the legend has come out to confront him.

The audience, six years old and yet unborn when the ENTERPRISE flew—the rerun generation.

They came, college students—and college professors. Pre-schoolers—and Ph.D’s. Doctors, lawyers, scientists, engineers. Truck drivers, dockworkers, drill sergeants. Both sexes. All ages. Every shade of difference, every degree of diversity. Feeling no generation gap at all.

What is becoming increasingly clear is that the legendary Kirk is finding a place in the history of heroes which is unique, one-of-a-kind, unprecedented.

And the rerun generation is growing up never having known a world in which there was not at least one example of a hero who was profoundly open, willing to be real to himself and others.

On stage now the man who broke that trail a decade ago has gone on, WHERE-NO-MAN… The dramatic performance speaks of the flying, and is the flying. Shakespeare, Cyrano de Bergerac, Galileo on the need for the freedom of man’s mind. Some of the rerun generation may not understand the words fully. It doesn’t matter. Their eyes never leave his face.

He shifts from the dramatic performance. He loves to let the audience reach out to him with questions, with a love which would register on the Richter scale. Now he is fast, funny, light, loving, with anecdotes from the STAR TREK years and now.

Shatner has said, “They’re not the screamers. They’re the people who say ‘thank you.’ They remember something I did many years ago. I’ve grown from a boy to a man on television in front of everybody. And now here they are, turning out in torrential rains to say ‘thank you.’ And I am—moved to tears, many times.”

The response was so tremendous that there will be other tours, other albums. The man will go out to greet the legend again—and undoubtedly astonish it yet again.

Recorded at Hofstra University in Hempstead, New York, William Shatner Live recalls a time when Shatner’s status as a universally beloved icon of movies and TV was considerably more in doubt than it is today. The original Star Trek series had been cancelled eight years earlier, in 1969, and the 1970s were proving to be a bit rocky for Shatner. Star Trek: The Motion Picture was still two years off, and T. J. Hooker was fully five years into the future. The Priceline ads were two decades away.

Three years earlier, Shatner had appeared in Roger Corman’s Big Bad Mama, and while we’d all think it cool to have a Corman movie on our résumés, appearing in one is probably not a sign that one’s career is heading in the right direction unless it’s your film debut. In 1976 Mark Goodman wanted Shatner to host Family Feud—true story—and Shatner’s most notable acting credit of 1977, the same year William Shatner Live was released, was the tarantula horror movie Kingdom of the Spiders.

Given these facts, William Shatner Live comes to seem like nothing so much as an extended audition reel to send to Hollywood casting agents, as the former and future Captain James T. Kirk shows off his acting skills, reading monologues by the likes of H.G. Wells and Edmond de Rostand, as well as a less expected author: noted Marxist playwright Bertolt Brecht.

To hear Shatner essay the lofty and bracing registers of Brecht’s Life of Galileo is to ponder whether his signature declamatory style is a self-fashioned Verfremdungseffekt, or what we would call an alienation effect.

While the 17th-century scientist Galileo seems an odd choice for the originator of the space-traveling Kirk role, it makes a bit more sense when you realize that Galileo, as the astronomer par excellence, has reason to discuss the celestial bodies of outer space and the possibilities of the human mind. Indeed, it’s probably the most Roddenberry-ish thing Brecht ever wrote.

For those who want to read along, a similar (not identical) translation of the monologue can be found here.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

‘Having Fun with Elvis on Stage’: All banter, no songs, this is the weirdest Elvis album ever

The (very short) true story of William Shatner’s ‘The Transformed Man’ album