The ending to B. S. Johnson’s film Fat Man on a Beach proved rather prophetic, as the author walked fully clothed into the sea, until he disappeared. It was the last sequence filmed for his documentary, and recalls the opening scene to the BBC comedy The Fall and Rise of Reginald Perrin, and, more significantly, Stevie Smith’s poem “Not Waving but Drowning”. Three weeks after filming this scene, in 1973, B. S. Johnson killed himself.

I’ve liked Johnson since I first read him as a teenager, and he is one of the many authors whose books I still return to all these years later. Although I like his work there is something about Johnson that reminds me of the well-kent story of Laurence Olivier and Dustin Hoffman during the making of Marathon Man, where each actor approached their role through their own discipline. Olivier had learnt his technique from treading the boards and performing Shakespeare alongside John Gielgud; Hoffman was a different breed, his muse was Method Acting, where motivation is key. When Hoffman’s character was supposed to have been without sleep, Hoffman decided to stay up all night in order to perform the scene. When Olivier heard the length to which Hoffman had gone to interpret his role, the aging Lord, said, “Have you tried acting, dear boy?”

There was something of the Hoffman in Johnson, or at least, in the shared need to have the experience before creating from it. What Johnson did not do was write fiction - or so he claimed. He saw stories as lies, citing the term “telling stories” as a childish euphemism for telling lies. Johnson did not believe in telling lies, he believed in telling the truth. And it was this that would ultimately destroy him. For once one has abandoned imagination, there is no possibility of escape, or creative freedom.

In 1965, Johnson wrote a play called You’re Human Like the Rest of Them - a grim, unrelenting drama, later made into an award-winning short film in 1967. In it, the central character Haakon realizes his own mortality and the inevitability of death.

We rot and there’s nothing that can stop it / Can’t you feel the shaking horror of that? / You just can’t ignore these things, you just can’t!

For Haakon, and so for Johnson, from “the moment of birth we decay and die.” An obvious proposition, as Jonathan Coe, pointed out in his excellent biography on Johnson Like a Fiery Elephant, one which any audience would have understood before watching. Not so for Johnson the realist - death is the final answer to life’s question, and once realized nothing else is of significance. You can see where this is heading, and how Johnson started to unravel. Though he did go on to write three of his greatest novels after this: Trawl, about life on a fishing vessel; The Unfortunates the episodic tale of a friend’s death from cancer; and the brutally comic Christie Malry’s Own Double Entry, in which the titular hero becomes a mass murderer and succumbs to a sudden death form cancer; you can see the pattern, all three were shadowed with death. However, each is so brilliantly and engagingly written their dark heart is often overlooked.

There is a key moment in Fat Man on a Beach, when Johnson described a motorcycle accident in which the cyclist was diced by a barbed-wire fence, like “a cheese-cutter through cheese.” He explained the story as a “metaphor for the way the human condition seems to treat humankind,” then digressed and said, life is:

“...really all chaos…I cannot prove it as chaos any more than anyone else can prove there is a pattern, or there is some sort of deity, but even if it is all chaos, then let’s celebrate chaos. Let’s celebrate the accidental. Does that make us any the worse off? Are we any the worse off? There is still love; there is still humor.”

This in essence is what is so marvelous about Johnson and Fat Man on a Beach, as Jonathan Coe later wrote as an introduction to the film:

One evening late in 1974, the TV listings announced that a documentary about Porth Ceiriad was to be broadcast. It was being shown past my bedtime (I was 13), but was clearly not to be missed. After News at Ten, we settled down to watch en famille.

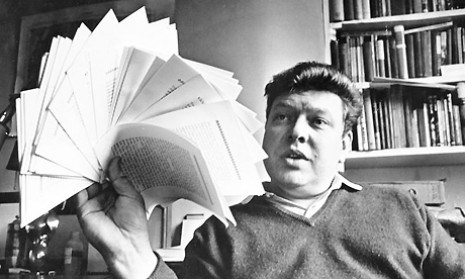

Instead of a tourist’s-eye view of local beauty spots, what we saw that evening was baffling. A corpulent yet athletic-looking man, bearing some resemblance to an overweight Max Bygraves, ran up and down the beach for 40 minutes gesticulating, expostulating, reciting strange poetry and chattering away about the randomness of human life, his quasi-mystical feelings about the area and, most passionately, the dishonesty of most modern fiction and film-making. With disarming bluntness, the programme was called Fat Man on a Beach. We could not make head or tail of it.

And yet memories of this film, so unlike anything seen on television before or since, stayed with me, and 10 years later, when I was a post-graduate student, I stumbled upon a reissued paperback novel by someone called B. S. Johnson and realised that this was the same person. Amazingly, it came with a puff from Samuel Beckett, someone not known as a regular provider of jacket quotations. Encouraged by this, I bought the novel, which was called Christie Malry’s Own Double Entry, devoured it in a matter of hours (it’s less than 30,000 words long) and realised that I had found a new hero.

When I thought about the film that we had watched in a daze of collective bewilderment all those years before, I remembered the sense of fierce engagement, combined with a spirit of childish fun, that had characterised BS Johnson’s virtuoso monologue to camera. I remembered his strange, unwieldy grace - the sort of fleet-footed grace you find unexpectedly in a bulky comedian such as John Goodman or Oliver Hardy. And I remembered the wounded eyes that stared at you almost aggressively, as if in silent accusation of some nameless hurt. It was impossible not to recognise the pain behind those eyes. Even so, I had not realised at the time that I had been looking at a dead man.

The writer David Quantick has uploaded this and some other excellent films by Johnson onto You Tube, which I hope will provide a stimulus to reading his exceptional books.

Previously on DM

More form ‘Fat on a Beach’ after the jump…