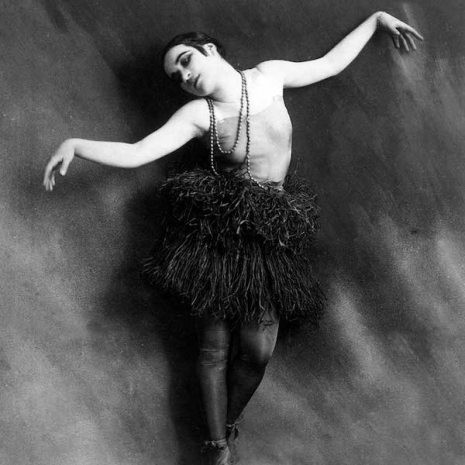

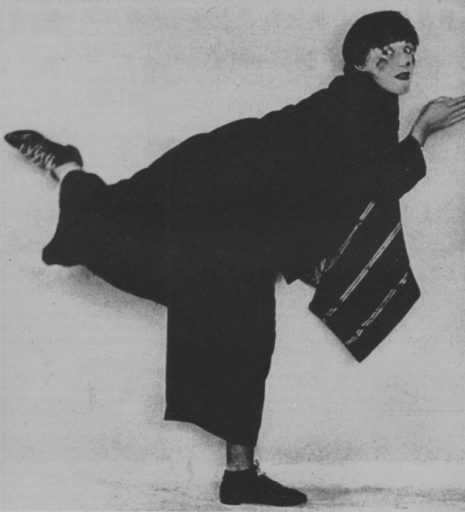

One evening at a local fleapit in Germany, sometime in the 1920s, a young woman stood on stage while the projectionist changed reels between movies and performed her latest dance called Pause. The woman was Valeska Gert who was well-known for her wild, unpredictable, highly controversial, beautiful yet often grotesque performances. The audience waited expectantly, a few coughs, a few giggles, but Gert did not move. She stood motionless in a slightly contrived awkward position and stared off into the distance. The audience grew restless. What the fuck was going on? The lights dimmed, the performance ended, and the movie came on. This wasn’t just dance, this was anti-dance. This was performance art. And nobody knew what to make of it.

Nijinsky had tried something similar a few years earlier, when he sat on the stage to a small audience and said something like: “And now I dance for you the meaning of the War.” He ended up in the booby-hatch. Gert thankfully didn’t. She just antagonized the bourgeoisie and inspired a whole new way of performance.

Valeska Gert was born Gertrud Valesca Samosch in Berlin, on January 11th, 1892. Her father was a highly successful businessman and a respected member of the Jewish community. According to her autobiographies (she wrote four of them), Gert was rebellious from the get-go. She showed little interest in school preferring to express herself through art and dance. At the age of nine, Gert was signed-up for ballet school where she exhibited considerable proficiency but a wilful subversiveness. She hated bourgeois conventions and considered traditional dance limiting and oppressive. But she was smart enough and talented enough to learn the moves and impress her teachers.

On the recommendation of one teacher, Gert was given an introduction to the renowned and highly respected dancer and choreographer Rita Sacchetto. Good ole Sacchetto thought she had a future prima ballerina on her hands and gave Gert the opportunity to perform her own dance in one of her shows. Instead of something traditional, Gert burst on stage “like a bomb” in an outrageous orange silk costume. Then rather than perform the dance as rehearsed and as expected Gert proceeded to jump, swing, stomp, grimace, and dance like “a spark in a powder keg.” Sacchetto was not pleased but the audience went wild. This became Gert’s first major performance Tanz in Orange (Dance in Orange) in 1916.

As the First World War had a dramatic and negative effect on her father’s business, Gert, buoyed by her success with Tanz in Orange, sought out her own career as a dancer, performer, and actor. She worked with various theater groups and cabarets, winning garlands for her performances in Oskar Kokoschka’s Hiob (1918), Ernst Toller’s Transformation (1919), and a revival of Frank Wedekind’s Franziska (1920).

But Gert became more interested in merging acting with dance and performance with politics. She created a series of lowlife characters who she brought to life through exaggerated performance. Or as Gert put it:

I danced all of the people that the upright citizen despised: whores, pimps, depraved souls—the ones who slipped through the cracks.

Long before Madonna caused outrage by flicking-off on stage, Gert was simulating masturbation, coition, and orgasm. It brought her a visit for the cops on grounds of obscenity. Her most notorious performance was the prostitute Canaille. As the academic Alexandra Kolb wrote in her thesis ‘There was never anythin’ like this!!!’ Valeska Gert’s Performances in the Context of Weimar Culture:

Gert’s portrayal of this figure is significant at a time when German state regulation of prostitution, which involved the supervision of sex-workers by the Sittenpolizei (moral police) and severe limitations on their freedom, became increasingly attacked as incompatible with the new democratic system and moves towards greater legal and civil rights for women. The regulation policy was in fact abolished in 1927.

Gert’s unvarnished and ruthless depiction of the prostitute renounced any idealisation. Everyday life—and misery—were reinstated over and above the aestheticised life previously represented in much dance, in particular classical ballet with its fairy-tale plots and noble, dignified representation of humanity.

~ Snip! ~

...Gert did not simply interpret this role as a critique of capitalist society and its treatment of woman as a will-less and submissive commodity. Rather, she strove to depict the female experience in a somewhat autonomous light, with the prostitute enjoying considerable control over her sexuality.

Forget The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, this was a nice Jewish girl ripping-up the text book and changing society. Gert was making a one-woman stand for “those marginalised or excluded from bourgeois society.”

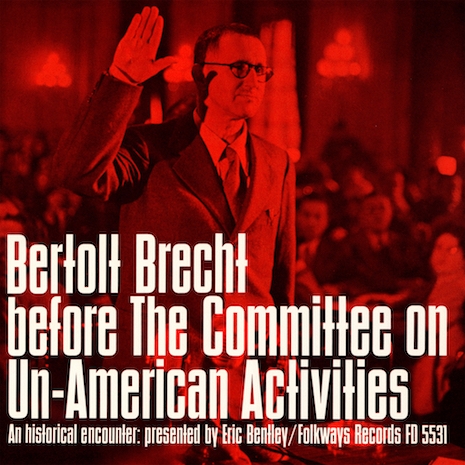

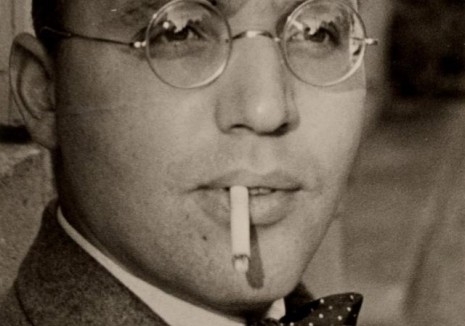

Nothing was taboo for Gert. Her performances covered a wide range of subjects, themes, and characters—from sport to news, sex to death, and to the invidious nature of capitalist society. When Gert asked Bertolt Brecht what he meant by “epic theater,” the playwright replied. “It’s what you do.”

Her reputation grew in the 1920s. She appeared in cabaret, in movies, and in theater productions. Gert would have been a superstar had not the rise of the anti-semitic Nazis brought her career to a premature hiatus. She quit Germany, moved to England, and got married. She then moved to New York, ran a cabaret where both Julian Beck and Jackson Pollock worked for her, and became friends with Tennessee Williams.

After the Second World War, Gert returned to Europe. She tried her hand at cabaret again and found herself cast in movies by Fellini, Fassbinder, and Wim Wenders. But it really wasn’t until the 1970s and the explosion of punk that Gert was fully rediscovered and embraced by a younger generation. Gert was hailed as a progenitor of punk, the woman who “laid the foundations and paved the way for the punk movement.”

Gert died sometime in March 1978. The official date is March 18th. But Gert’s body had lain undiscovered for a few days—something she predicted in her 1968 autobiography Ich bin eine Hexe (I am a Witch):

Only the kitty will be with me. When I’m dead, I can’t feed him anymore. He’s hungry. In desperation he nibbles at me. I stink. Kitty’s a gourmet, he doesn’t like me anymore. He meows loudly with hunger until the neighbours notice and break down the door.

More pix of Gert and a video, after the jump…